Fame can be a compelling thing. To Die For, a 1995 Gus Van Sant film, inspired by one Pamela Smart (accused of instigating her husband’s murder), was really a comment on America’s bottomless appetite for televised fame or notoriety. To be remembered for something, anything is one of the prime human impulses today. Ever wondered why the Guwahati molesters did not hide their faces even though they knew they were being filmed? Or why the assaulters who beat women in a Mangalore pub in 2008 and recently in Padil at a resort had TV cameras in attendance? They wanted to be remembered.

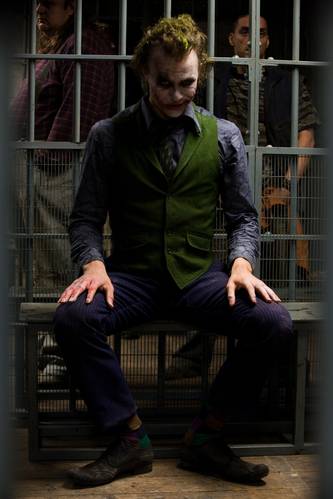

And why did terrorists choose to spectacularly demolish the twin towers in New York or turn the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai into a furnace? They too wanted the world to notice and acknowledge their power to destroy. And the random shootings like the recent one at Colorado during the screening of The Dark Knight Rises? There is no logical answer. Except that for a twisted mind, heart-stopping evil is an aspirational thing. Though we will never know exactly why the demented gunman chose The Dark Knight’s sequel to spray bullets on a room full of innocent people,is it possible that he was subconsciously revisiting the Joker or trying to replay him? Do films invest evil and violence with a certain glamour? Our heroes do walk in slow motion towards the camera after blowing up buildings And Heath Ledger’s Joker, was the most memorable face in The Dark Knight. There is ofcourse, documented evidence that scenes of violence subtly alter our world view. In some cases, they also alter our behaviour.

In 1995, Sarah Edmondson (19) and her boyfriend Benjamin James Darras (18), watched Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and shot two people. Darras shot and killed cotton-mill manager William Savage at point blank range. And Edmondson shot Patsy Byers, a store cashier who survived the attack but was incapacitated for life.The unlucky Savage was a friend of author John Grisham who publicly accused Stone of “being irresponsible in making the film, claiming that filmmakers should be held accountable for their work when it incites viewers to commit violent acts.”

In another copy cat crime inspired by a scene in Money Train (1995), a tollbooth was ignited, killing the attendant instantly. Though one cannot blame cinema for all the wrong in the world, it does blur the line between reality and make-believe, often confusing impressionable minds to believe that violence can be fun because if evil was so bad, why would it be packaged so compellingly? The Oscar sweeping success of films like The Silence Of The Lambs (1991) reinforces the lure of darkness. How many of us felt that we were watching a Hollywood disaster film when New York’s twin towers crashed and filled the streets with rolling waves of smoke and rubble? Who is to say what images fuelled the imagination that conceived these seemingly impossible attacks?

The debate also rages about whether films reinforce gender equations and life choices. What do item numbers tell the young about women? Do films glamourise smoking and drinking? Do films like Shaitan (random murders committed by unhinged young people) and Dev D (long scenes of drug abuse, a hit-and-run accident and no visible pangs of conscience) achieve anything positive?

Or maybe we are reading too much into projected images because there is a lot more to who we are as a culture and what we are becoming. When we watch a mob molest a girl and do nothing, we cannot blame cinema for our cowardice. We cannot blame corruption, honour killings, female foeticide, dowry deaths and acid attacks on our movies. At some time, we have to realise that evil is not just an action. Evil is also the refusal to take responsibility for our actions. Evil is also silence.

Yes, cinema is accountable for the messages it sends out to the young. But then so are we all.

Brilliantly written article Reema. To live as ‘responsible’ individuals should be the next step to ‘civilization’ since we evidently haven’t gotten there yet.