Night descends on M V Sarbajaya as the launch moors in the Sunderban waters calling it a day. Its inmates, a group of eager tourists, seek ways of merging with the mystic of the darkness surrounding them, a darkness that holds the promise of the royal Bengal tiger. We are part of that group which has travelled a long way from different cities to catch a glimpse of the formidable animal, a sight the local people would rather avoid.

Much is at stake when it comes to co-existing with the tiger, but for us, tourists who do not share the anxieties of the locals, the journey is culmination of an exotic dream.The dream had gained pace earlier in the day when an AC coach had ferried us from the West Bengal Tourism Development Corporation (WBTDC) office at Esplanade in Kolkata to a nondescript village in the suburbs, Sonakhali. Our arrival in the village rolled out the promise of some swift business for the petty shopkeeper, the cycle-rickshawallah, the tender coconut seller and hungry kids who gingerly inched towards us for loose change. An equally nondescript ferry waited to take us to the launch and soon we were a class apart. The package deal included sprawling bunker beds, both AC and non-AC, an upper deck with an enviable view and a crew to take care of us for two days and one night.

As the launch rattled its way through the waterway, our guide Mandal led us into the enigma that is ‘Sunderban’ or ‘beautiful forest’ in Bengali. Apparently, the name Sunderban is derived from the Sundari tree, predominant in the region. It is a land where hundreds of creeks and tributaries of Ganga, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers mingle, a land home to the largest single block of tidal, halophytic mangrove forests in the world. As we crisscross through the islands that adorn the Sunderban (of the 100-odd islands in the region, only 54 are inhabited by humans), we try to keep pace with Mandal as he identifies the sangams effortlessly.

Situated mostly in Bangladesh, the Indian side of Sunderban is estimated to be only 19%, covering an area of 4,264 sq. km. The mangroves are nothing we had imagined them to be. Here the tree roots garner as much attention as the trunks and leaves do. The two main roots found in Sunderban are stilt and breathing roots, Mandal tells us. While breathing roots are exposed to the air, stilt roots, according to botany textbooks are ‘adventitious roots that develop on a trunk or lower branch that begin as aerial roots but eventually grow into a substrate of some type’.

Given that the mud in these mangroves is oxygen poor and unstable, the roots display a great responsibility in holding their plants together. As they stand high on their toes or weave snakelike through the expanse of the tiny islands as though delicately balancing the vegetation, our eyes first fall on them before reaching the green leaves.

Our first stop is at Sudhanyakhali, uninhabited by humans but home to several animals. As we noisily make our way to the WBTDC watch tower on the island, we spot the rhesus monkey, monitor lizard, bronze-winged drongos, the several-hued kingfishers, bee-eaters, and spotted doves. The royal Bengal tiger keeps us waiting. Suddenly there is some activity by the pond; a monitor lizard leisurely rummaging through the fallen leaves looks up, a herd of spotted deer runs helter-skelter and even before we can grasp it, a huge black bird swirls in the air to quickly hide behind a tree. We strain our binoculars on the spot but do not see the black bird. Mandal is sure it is the Changeable Hawk Eagle, a rare audience. We head back to the launch as we have to reach Sajnekhali watch tower before it is dark. The forest department is very strict about its rules. Sajnekhali too has no human settlement, apart from the WBTDC lodge and Interpretation Centre.

Once again we sight the monitor lizard in its elegant stride, the black-headed and common kingfishers, monkeys, deer; the only additions are a huge crocodile that lolls on a pond side like a statue and tortoises jetting their heads out of the pond. We learn, much later during our travel, that those tortoises we saw were terrapins or Batagur baska, a very rare species native to West Bengal and Orissa, now on the brink of extinction. Once caught by fisherfolk for its meat, the terrapin that grows up to 60 cms is now being specially bred at Sajnekhali to save it from extinction. After four futile years, for the first time in 2012, the forest department was successful in breeding it in captivity. As per the department’s report, 25 hatchlings were born that year. As we gather all this information about the terrapins, we regret not having paid greater attention to the snouts that surfaced from the pond time to time.

