Watching Lasse Hallstrom’s Chocolat always revives me. And turns life into a piece of deeply dark, melt-on-the-soul chocolate. And its not just the luscious imagery of chocolate being pounded, melted, tempered, crafted and moulded into temptation that sates the senses. It just feels so right, this film because like a cup of chilli spiked hot chocolate, it awakens (like a dialogue in the film conveys) something dormant within. Those parts of the soul we have given up on. Or lost in battle. Or just forgotten. The film celebrates the desire for more no matter where you are stuck in life. In habit. Dogma. Fear. Prejudice.

There is this old widow Audel who has been mourning her dead husband for decades and has forgotten to notice the diffident affection of Guillaume Blerot, a lonely old man with an old dog who watches her being chaperoned by old ladies, wistfully. There is Josephine (Lena Olin) who has been battered into submission by her husband and can’t leave him because she thinks she can’t. There is Comte Paul de Reynaud (Alfred Molina) who snips in private, the abandoned dresses of his absent wife who has left him but in his public life, imposes rules of bitter abstinence on the village, forbidding even simple joys. There is Caroline (Carrie Anne Moss) who has stiff rules about right and wrong and won’t forgive her mother Armande (the brilliant Judi Dench) for being free spirited and for defying her age and her diseased body for a few moments of joy. Caroline won’t let her own son ride a bicycle or meet his grandmother or let him have a mind of his own or even a piece of chocolate. It becomes clear as time goes by that she resents her mother something she has never had. The capacity and courage to live life without fear or apology.

And then in this village of restricted minor and major freedoms and enforced tranquility, comes a whiff of wilful North Wind and along with it Vianne Rocher (Juliette Binoche), a restless traveller and inspired chocolatier along with her daughter to offend sensibilities with her colourful high heels, her fiery refusal to be religious, or to be church and guilt bound. she has a knack of sensing lacks in people who walk into her chocolaterie by chance, accident or pulled by curiosity. The Mayor senses in her an instant enemy because unlike others, she listens only to the wind blowing in her soul. And to chocolate and its secrets. She has no sense of shame in admitting before him that she is an unwed mother, that she is not religious and he knows, she will break open the shells of denial and self-mortification that he has trapped everyone in. She with her little trifles, her deep, dark, tempting treats is far more powerful than the sermons he directs a young, naive priest to read out every Sunday in the church.

In a village that has forgotten to live, Vianne’s chocolate teaches passion to jaded couples, defiance to a battered wife, hope to a couple whom youth and love have passed by. She orchestrates meetings between Armande and her grandson over cups of hot chocolate and slices of sinful cakes. The most liberating thing about Vianne is her disregard for anything but pure, human empathy. She does not fear the village’s boycott of her shop, the calumny against her character. She keeps going. Keeps reaching out.Even to the reviled “river rats,” the boat gypsies who are treated with disrespect and suspicion by the villagers. She does not fear even the enraged husband of Josephine who breaks into the chocolaterie one night to beat her and drag her away from the influence of Vianne. “She doesn’t even know how to use a skillet,” he roars. Josephine knocks him senseless with one and snaps for the first time in her life,” Who says I can’t use a skillet?” She is now a whole woman. And will repay Vianne with solidarity and loyalty at a crucial time in the film when Vianne has had enough of her own courage and wants to leave the village with her daughter for a safer, more hospitable place.

Based on the novel by Joanne Harris, the film reminds us of the things that stop us from living our lives to the full. Do we fear what others will think about us? Have we been conditioned to associate joy with guilt, courage with foolishness, self-worth with shame? Are we always in a state of doubt, fear, anger, malice, suppressed angst? Chocolate in the film is a metaphor for a life lived in the moment, with complete awareness of its fullness, its beauty. It also reminds us that religion, is not about divinity but humanity and like the young priest says in the end, “Let us not measure our goodness by what we deny ourselves but by what we embrace..not by whom we exclude but who we include.” The film advocates a sense of abundance in the face of denial. Of grace in the face of vicious malice. Of facing conflicts with a slice of chocolate cake and if need be a skillet. It celebrates the courage of being different in the face of rigid conformity.

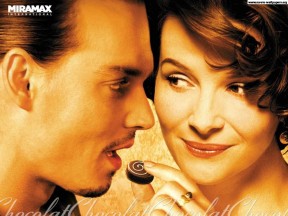

The film is about life questions. About answers that are all around us if we would only trust ourselves enough to hear them. And then there is Johnny Depp who like a guitar note wafts into the film and drifts through the frames with that loose-limbed casual grace that you know cannot be affected and touches every scene he is a part of with what can only be described as effortless magic. Binoche is strong with an understated, natural dignity and we read her resolve to live on her own terms in a slight jut of her chin, in her square gaze, her tick-tocking high heels, in her assured body language, her even, gentle voice. Judi Dench ofcourse habitually steals every single scene she is in. And there is Molina as the Mayor who owns that devastating scene in the end when he takes a knife to the chocolaterie to destroy temptation but ends up giving in to it and losing all sense of restraint in an orgy of enjoyment that shows him his own humanity and the futility of judging others for theirs.

This is a visually beautiful film. The scenes at the chocolaterie almost have a sensual charge as they celebrate the joy of cooking and feeding. The party sequence where Armande’s 70th birthday is celebrated and the lantern lit evening of music and celebration is exactly what totalitarians fear in every society. The human need for freedom and joy that will defy everything that stands in the way of fulfilment no matter how many rules and ‘supposed to’s’ are imposed upon individuals.

Chocolat is an uplifting, cleansing and healing film in a way that settles not scores but doubts and disputes. And asks that we be true to ourselves and be kind to others who are struggling to find themselves or a way out of pain and fear. Maybe, they need us just to listen to what they have to say. Or maybe, some music, a few friends around a candle lit table, a gift, a smile or just the silence of empathy. Or maybe, just a cup of chilli spiked cocoa to set everything right.

with The New Indian Express Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, Bangalore, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, an artist, a former RJ and a mother. She dreams of a cottage of her own that opens to a garden and where she can write more books, paint, listen to music and just be.

with The New Indian Express Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, Bangalore, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, an artist, a former RJ and a mother. She dreams of a cottage of her own that opens to a garden and where she can write more books, paint, listen to music and just be.

🙂 🙂 my favourite film! i so look forward to your write-ups on cinema among other subjects too. beautifully written yet again!