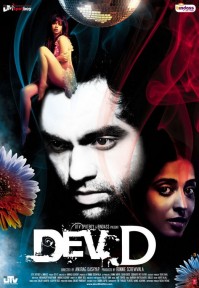

It began with Emosanal Attyachar. When I watched Dev D a few years ago, I felt as if my insides had been churned and that Sarat Chandra Chatterjee had died once again. There was nothing wrong cinematically with the film. The first half was visceral and brutally honest about the messy, inner universe of love. The lust, the anger, the impulsive severings that leave bloody nerve ends aching with pain. A pain that can ruin a life or many, if allowed to run its course.

It began with Emosanal Attyachar. When I watched Dev D a few years ago, I felt as if my insides had been churned and that Sarat Chandra Chatterjee had died once again. There was nothing wrong cinematically with the film. The first half was visceral and brutally honest about the messy, inner universe of love. The lust, the anger, the impulsive severings that leave bloody nerve ends aching with pain. A pain that can ruin a life or many, if allowed to run its course.

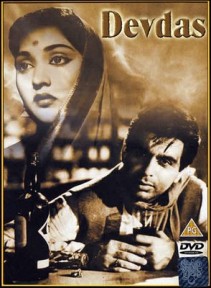

It was the second half that boggled me. Sarat Babu’s Devdas was as complex and as torn between life-and-death as Hamlet. It was not just the loss of love but the loss of self-esteem that made him drink himself to a slow, futile death. He killed himself because he could not live with himself or forgive his own cowardice for turning down the love of his life. The fact that he never had a second chance to redeem himself killed him.

In Dev D, I only saw a self-indulgent man without an emotional graph, curiously unmoved even by the fact that he had killed half-a-dozen people under his car in a drunken haze. I felt no sympathy for him. I felt nothing except revulsion. What really disturbed me however was just how much the film had connected with the young. The fact that the heroine was being called a whore, the fact that the sex worker in the film seemed to have found a sense of self in her vocation, evoked no questions.

In Dev D, I only saw a self-indulgent man without an emotional graph, curiously unmoved even by the fact that he had killed half-a-dozen people under his car in a drunken haze. I felt no sympathy for him. I felt nothing except revulsion. What really disturbed me however was just how much the film had connected with the young. The fact that the heroine was being called a whore, the fact that the sex worker in the film seemed to have found a sense of self in her vocation, evoked no questions.

But it was just a film, right? Why should it have mattered, one way or another? Maybe, I was going through the same wrenching sense of loss that my parents must have felt when the cinematic universe of Sahir Ludhianvi’s Barsaat Ki Raat degenerated into Meri Pant Bhi Sexy.

But it was just a film, right? Why should it have mattered, one way or another? Maybe, I was going through the same wrenching sense of loss that my parents must have felt when the cinematic universe of Sahir Ludhianvi’s Barsaat Ki Raat degenerated into Meri Pant Bhi Sexy.

This was not the first time the Hindi film audience had lost its innocence. There was Choli ke Peeche, the double entendre song sequences in the Jeetendra Sridevi starrers of the 80s and even some of our most celebrated item numbers in the recent and not so recent past that have thrown around words like jawani, mutton and Zandu Balm. We have come to accept that we do not have a Kaifi anymore to entreat his beloved to “Aur kucch der thaher.” Or Sahir serenading his woman with, “Choo lene do nazuk honthon ko.” Passionate love stories are passe. As is poetry. As is innocence. Or what was known as ‘nafasat,’ a refinement of thought, feeling and conduct. The world has changed. No one has the time for pretences or the need to string together a series of compliments for that ladki who was radiant like a temple lamp, soft like winter sunshine, perfect like a poet’s dream.

Love is not a thing of mystery and magic anymore in our cinema. It is an MMS scandal, a string of episodes strung together around Sex Aur Dokha. Love is today a reality show showing us that given a chance, no man or woman will stay committed.

Well, this is how things are and one must either learn to ignore cuss words in songs and the barren heartscape of our cinema or immerse oneself in the nostalgia of days when a heroine was a husne jaana, a Kashmir ki kali, ek ladki bheegi bhaagi si, a humdum, a dost.

Yet, there are times it is hard to either forget or forgive just how much our music and lyrics have degenerated. I recently caught a glimpse of Delhi Belly’s trailor on my TV and my son, who dismisses most hindi film songs as cheesy was intrigued by the song Bhag Dk Bose. By its rock vibe, its delicious guitar riffs. We spent many moments laughing over the song and I even posted it on my Facebook profile as a family favourite. Till ofcourse I discovered that the song was a refrain about a cuss word I have never known or been educated about.