Meanwhile, the tiger, which we are so consumed by, still eludes us. It is 5 in the evening but the night has set in. Soon darkness engulfs our launch and noises of the night take over; the noises are all from the human world. Chatter on the launch and drumbeats from a nearby island! The tiger does not roar. The drumbeats go on late into the night and we wonder whether they are to keep the tiger away. The lure of prey from human settlements is so high that the tiger prowls close to the villages in the night, we are told. Several speculations are afloat

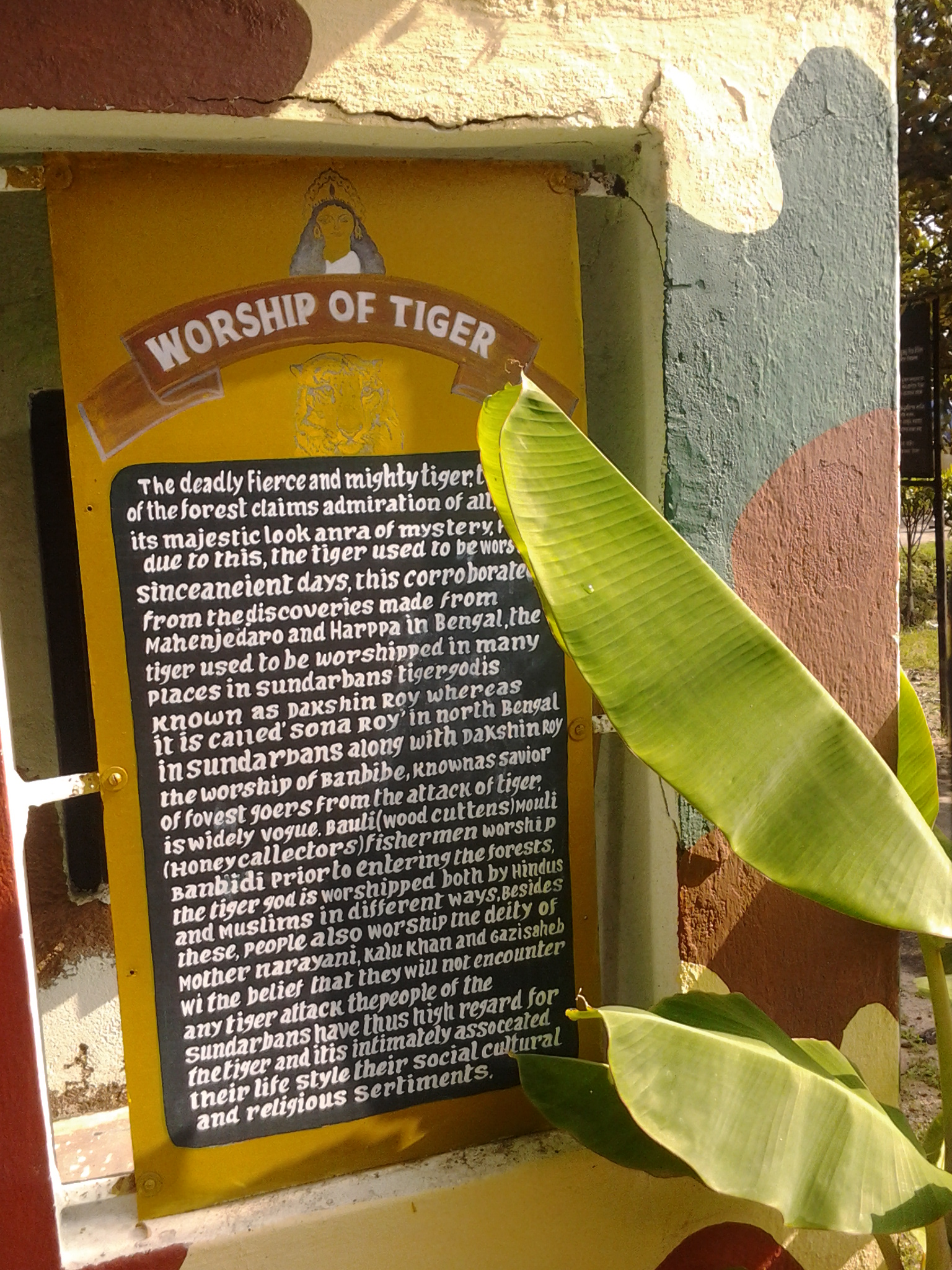

as to why tigers in the region love the human flesh. Some say it is the hardships of hunting in hostile terrain; others believe tigers have got accustomed to human flesh by eating bodies swept away in cyclones or preying on honey collectors who go into the forests. There is also one theory which says the salt water they consume has inherently changed their taste! Whatever the reason, the tiger is a force to reckon with everyday. The one and only who can protect them from the tiger is Bonbibi, a forest goddess venerated by all castes in the islands. Legends galore about this ‘daughter of a Muslim faqir’ who along with her brother Shah Jangli is believed to protect the people from the tiger. Honey collectors and wood cutters offer her special prayers before entering the forest. As we pass many uninhabited islands, Mandal points to the red-coloured cloth tied around some trees. They are for Bonbibi. Soon it becomes a game for us to identify the red markers.

Sandhyakhali and Sajnekhali, like many other Sunderban islands, have ‘shrines’ dedicated to the goddess. Only in islands like Godkhali and Durgapur colonized by people does Goddess Durga take over. Next morning as we tumble out of our beds, the launch had already set sail to Dobanki, our last destination on the WBDTC package tour. With the sun justout and the launch nowhere close to the human habitat, we hope for many more wild encounters. We train our binoculars on kingfishers, plovers, sandpipers,whimbrels, redshanks, little and great egrets, spotted deer, and a crocodile basking in the morning sun who quickly disappears on hearing us. At Dobanki camp, as we make our way through the half kilometer canopy walk located 20 feet above the ground, the mud flats below hold mollusks, scores of fiddler crabs in bright orange and yellow colours and mud skippers. The tiger continues to elude us. But there is Mandal igniting our hope by constantly seeking tiger clues.

