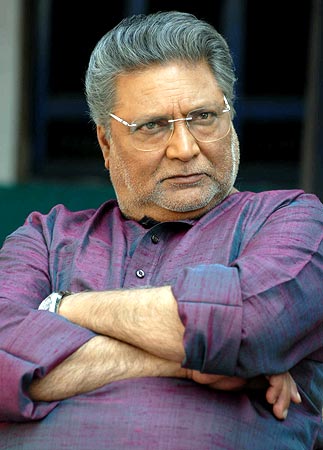

Isn’t there something utterly beautiful about Vikram Gokhale? That glow about him that hasn’t faded with time? And how little we know about him. Not much has been written about Gokhale in the national press and it is not surprising considering how cinema coverage in our national newspapers is synonymous with Hindi films and their poster boys and girls, their 100 crore clubs, their petty and sometimes serious controversies. Their brawls, their diet and exercise regimens. Regional cinema is not as well represented as it should be and even actors who have invested decades of committed work in regional cinema do not get much play time on prime time. It is only when one of them wins a pan Indian honour or is feted internationally that we sit up and take notice.

**

For Hindi film buffs, their earliest memory of Vikram Gokhale is in the 1977 film

Yehi Hai Zindagi. Directed by

K. S. Sethumadhavan, the film about an ordinary man’s relationship with God (decades before Umesh Shukla’s

Oh My God explored the same theme) pitted the natural brilliance of Sanjeev Kumar against the charisma of a young Gokhale who played Lord Krishna like a best friend in need. Someone approachable, easy to talk to, affable but at the same time uncomfortably frank. Aware of follies, of human vanity and full of astute observations. Even under layers of purple make-up and fake jewellery, he glowed like a divine being. You felt a thrill and a goosebump of two when he suddenly materialised out of nothingness, flute in hand, a knowing smile on his face and eyes aglow with insight. Among the many cameos he played in Hindi films, we remember him as the imposing Collector Jaideep Das Gupta in Amol Palekar’s delightful

Thoda Sa Roomani Ho Jayein (1990) who resents the match-making between him and a single girl he looks down upon. We remember him also as the police commissioner in Mukul Anand’s

Agneepath (1990) and as the autocratic patriarch in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s

Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam (1999) and more but this does not even begin to sum up the work he has done in Marathi cinema and theatre. And yes, even other languages.

**

Not to forget his work in television beginning most notably with Kavita Chowdhury’s 1990-1991 cult series Udaan where he played a rebel aristocrat who leaves the gender politics and stifling confines of an ancestral haveli to till his own land for years before its forcibly taken away from him. What begins then is a 20 year long battle against corruption, violent thugs and an ineffective law and order system. And ofcourse his bond with his family, especially his daughter who he moulds and shapes to be not a victim of circumstances but to become a high-ranking police officer. He spanned the distance between youth and the mellower years with the felicity of an actor who knows his craft inside and out.

**

Gokhale played a farmer, a weaver, a father, a husband, an idealist and most importantly a mentor to his children with conviction in

Udaan and it remains till date as one of the most brilliant and undersung performances on Indian television. He has however many other dimensions. He is an accomplished photographer, a social activist, a film director and someone who wears his lineage lightly even though he comes from a family of legends. His great grandmother

Durgabai Kamat was a path breaker as she busted gender walls and is said to be the first female artiste of the Indian screen. His grandmother

Kamlabai Gokhale had worked as a child in Mohini

Bhasmasur, a film produced and directed by none other than

Dadasaheb Phalke. His father Chandrakant Gokhale was an iconic Marathi film and stage artist. He has however built his own lineage, working on each performance with diligence and building a formidable body of work in the process.

**

Being named best actor (he shares the award with Irrfan Khan who won it for Paan Singh Tomar) at the 60th National Awards for his Marathi film Anumati, may have finally cemented his presence on the national consciousness. But regardless of any awards, the presence or absence of media attention, he will continue to work as he always has, with tenacity and passion. The fact that we know so little about his oeuvre is finally our loss, not his.

One of the best actors Marathi films and the stage has seen and loved. Uncomfortably frank without a care of what others will think – that’s him.