There is an unavenged little boy in Karan Johar. A son who saw his naively golden-hearted father not getting his due in an industry driven by merciless opportunism so it is apt that Johar should pick a Father India metaphor to replay and remake in the memory of Yash Johar. Karan Malhotra’s Agneepath tries to avenge the failure of Mukul Anand’s unpredictable and yet grand film that established three things. You should never mess with Mr Bachchan’s voice. No one can wear kohl lined eyes and a dapper suit like him. And no one can recite poetry as well and unleash as many goose-bumps as him. Though, one is absolutely sure that Harivansh Rai Bachchan would never have imagined his poem about resilience and courage on the path of brimstone and fire, being used in a cinematic context as a weapon of revenge.

Mukul Anand was famous for spectacularly mounted films that often fell short of a story well told. His Agneepath is remembered for the wrenching murder that sets the tone for the proceedings that follow. There was the absolutely and beautifully restrained Madhavi who Mr Bachchan once described as the only actor he had worked with who could drop a tear at exactly the same moment, every single time, no matter how many retakes were asked for.

There was the Nargis-Nirupa Rai and Kasturba mother figure (The unforgiving Rohini Hattangadi) who does not melt till her prodigal son gasps his last in her arms. And yes, there was that scene where Bachchan leans back in his chair, puts one never ending leg upon the other and rasps, “Naam Vijay Dinanath Chauhan..poora naam. Baap ka naam, Dinanath Chauhan..Ma ka naam Suhasini Chauhan..Gaon Mandwa.” And the quirks. His admiration for his nemesis Kancha’s (Danny dripping elegant menace) sophistication and his own awkward attempts to speak in English. Remember the “maut ke saath appentment?”

Ironically and intelligently, first-time director Karan Malhotra moves away from the blue oceans and yachts of Danny’s Kancha to create a world that is almost like a colour-coded graphic novel or an epic with grand metaphors set partly in the grainy, dark, restless island of Mandwa and then in the underbelly of Mumbai where chawls, meat markets, flesh markets, random murders and shoot outs jostle for mindspace. Where human-beings of the third gender and sex workers spectacularly protect those marked by violence in the world beyond their chawls. And even in the middle of a pointless item number, the hero finds himself in a ring of fire, invoking the chakravyuha imagery from an epic we all remember.

It is world where red vermilion explodes spectacularly on the screen, to highlight both anger and celebration. Where a Ganpathi idol is not a thing of distant benevolence in a pandal but an overpowering, physical presence that the camera caresses, where lamps dance, flags flutter and the hero sprints to remake cinematic history towards a dahi handi, climbs a pyramid of limbs and arms and then as he breaks it, we see a pair of grey, green eyes peering at us from a red stained face and we know already that this movie is going to work. Within its own context.

It is for someone else to decipher whether it has religious symbolism but within the framework of a sweeping revenge drama, it knows its own mind, the places it has to revisit, avoid, reinterpret, improve upon. And leave well alone.

The opening sequence in Mandwa is operatic in its tragedy. Whether it was Kiran Deohans or Ravi K Chandran who filmed it or some of the other key scenes, the cinematography is superlative as it lends depth, heart and palpable emotion to the story. Right from the beginning we know, the camera is the third dimension of this narrative as we see a young Vijay and his father on a projectile rock, framed against the sea and the invisible storm gathering around them. The murder itself is a long, shuddering, heart-breaking moment of many moments. We see the struggling feet of a man who has been hung.. encircled in the arms of his young son. We see from the gaze of a young child, indelible flashes of the murderer, his diabolical smile in the uneven light of the fire torches and the storm that won’t let up.

The director knowing very well he cannot top the corpse in the push cart sequence of the original, accords a quiet burial to Master Dinanath Chauhan. 15 or more years later, when the son returns as a young man intent on revenge, Mandwa is the land of darkness, the Lanka where the people who chose the devil over innocence are paying for their sins.