After a half-day long cruise through the Sunderban waters, our launch drifts along the rising tide towards Sonakhali, signaling the end of the package tour. But we are nowhere close to saying goodbye to Sunderbans. We decide to return to Sajnekhali, where we had a dormitory awaiting us for two more days, and this time we choose a long but cheaper route to get to the destination. With Mandal by our side, we hop into a rickshaw that takes us from Sonakhali to Godkhali, from there a ferry to Gosaba and a cycle-rickshaw to Pakhirala. Pakhirala, once an abode for migratory birds (hence the name), is fast-changing to be a tourist-abode with many private hotels raising their heads to sell the Sunderban dream. The road to Pakhirala is a narrow strip amid fields, dotted by small houses with ponds and little room for motor vehicles. Our rickshaw puller is curious to know where we are from.

He is familiar with Bangalore, Mumbai and Kerala as many from his village have migrated to these places in search of better pastures. His son works in a garment factory in Bangalore and is happy making more money than he would back home, the old man tells us. He is happy too; rickshaw-pulling is both laborious and unyielding. Now, with tourism picking up, there is fast buck to be made by selling land to private operators from Kolkata to build hotels. But opportunities cease there and migration is their only option.

Though surrounded by water, fishing is no longer a sought-out occupation in Sunderban. With some education to boot, the younger generation aspires for jobs that will elevate them from the tides that ebb and flow dramatically through the day and night and have a stronghold on the life of the people there. Mandal’s grandfather had fished for a living; his uncle, a honey collector, had fallen prey to a tiger. Mandal’s father had settled for agriculture. Mandal and his brother had changed all that by going to college. Now Mandal works not just as a tourist guide but also a teacher at home. He has nearly 30 students coming home for “tuition”.

Mandal tutors us on how to recognize a high tide and a low. At low tide, the submerged trees and roots surface looking wet, muddy and grey. It is easy to guess, looking at them, how high a tide can be. Mandal points to a thin strip of land, less than a breadth of a road. It is an island in the making. The tide like an architect constantly erodes islands and creates new ones.

