The poster for Memories in March read – “separated by memories… united by grief”. For little over 100 minutes of this Sanjoy Nag film, we see reflections of life refracted through the memories of Arati (Dipti Naval) who has lost Sid, her only son in a tragic accident, Sahana (Raima Sen) who was in one-sided love with Sid and a male colleague Ornob (played by Rituparno Ghosh who also happens to be the writer of this film) who Sid was in a love-relationship with.

The poster for Memories in March read – “separated by memories… united by grief”. For little over 100 minutes of this Sanjoy Nag film, we see reflections of life refracted through the memories of Arati (Dipti Naval) who has lost Sid, her only son in a tragic accident, Sahana (Raima Sen) who was in one-sided love with Sid and a male colleague Ornob (played by Rituparno Ghosh who also happens to be the writer of this film) who Sid was in a love-relationship with.

This film scores over many others in trying to keep things simple even though dealing with the subject of homo-sexuality. There are ample references to Ornob being too knowledgeable about Sid’s personal life early in the film, and of him frequenting the accident spot – yet, it comes as quite a revelation when Sahana, breaks to Arati, the exact nature of Sid’s bond with Ornob. As Arati copes with her son’s loss, this new found dimension to his sexual choice suspends her in a personal dilemma as well.

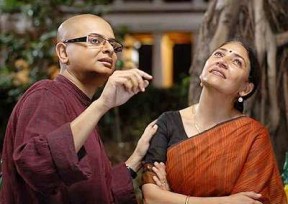

And she admits to Ornob that behind the facade of a sophisticated woman lies a ‘conservative’ person who is unable to cope with her son’s alternate sexual choice. In probably one of the most touching sequences, Ornob poses a question – “What is more unacceptable to you – that your son passed away or that he was gay?” As if to put forth his own bereaved angst he adds, “atleast you had two emotions to switch between. For me, it was one solid ball of grief”.

The maturity of the storyline holds sway when a few scenes later, the mother asks Ornob if he will remember Sid forever or he will find a new companion. Ornob confesses that such a possibility can’t be ruled out even if there isn’t an iota of such blooming at that very moment. Here again the mother faces a truth which is so intrinsic to the relationship possible only between a parent and the child. Through these thick and thin strands of grief, Ornob and Arati came close to each other.

When did we last see a Bengali film ( though the film’s language uses Bengali, Hindi and more predominantly English as its spoken text) that deals with a claustrophobic subject yet not smelling a bit of nostalgia? So the markers of a typical ‘arty’ Bengali film are not quite apparent with an ensemble musical soundscape rendering only Hindi numbers depicting mostly the love of Radha and Krishna at the back-drop of Ornob and Sid’s poignant separation.

But the film does falter still in the extremely sluggish proceedings. The first half is way too artificial – a warming up of the plot that takes too long. In-spite of the touching conversations between Ornob and Arati which light up quite a few screen moments, the excessive verbosity lets the film down.

In addition, the alternate sexuality theme and how the characters and how society deals with it (the society’s participation is important since I viewed the film in one of the most exquisite cine-viewing theatres in Kolkata and distinctly heard mocking jibes and banter from the audience during some of the most tragic scenes) was so over-played from the beginning that the fact of Arati’s arrival in Kolkata when her only child dies, gets sidelined.

But Ornob’s conflict-stricken emotional graph is so poignantly carried out through out the film that in moments of his personal loneliness and repressed hopelessness, we as audience feel helpless too. Ornob surely stands out as an avant-garde homosexual character in Indian cinema.

Soumik Halder’s camera continues to carry his signature, so do Debojyoti Mishra’s soulful compositions. Dipti Naval as Arati Mishra is grace personified till the time her emotional integrity is scratched. She gives a powerful performance but lacks support from the script. However Rituparno Ghosh’s Ornob is indeed a surprise to me. His rendition makes Ornob come alive as a supremely sensitive being, almost philosophical in his minimalist vision of the world round him.

Given the intelligent brew of language of the film, it will surely reach out to a wider audience. The contemplative nuances will pave way for festival participation as well. Whether the film with its middle-aged central characters and the pace, will be received well by a memory-less generation, remains to be seen.

On a parting note, apart from the core characters, all the others – the caretaker of Sid’s apartment, the driver of Ornob and the flock of children at Sid’s building sported predominantly white or the lighter shades of the palette. Sanjoy Nag’s future ventures will probably reveal his take on the outer life – beyond memories not necessarily woven by grief.

Amitava Nag edits cinema magazine Silhouette and writes extensively on cinema. His first book of essays ‘Reading the Silhouette: Collection of writings on selected Indian films‘ (LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing, ISBN-10: 3838396189) was published in 2010. Amitava also writes poems and short fiction in English and Bengali. Amitava works in a software company but dreams of making his own film one day.