The world is divided between them and us. Between the disempowered and the powerful. Between survivors. And oppressors. And what better way to tell a story about dispossession, migration, transition and struggle than to assume not just one voice but many? To narrate not just one but diverse histories embodied in Japanese mail order brides in a boat, being carried over a century ago, away from poverty, shadowy, occasionally traumatic pasts towards San Francisco. To the American dream packed with promises of first class hotels, cherry orchards, homes with picket fences and a thousand acres of a golden field. And “someplace fancy with white tables and chandeliers.” With pictures of unseen, as yet unloved husbands in tiny oval lockets, thick brown envelopes, in the sleeves of kimonos, silk purses, old tea tins and red lacquer boxes. And then the reality of unromantic consummation with husbands who had not yet reached the American dream but wore black knit caps and shabby black coats and took their wives to settle to the edge of towns, to bunkhouses, barns, packing sheds, orchards, labour camps, ranches and fields to do back-breaking work.

**

The women fear the faces they cannot yet read. Social mores that are not yet legible. Words they have not yet learnt. They fear that, “Whereever you go, you are always a stranger and if you got on the wrong bus by mistake you might never find your way home.” And the realisation that for better or worse, “Home was whereever our husbands were. Home was by the side of a man who had been shovelling up weeds for the boss for years.” Along with the thought that,”If our husbands had told us the truth in their letters-they were not silk traders, they were fruit pickers, they did not live in large, many-roomed homes, they lived in tents and in barns and out of doors, in the fields, beneath the sun and the stars-we never would have come to America.”

**

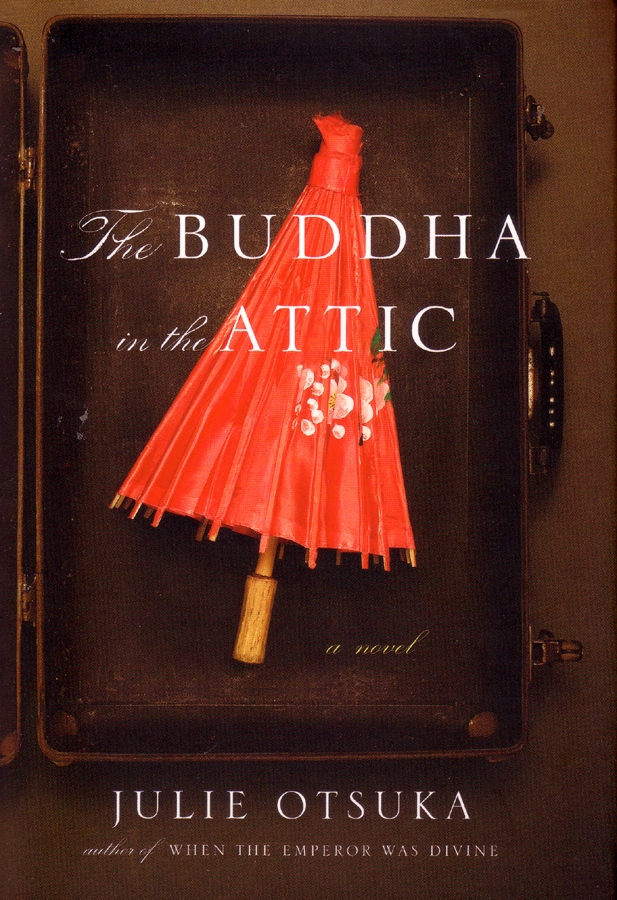

Julie Otsuka’s The Buddha in the Attic is like a long Haiku that though divided in eight chapters and over 130 pages long, is concise like a mathematical equation but with the roaring, ocean heart of an epic. Bursting with exquisite detail, ripe with a million vivid pictures, the book is still so minimalistic that nothing comes between the narrative and the reader, not even a single extra word, emotion, smile or tear. The spare, bare-boned, metallic prose cuts like knife but is deeply stirring, moving, empathetic and humane as it takes us into the hearts, wombs and pain and heartbreak and courage of women who came with nothing to America and then gave all they had to a country that gave them little and this is the story of hundreds of them as they become wives, field hands, cooks, dishwashers, maids, mothers, widows.

**

And some even learnt to not flinch while selling their bodies for a few dollars when times got desperate because, “In America, you got nothing for free.” And so the women persisted and “cut out pictures of cakes from magazines and hung them on the walls, sewed curtains out of bleached rice sacks, made Buddhist altars out of overturned tomato crates” and sometimes indulged themselves with a bottle of coke, a new lipstick, a new apron and survived through bad times, violent times though sometimes they, “forgot about Buddha. We forgot about God. We developed a coldness inside us that has still not thawed. We stopped writing home to our mothers. We lost weight and grew thin. We stopped bleeding. We stopped dreaming. We stopped wanting. We simply worked, that was all. And often our husbands did not even notice we’d disappeared.”

**

And then the broken marriages, the illicit affairs and the children. The women gave birth to them under oak trees, beside wood stoves, on windy islands, dusty vineyard camps, old silk quilts, in barns, on thick beds of straw, in apple orchards and entrusted them to hope and fear and an uncertain future. Some women died in childbirth. Some babies died too. Some survived. To grow up in ditches, furrows, wicker baskets and to sleep with their mothers like little warm puppies and to play like calves in the fields. But they too, like their mothers grew up with the longing for “fancy white houses with gold framed mirrors and crystal doorknobs and porcelain toilets.” And they too had heard that, “Whereever you go, you are always a stranger and if you got on the wrong bus by mistake you might never find your way home.”

**

And then they grew up to become a bit less estranged from this adoptive country because they spoke perfect English, they were educated here and they “insisted on eating bacon and eggs for breakfast” and whenever they caught their mothers clapping their hands in prayers, they “rolled their eyes and said, Mama, please!” And mostly were ashamed of their mothers, their poverty, their lacks, their history The straw hats. The calloused palms, They wanted to be doctors. Stars. Teachers. And even though the mothers, ” saw the darkness coming,” they said nothing and let their children dream on. And then the war. Pearl Harbour. The talk of mass removal of Japanese. Orders for them to be interned. The arrests. The mysterious deaths of husbands. Neighbours. And then the exodus once again and all traces of the women and their children and their stories and their journey so far… gone. Leaving behind shuttered homes. Forlorn pets. Ringing telephones. Wilting tulips. Weeds in the lawns.And a laughing Buddha in the attic. Almost as if they had never taken that boat from Japan and come in search for a future full of promise. As if they had never existed.

**

This is a book about not just one kind of dislocation but many. Spiritual, geographical, personal. And not just of one group of people but many who are driven by poverty to soils they can never flower or root themselves in. A book that speaks of a terribly tragic chapter in American history without ever becoming maudlin. A triumphant book that bows its head and grieves for women who left their homes but could never find another.

Your review makes me want to find a copy right now. Thanks for sharing. I’ll definitely have to read this one!