At Pakhirala, M V Krishna, our small launch for the next two days is already waiting to take us to Sajnekhali where we first have to seek the forest department permission to continue our travel through Sunderban. It is a much smaller boat than Sarbajaya with two decks; the lower deck has a couple of beds, and a kitchen and the upper, a few plastic chairs for us to sit. The best place, though, is the bow, which has room to stretch and experience an adrenaline rush. We reach Sajnekhali, and as we settle into our dormitory, the camp manager warns us against the Rufus monkeys, which hang about us looking for some quick bite. The manager, a young man from Darjeeling, residing alone in a small quarters in Sajnekhali lodge, is full of stories about but the tiger. One particular day, a tiger had been spotted by the lodge.

That evening the manager and two others decided to wait by the watch tower hoping for that rare glimpse. Hours went by and just as their patience was wearing away, the majestic being walked to the pond right ahead of them for a sip of unsalted water. “It was so close by. I knew we had to retreat. But that very moment the tiger raised its head and looked straight at me. It locked its eyes in mine, and I stood there completely hypnotised. Remember that is the way the Sunderban tiger decides on its victim. Once it locks its gaze on a prey, there is little chance of escape. No barrier can stop it after that. Suddenly somebody threw a stone and broke its concentration, and I was saved that day.” His tale traversing through suspense and exaggerated drama leaves us mesmerized.

A little later, we walk towards the watch tower and stare into the horizon. It is getting dark. The crocodile we saw earlier sitting like a sculpture on the pond bank is now playing hide and seek in the water. Next morning we set out early to Burir Dabri, an island on the India-Bangladesh border. Mandal has re-ignited our hope of seeing the elusive tiger on this island far far away from the maddening crowd. It is a good five hour ride to Burir Dabri; on the way we pass Marichjhapi, a Sunderban island made infamous by the 1979 killings.

Pointing towards the island, Mandal recalls how “overnight over 200 refugees from Bangladesh arrived and settled on the island and they were most self-sufficient; they even had doctors amidst them. They never ventured out of the island for anything. But the newly-elected Jyoti Basu government decided to uproot the refugees which took the form of police brutality and indiscriminate firing; not a single house was spared.” No one enters the island now, but Mandal tells us it still houses some remnants of that history which is hardly talked about presently. We pass Marichjhapi wondering about the ghosts that currently inhabit the island.

Many more islands go by and we catch glimpses of idols and other artifacts all hung in Bonbibi’s worship. At one stretch, the islands are far, far apart but Mandal tells us tigers can swim the distance. So, no matter how far the domestic animals and humans are, the tigers can still reach them with ease. Suddenly there is a magical moment – three Irrawaddy Dolphins frolic towards us and play hide and seek before disappearing completely leaving us madly questing after more magical moments. A wild boar family looks on as our launch wavers through a creek.

We reach Burir Dabri in the afternoon where a long canopy walk awaits us. The island apparently got its name from an old woman who sat all day chewing on her betel leaf. Standing on the watch tower, Mandal points out to the island across; it lies in Bangladesh. An imaginary line cuts across the waters separating the two nations. Finally we see something of the tiger; pug marks at least a couple of days old, Mandal exacts. At the reserve camp, a worker cautions us not to enter the Bonbibi shrine area with slippers. Fresh flowers adorn her doorstep. We return from Burir Dabri, having sighted a Brahminy kite, several fiddler crabs, flameback woodpeckers and mud skippers. On route, we stop by the bird sanctuary where plovers, red shanks, whimbrels and more unheedingly go about their business of pecking on the mud flats.

They scurry into the woods only when some tourists alight and walk through the slush greedily hoping for a close look. Mandal says such greed among tourists is far better than a complete lack of interest in the flora and fauna of Sunderban which he encounters very regularly. “They come in groups and all they want to do is drink and make merry.” True to his description, we meet one such inebriated group during the trip; they are loud, groggy and complaining that the tiger is nowhere to be seen.

