“I am the ‘memory keeper’. I have become a memory keeper because I was born wedged between the sunset of one era and dawn of another. Existing between eras is to live in a space where people forget to keep records because they are eager to forget the past and move on to the future. I keep memories for posterity,” says Sri Lankan artist Anoli Perera about her debut solo exhibition in Delhi titled Memory Keeper. The exhibition, as the title suggests, takes viewers to and beyond private and public memory mediated by the passage of time as well as war, and traverses through a number of other discourses that includes migration, globalization and advent of homogenous cultural forms and the expelling of the local. In her first interview in Delhi, Perera, one of the most renowned contemporary female artists from Sri Lanka, shares the memories that have and will continue to influence her art.

What do you mean when you say you are a Memory Keeper?

For most people, the last vestiges of the previous era and the transition itself, become insignificant moments and footnotes of history, not worth remembering in the larger contexts of events. But they are important in the nostalgias of people like me who don’t belong to the histories of either era because we happened to be born in between times. So now I am grasping for and committing to memory those moments and incidents that for many people would be insignificant details.

And what are these memories?

My parents grew up in an era that had missionary schools, convents, and a Governor General who hoisted the British imperial flag and sang very loudly God Save The Queen. I remember our annual holidays spent in my grandfather’s house, under the constant gaze of King George and Queen Mary in their regal grandeur looking down from a great big portrait hung in the dining room. It only came down after the house was sold off in the early 1980s, nearly 40 years after our Independence from Britain in 1948. From being Ceylonese, we became ‘Sri Lankans’ in 1972. We also closed our economy to many, nationalizing this and that. Rationing of bread, rice and many other things also started. That’s what people would say about the decade of the 70s. The frugalities of the time were soon forgotten amidst the Pizza Huts, McDonalds and satellite television. It was an era of veritable globalization and McDonaldization. By the end of 1979, we had lost the indigenous Burghers who by that time had migrated en-masse to Australia, and by 1983 we lost the Tamils…literally and metaphorically. With that came 30 years of fighting…fighting for land, fighting for pride, fighting for what was lost…what we lost was our innocence and our common sense. Then it stopped …Soon the pain and what was lost might well be forgotten too. But these memories will live with me for posterity.

And that is why your installation of a canopied bed enmeshed by lace panels is called Left Behinder?

Yes. For me, using a bed was woman thing, it’s an intimate space for any woman, and the laces are a symbol for our colonial legacy. On the bed, a trunk with a video installation is placed surrounded by a webbed-in constellation of bottles with food recipes encapsulated as posthumous references to the lost community of Burghers (Sri Lankan Eurasians). The title, Left Behinder, is taken from a poem by Jean Arasanayagam, a Dutch burgher Sri Lankan writer. The whole work tries to remember the diminishing presence of the burghers, most of who left Sri Lanka due to the uncomfortable political environment of the post independence era.

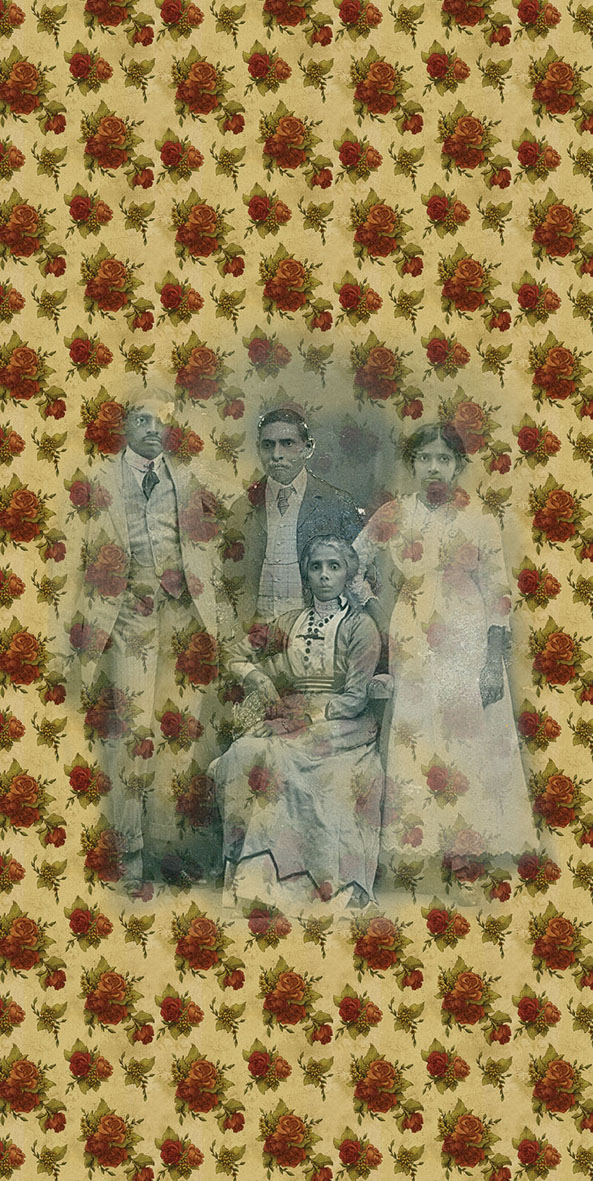

You are also planning to cover the gallery walls with large layout of wallpaper that have semi-faded figures as the central characters. Who are these people?

They are the ancestors of my piano teacher who is of a mixed ethnicity. I have used these photographs, and have blurred them, referring to a bygone era already lapsing from the collective memory of the present.

Three of your sculptural works – made like female but headless bodies – are called Ghosts of Swarna Bhumi. What is this about?

These three black, headless, tall, ghostly female figures are motionless with no heads and no feet. The swollen belly is installed with a video that can be seen through a magnifying glass and carries images of Sri Lanka’s recently concluded and immensely destructive civil war; Three more womb like forms are positioned on the floor connected by three umbilical cords to the standing figures. They too carry images of a violent past. For instance, in one of the images, a child is seen lamenting his father’s death in the war.

What are you expectations from this show in Delhi?

The sense of drama and spectacle in my work is something I feel will attract Delhi audience as it is far more evolved intellectually.

How has Delhi inspired you, if at all?

Delhi has so much to offer an artist. I have bought all my fabrics – so intrinsic to my work – from local markets here. Also I will certainly look at themes like garbage management and environment in my future work, issues which I face on a day to day basis here. Despite what sounds like problems, I feel at home here. India has so much cultural diversity, I will want to come back here again and again. These are memories I will never get tired of.

Memory Keeper open at Shrine Empire, 7, Friends Colony (West), New Delhi from January 18, 2013 till February 16, 2013

Poonam Goel is a freelance journalist and has covered the arts for over 15 years. She contributes on visual arts for various newspapers, magazines and online media. More about her on Story Wallahs. Write to her @ poonamgoel2410@gmail.com