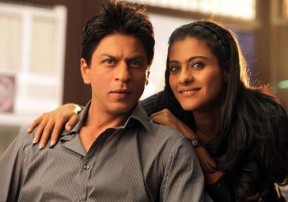

The turning point in the shared history of Raj and Simran in Aditya Chopra’s Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (DDLJ) comes when she finds herself in the same room as him after a night of drunken mindlessness and worries if she has done the unthinkable. He convinces her that she hasn’t and she collapses in a heap of grateful tears and falls in love with him. Similar scenes had appeared earlier in films like Aandhi and Zamane Ko Dikhana Hai but this one is the seminal point of conflict between the traditional India and the India waking up to the so called Western permissiveness in the mid 90s. DDLJ treated this scene as a definitive keynote in the relationship between a repressed Indian girl and a global Indian who could flirt outrageously, drive racing cars, play football with the goras, quaff beer and yet love his and her parents and outdance the jaats in bhangra on a Punjabi terrace.

The colliding world views inculcated by their families were the only conflict that the duo had to overcome before they could catch a train to the everafter in a simple world unmarked by racial tensions. A decade and a half later, Raj and Simran morphed into Rizvan and Mandira and the idyllic DDLJ gave away to the complex world of Karan Johar’s My Name Is Khan.

He has Asperger’s Syndrome and she has been married before. They are no longer two kids finding each other in resplendent mustard fields and flower spangled European meadows. They have real pain in their pasts and find love in a crowded salon over other people’s heads and the most romantic thing he does for her is to take her in her bedroom slippers on the top of a hillock to show her how the city that she loves, emerges like a dream from the morning mists.

They get married without too much fuss and are in a room alone again but this time there is no dichotomy between his morals and hers. But there is an elephant in the room. They are two Indians in America. And he is a muslim in a country that will be divided irrevocably post 9/11 into two halves called Us and Them. And between potential victims and suspected terrorists.

The two end up paying a huge price for their muslim surname in a world where the Indian diaspora is no longer sure of its place.

A world where the global Indian has become just an Indian who could be a muslim who could be a terrorist. Like Rizwan says, the time line of history in the West has been marked by BC and AD and now 9/11 and nothing will ever be the same again. A man chanting a muslim prayer will be hauled away from an airport to be combed for explosives and knives or put in jail because his name is Khan.

And even though the two are victimised beyond endurance by the turn of events in the film, punished for having a muslim surname in many different ways and never will have a painless everafter, they find ways to surive and to love each other even though the world they knew, no longer exists.

It is an unusual ground to explore for a mainstream filmmaker like Johar and despite its unwieldy second half, MNIK broke new ground in that it let a love story ask what would happen if violence, prejudice and hate were not answered with more of the same? What if the cycle of violence was broken by a simple desire to repair rather than destroy? What if unlike the muslim protagonists of many films post the Mumbai riots in 1992, this muslim refused to play either a victim or a violent terrorist?

In a lesser film like Kurbaan, a Karan Johar production again, love is once more caught between revenge and redemption when a man from Afghanistan whose family has been destroyed by American bombing of civilian areas, marries an America bound Indian girl and then plans large scale destruction of New York’s subway system. Just goes to show that even dream weavers like Johar cannot any more create love stories without taking into consideration the many changes Indian identities have undergone since the 90s. Love must take cognisance of changed gender equations, burgeoning ambitions, personal inhibitions and divisive ideologies.

Aditya Chopra’s DDLJ, still the definitive love story of the 90s has spawned many variations in the mercurial times we live in, most notably Jab We Met, where the strength seeking, dependent on everyone for her right to live her life, Simran is transformed into Geet, a girl who leaves her mustard fields and her large, happy family to chase her dreams and her love on her own terms, without fear and apology and even when she falls on her face, she resents being rescued by the man she had rescued earlier.

The point of conflict here is the heroine’s sense of volition which takes the entire duration of the film to zero upon who or what she wants. The just missed train here is a metaphor for missing out on the journey you want your life to be and a relationship is built not around European daisy fields but on the streets of Ratlam, in a seedy hotel where unlike the coy Simran, Geet threatens to use her martial art skills if the hero tries to force himself upon her. Geet is symptomatic of the times when women are unafraid to be in love and yet are vulnerable because their bravado is misconstrued by those who cannot return their love with the same generosity of spirit.

In the more recent Band Baaja Baraat, the gender roles reverse totally because the woman is the dream driver, the one who teaches the boy to become a man by giving him a livelihood and a perspective on life and love. Unlike Simran, Shruti initiates intimacy and remains unapologetic about it even when the man in question refuses to fall in love with her. A few tears and heartburn later, she moves on the idea of a marriage that promises security and falls back in love only when the errant lover grows up and acknowledges his feelings for her, fair and square. In films like Tanu Weds Manu, the woman is unapologetic about making mistakes and brave enough to rectify them.

The woman in love is no longer a wilting wall flower in Hindi cinema and a love story is not just about holding hands and singing songs but about fighting through issues, working for livelihoods, mourning losses, growing apart, growing up in a world where love is impacted by politics (MNIK), economics (Band Baaja Baraat), geography (Love Aaj Kal), shifting perceptions (Jab We Met), violence (Kaminey) and deviant sexuality (Saat Khoon Maaf).

It is an interesting shift in the narrative. One that tell us that when things mutate, fall apart and change around us, finding love can be a difficult thing but certainly not impossible. Comforting thought that.

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight (http://www.flipkart.com/b/books/perfect-eight-reema-moudgil-book-9380032870?affid=unboxedwri )

This story was carried in her column in http://tlfmagazine.com/

I’ve always believed in Simran’s dreams and with the changing times..always felt how oddly her dreams fail to fit in TODAY..but u open up another side of the story..yes..love stories have come a long way since DDLJ..the idealistic view has metamorphosed…thankfully…we are stronger now ! 🙂

It was delightful to follow this writer’s stream of thoughts, remember the films.