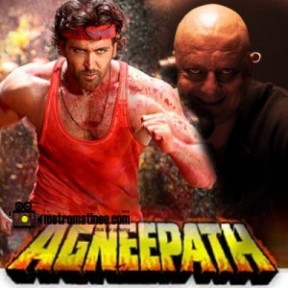

The banyan tree, the scene of an unspeakable crime, has dried up too. The only bleached sign of life is the ocean, still lapping restlessly. This film does not operate within the context of wrong and right, reason and logic hence murder, be it in Mandwa or in Mumbai happens without attracting any legal retribution. The policeman (Om Puri) for most parts is a bystander and onlooker. The power struggle between Rauf Lala (Rishi Kapoor), Vijay (Hrithik Roshan) and Kancha Cheena (Sanjay Dutt) unspools for most part, unchecked and uninterrupted.

Performances? Dutt’s willingness to look as ugly as his part in the story has created a character that is less a person and more a symbol of brooding, dark evil. His eyes do not shine and his abode and his physicality are packaged darkness that reminds you of a certain sorcerer after the soul of a young boy. He guffaws one too many times and is more convincing when just a grimace is doing all the talking but you can tell, he has relished this role after his recent outings in disasters like Rascals. His final confrontation with the avenger back from the dead, steers clear of the fabled Agneepath climax with its literal path of fire that Bachchan negotiated to reach his foe. Here the fire is internal and so in a graphic moment, the past comes full circle with Master Dinanath Chauhan’s ghost finally laid to rest as Roshan’s Vijay heaves out the lines,

“Yeh mahaan drishya hai, chal raha manushya hai..ashroo, swed, rakt se lathpath..lathpath..lathpath..agneepath..agneepath..agneepath.”

Roshan is an actor who never lets down a role. Ever. Here too, he carries the pain of a life time in his eyes. Compared to the 36-year-old man of the original, he is a young man in a hurry to end a story that began when he was torn from his childhood and thrown in a world of unsparing cruelty. He is spectacular at any given time but even more so when his vulnerability reaches out for empathy.

His methods are questionable though and unlike the original Vijay, he has no qualms about dealing with drug dealers or betraying those who have sheltered him because he just wants closure. At any cost. The young actor who plays him is fantastic too (as was the little Master Manjunath in the original) though his first crime is disturbing. On a different note, so are the scenes involving young girls being sold off to leering old men. We know it happens in real life but should young actors be subjected to such violence, even if make-believe on the screen?

And that brings us to Rishi Kapoor. Ladies and gentlemen, here is an ACTOR. So whether he is irritatedly asking for the pair of mojris someone else has walked away in or looking for lambs to slaughter and little girls to sell, you know he is in the moment, in the very heart of a dark, corrupted soul and even in the qawaali sequence, he reminds you that no one can quite carry a song like he does.

Priyanka Chopra. We will not be unkind but she reminds one of what a director once said about Nicole Kidman, “She is a good actor but how can you take her seriously after she botoxed her forehead?” Priyanka has not botoxed her forehead but it is the same principle. No matter how earnestly, she is singing or dancing or crying, all you end up seeing is her nose. Her lips.

Karan Malhotra has reworked the intensity of Ganga Jamuna, Mother India, Deewar and other such films to create cinema of visual and emotional triggers that is slowly making a come back with films like Dabangg. But it has a vocabulary that is its own, a sense of purpose that it sticks to despite occasional indulgences. The violence is hard to watch in places and the crying occasionally meanders into the Kuch Kuch Hota Hai zone but this is a film that is made for an audience looking for a cathartic and celebratory time at the movies. And it succeeds in giving them just that.

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight (http://www.flipkart.com/b/books/perfect-eight-reema-moudgil-book-9380032870?affid=unboxedwri )

wow..Reema..a very nicely written review 🙂 I always await ur reviews..they r a treat for any reader

so i should go and watch..right?!

Yes manoj, if you like a certain brand of cinema that is emotive, larger-than-life and sweeping 🙂