The day has ended but not our thirst for the Sunderban tides and the next day we set out at the break of dawn on our jungle trail through narrow creeks. Mandal’s eagle eyes sight a brown-winged kingfisher; it is flaming orange and as huge as a pigeon and it is calling out to its partner on the opposite island. We only hear the other’s call back. No sooner Mandal is drawing our attention to a crocodile basking in the morning sun. It charges angrily into the water on hearing our launch. The noise we make is enough to send all the wild things into hiding. We may not see the tiger, but the tiger is watching our every move, Mandal dramatically lets in, adding how it is so much more intelligent than us.

Yet again his hawk-like eyes have spotted something unusual; pugmarks leading from the forest into the waters! He orders the man at the wheel, the owner of boat Krishna, to go closer to the island. “There were three tigers in all and we must have missed them by a few minutes, may be 8-10 minutes,” Mandal reveals. He is frantic, all so ready for a chase as he steers the launch to the opposite island. Just as he expected, the pugmarks start from the opposite bank and lead into the island. We have just missed seeing three tigers swim across the waters! Imagination is all we are left with as we retrace our way to Mandal’s island Dayapur, located opposite Sajnekhali. It is our last night before we return to Kolkata and we have decided to stay with Mandal at his house. As we walk on the river bund towards the village, we spot white and forest wag tails, rufous magpie and kingfishers. For some birds, living closer to human settlement has advantages. We hope to see the pied kingfisher which, like the tiger, has eluded us throughout our stay.

It is an idyllic island, with a pond by almost every house. There are ducks swimming, kids playing, villagers sipping tea over a chat or hurrying their livestock back into the house. Not all houses have electricity, those that do like Mandal’s run on solar power. Dayapur was chosen as a model village some years ago, Mandal says, pointing towards two wayside roads, one developed by the village panchayat and the other by the West Bengal government. The government’s initiative to provide solar lighting has apparently helped to keep the tigers at bay to an extent. As Mandal works on the kitchen chula, he recalls the days when cyclone Aila hit the islands in 2009 causing immense destruction.

The Sunderban waters that had rushed into their village and refused to subside for days, and there were bodies floating everywhere. Having witnessed death and destruction all around, his wife had gone into early labour that year. Their nearest medical aid is in Gosaba or Canning which are close yet not easy to reach, but for any medical emergency, Kolkata is the only option and it is a good three hours long and dreary journey. As we hear Mandal’s many stories, we wonder what it means to live in these islands. But it is home to Mandal and he is visibly proud of it; only recently he even managed to renovate his home with cement walls, a dream every villager staring into a cyclonic future cherishes for.

As we say goodbye to the Mandals next morning and make our way to Canning where suburban trains ply to Kolkata, it is obvious what is playing in our minds; we are secretly sure of returning to the land of the elusive tiger and so much more. It is a trick, we realize, that Sunderban has played on us by keeping the tiger out of sight. The net is cast and we are ready to grab the bait.

How to get to the destination:

Nearest airport: International Airport Kolkata. Sunderban is 112 km away from airport. Nearest railway station: Canning, 53 kms from Sealdah station, Kolkata. Road: Taxis and public transport buses ply from Kolkata to Canning and Sonakhali (100 kms).

The West Bengal Tourism Development Corporation (WBTDC) has special packages for Sunderban. The backpackers route:Public transport buses and shared taxis ply from Canning to Gosaba.At Gosaba take a cycle-rickshaw to Pakhirala. There are boats from Pakhirala to Sajnekhali where WBTDC has jungle lodges. For booking rooms, visit the WBTDC website. If you reach Sonakhali from Kolkata, there are boats to take you to Sajnekhali jungle lodge. Things to see: Unending sangams or confluences of rivers, mangroves with stilt and breathing roots, several bird species and animals including the Royal Bengal Tiger. Things to do: Remain silent as far as possible, especially on islands inhabited by animals. Carry a binocular and camera.

For more information: log into http://www.westbengaltourism.gov.in