“If I should have a daughter, instead of ‘Mom’, she’s gonna call me ‘Point B’, because that way she knows that no matter what happens, at least she can always find her way to me. And she’s going to learn that this life will hit you hard in the face, wait for you to get back up just so it can kick you in the stomach. But getting the wind knocked out of you is the only way to remind your lungs how much they like the taste of air. There is hurt, here, that cannot be fixed by Band-Aids or poetry.”

When American poet Sarah Kay performed this work, If I should have a daughter at TED in 2011, it went viral and struck a chord across the world. Kay is the founder of Project V.O.I.C.E. and uses ‘spoken word’ as a tool of personal and social commentary. All good poetry though should render itself to narration and today performance poetry is many things. It is meant for those who are intimidated by poetry and for those who just appreciate the drama and immediacy of having a writer read out her or his work a few breaths away.

Poetry is primarily performance and the concept of mushaira in Urdu poetry is also part performance and part narration. In the Mughal courts, entertaining one-upmanship sessions would unfold between Ibrahim Zauq and Mirza Ghalib. Today, performance poetry is theatre, activism, celebration of individuality and stuff that is not convenient to say or to hear but must be put out there.

Imtiaz Dharkar, one of the most recognised voices in Indian poetry came to Bangalore a few years ago with her book The Terrorist at My Table. And even though she read from it without theatrical interventions, her words bristled with gentle rage at the way imperialist forces subjugate micro cultures for the sake of politics, for oil, for profit.

In 2007, performance poet Aoife Mannix came to Ranga Shankara and brought with her the cadences of her Swedish, Irish, American, Canadian childhood. She was a young, passionate narrator of what identity means to a young woman whose soul is looking for a home with her name on it and her story resonated with every woman in the audience.

Her derision for war rings particularly true today and one recalls her recipe for a revolution without wars where, “bullets will bounce where they come from, leaving no scars, just a trail of jelly beans. Soldiers will only wear birthday suits. There will be free ice cream, refugees will party in the streets and then come home to, balloons and streamers, with suitcases bursting with all they have lost”.

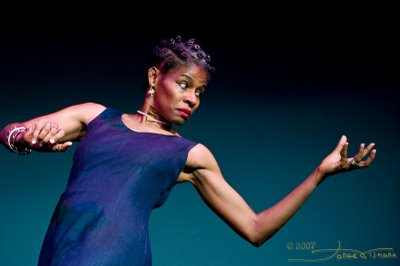

Indophile of American, Dominican descent Josefina Baez performs her works, Dominicanish and Comrade, Bliss Ain’t Playing, all over the world.

How powerful performance poetry can be is visible when Rafeef Ziadah, a Palestinian performance poet and human rights activist based in London, gives a voice to the living and dead for whom war is a continuum without a pause. Her poem We Teach Life, Sir recently took the Internet by a mild storm, bringing even apolitical people to tears. With great conviction and contained anger, she brought home the devastation of children and unarmed victims with words like,

“And these are not two equal sides: occupier and occupied.

And a hundred dead, two hundred dead, and a thousand dead.

Is anyone out there?

Will anyone listen?

I wish I could wail over their bodies.

I wish I could just run barefoot in every refugee camp and hold every child, cover their ears so they wouldn’t have to hear the sound of bombing for the rest of their life the way I do.

And let me just tell you, there’s nothing your UN resolutions have ever done about this.

And no sound-bite, no sound-bite I come up with, no matter how good my English gets, no sound-bite, no sound-bite, no sound-bite, no sound-bite will bring them back to life.”

Rafeef’s debut album is dedicated to, “Palestinian youth, who still fly kites in the face of F16 bombers, who still remember the names of their villages in Palestine and still hear the sound of Hadeel (cooing of pigeons) over Gaza.”

And you realise as you listen to her that sometimes poetry is not just performance or an agenda or entertainment but a little flame of defiance in a wasteland. A little reminder that though the world may be going to hell, there are poets out there who still stand up and say, “Stop”.

Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, Bangalore, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, an artist, a former RJ and a mother. She dreams of a cottage of her own that opens to a garden and where she can write more books, paint, listen to music and just be silent with her cats.

with

with