Memories are like films. Some fade away and some are revisited again and again. Like my interview with Shama Zaidi. Years later, I can still remember her voice pulsing across a long-distance telephone line. As full of character as her writing. Zaidi’s body of work speaks for itself and she is one of the few authentic writing talents and creative visionaries Indian film industry has ever seen.

Her scripts smell of tactile sensuality, of searing loss, heart-break that you cannot bear, a culture of refined self-expression, of havelis and mansions and lanes and neighbourhoods stripped of their future. Her work is difficult to sum up in stock phrases. It all began with MS Sathyu’s cult classic Garam Hawa which to this date remains the most devastating critique of Partition. Yet, said Zaidi about the near-perfect screenplay she penned, “I sort of moved into writing unintentionally.’’

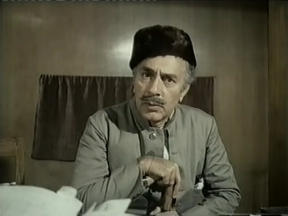

When we spoke a few years ago, she still had vivid memories of Garam Hawa and the furor it created. “It was all so pointless,’’ recalled she, talking of the bans and the mindless protests against the film’s pathos-filled description of Indian muslims in post Partition India. Poetic justice then, today the film is considered as an unequalled milestone not just for Balraj Sahni’s heart-breaking performance but for Zaidi’s unsentimental and yet profoundly moving screenplay. Then began her association with Shyam Benegal. Not only did Zaidi did the art direction of Benegal’s Nishant and Bhumika, she wrote the dialogues of the moving Mammo, again about a displaced, partitioned soul and Sardari Begum which delineated thumri singers, Trikal which was about a tumultuous phase in Goan history and Susman which depicted the struggles of traditional weavers. From Hari Bhari to Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, she has been involved with almost all of Benegal’s projects in one capacity or another. She also did the rollicking screenplay of Benegal’s hugely successful Mandi where prostitutes were for the first time portrayed as beings with humanity.

The last scene is my absolute favourite.

Jo door se toofaan ka karte hain nazara,

Unke liye toofaan wahaan bhi hai yahaan bhi;

Dhare mein jo mil jaoge, ban jaoge dhaara,

Yeh waqt ka yelaan wahaan bhi hai yahaan bhi…

yes wonderful work in superlative movies.

Btw, was the garam hawa screenplay not co-written by kaifi azmi, who also wrote the dialogue? and based on a story by ismat chugtai?

yes :))