I grew up beating eve teasers in a Punjabi mohalla and have a colourful vocabulary but this song is way out of even my realm of expletives. That a song like this is being touted as a youth anthem has again come as a shock though Emosanal Attyachar should have prepared me for this moment. What has really disturbed me however is that a song like this is appropriating mind and public space openly and even young kids like my son who have no idea just what its catch line stands for and are innocently singing it will sooner or later find out what it means. Is this the purpose of cinema? The argument that it is an adult film does not cut it. The song is out there playing between films and shows I watch on TV with my son. I resent the loss of innocence that filmmakers impose upon a generation that still has not discovered cynicism and still, if left alone, would like to come upon magic and romance in their relationships and in their lives.

I grew up beating eve teasers in a Punjabi mohalla and have a colourful vocabulary but this song is way out of even my realm of expletives. That a song like this is being touted as a youth anthem has again come as a shock though Emosanal Attyachar should have prepared me for this moment. What has really disturbed me however is that a song like this is appropriating mind and public space openly and even young kids like my son who have no idea just what its catch line stands for and are innocently singing it will sooner or later find out what it means. Is this the purpose of cinema? The argument that it is an adult film does not cut it. The song is out there playing between films and shows I watch on TV with my son. I resent the loss of innocence that filmmakers impose upon a generation that still has not discovered cynicism and still, if left alone, would like to come upon magic and romance in their relationships and in their lives.

I feel violated that in my innocence, I listened to a song with my son, that has not been written with an innocent intent. But then, as the film’s tagline says, “shit, happens.”

And because it does and because garbage and offal are intrinsic to the vocabulary of our cinema and our music today, I will just have to filter the air that blows into my home and protect whatever is left of my son’s childhood.

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight. (http://www.flipkart.com/perfect-eight-reema-moudgil-book-9380032870) . More on Story Wallahs. Other books by Unboxed Writers in our Store

I don’t know the cuss word around which that song is ‘constructed’ either, and I too am dreading the loss of my eleven year-old’s innocence … when she hears words she can’t understand from friends who have older siblings, and comes and asks me about them (thank Gos she asks me, at least) … when she plays Rihanna’s latest hit number that laments the protagonists’ own depravity and infidelity and her inability to control her own actions … are these the messages our children are growing up with? That it’s all right to do unethical stuff, to hurt those who are closest to you, and then lament that you have no control over it? I am seriously disturbed and intimidated in my endeavour to raise my child as a responsible, thinking human being!

Excellent, excellent piece Reema! I cannot even tell you how much this piece resonates with me. I mean despite being brought up in the 90s, Bollywood classics were always appreciated and played at home, which gave me an alternative to 90s ‘Pant bhi sexy’ type crap.

It’s tragic that young Indians are losing their taste for ‘nafasat’, as you put it. I feel seriously disturbed with 90s style crass songs like Sheila Ki Jawani resurface and become hits. I thought we had matured since, but we clearly haven’t.

omg! yes Reema ! i’m generally not much intrested in movies n tv so i’ve never come across Bhag DK Bose song. When i read this article, i logged in yotube n listened.. Telecatinf it pubilically is certainly a kind of trespass.

As far as dev-d is concerned, the hero is a person who is addicted to drinking, whole world is against him. but he is not bothered. For him life has got no purpose. Yes he was self induldent man with no emotional graph, but that’s the way he is and he acceps it and what other people think of him never mattered him. He was not a hypocrate. He lacked a very basic thing of life ie someone to love and someone to be loved by. And eventually found that sex worker. It was an adult movie and i don’t think there was any thing wrong with the movie.

Songs like Mere Pant Bhi Sexy is a byproduct or kind of a reaction of our society’s creating too much of taboo around sex.

Yes, the loss of innocence is tragic. I believe that the loss of of innocence has become like an epidemic now, everyone is initiated into slang, abusive language, hardcore sex and the brutality of life. Call it realism if you will, as Reema has put it so beautifully, what of the magical realm of love which is forever closed to these youngsters? The nazaqat lost, the nafasat gone, media shoves reality down the throat and our children gulp it down knowing no better. It’s hard for parents of today to see their children become so rude, flippant and bitter even before they have savoured the sweetness of life.