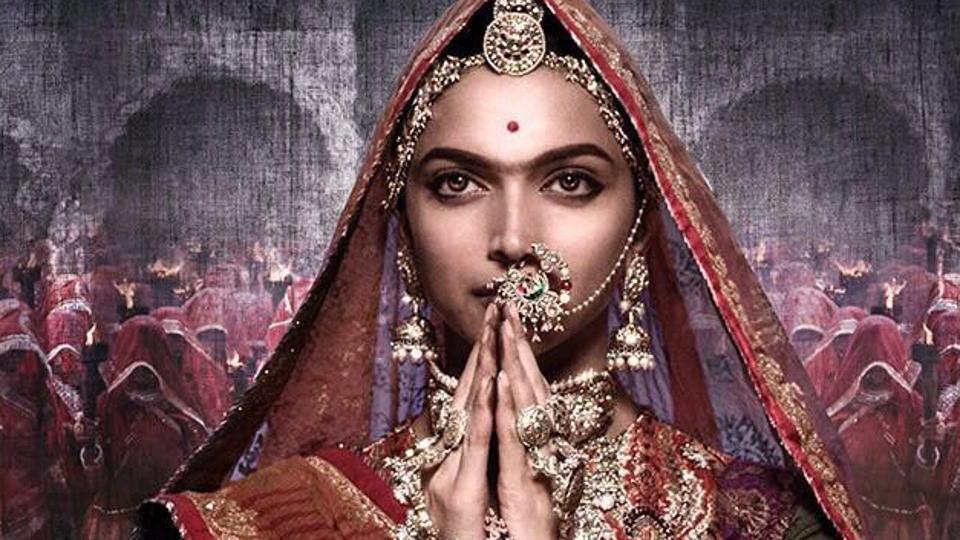

This could have been the tagline of Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmavati.

The difference is that in the first film, the hero is avenging himself by punishing the woman who broke his heart. He wants to teach her the difference between “pyaar” and “nafrat” and in Padmavati, the man waging a war is an invader trying to win a woman who can’t be his.

The first woman must be taught a lesson and be punished because she is bad.

The second one is so good that one man wants to conquer and punish her and another man fights for her to defend her. She is so good in fact that she chooses to commit “Jauhar” and jump into fire than be touched by the marauding invader with a Muslim flag and wolfish eating habits. Someone who just happens to be emblematic of the impure “invasion” of culture by “outsiders.”

**

But that is a story for another day and time. The narratives in both the films fall neatly into the stories that our cinema and society tell about women. The story of the impure and the pure woman, or as Bhansali calls his Padmavati, “the goddess queen.” Because God forbid that a woman should walk out of the identities we impose upon her.

She must be pure. She must suffer or how will she justify her existence in the world? The more she suffers, the nobler she gets.

The only free woman Bhansali ever created was in his first film Khamoshi. It flopped and he has since then learnt his lesson. Every subsequent heroine of his has suffered enormously to earn his respect and that of his viewers. Hum Dil De Chuke’s Nandini chooses conformity over love. Paro of course is the epitome of unfulfilled love. Black’s heroine has to make peace with one kiss that she steals from her old, unwilling teacher. And so on. Even Mastani who is a fearless warrior is punished in the end for her heedless desire to love a Maratha. But still love triumphs in some way in that narrative.

In Padmavati, the war being waged is not over love. But honour. Because THAT distinguishes a good woman from a bad one. That is why people came to beat Bhansali on his sets perhaps without knowing that though the film he is making is inspired from Malik Muhammad Jayasi’ s epic poem, it falls in line with the misogyny that continues to thrive today in the name of religion, culture, in cinema and in our society and on social media where trolls post rape threats to teach women about their “sabhayata.” Our law makers now decree that when a woman says ‘No,’ she really doesn’t mean it always. So yes, there is a war being waged against women. A war that robs them of any selfhood and volition except what story tellers and law makers and politicians and trolls and keepers of culture choose to give them be it closer home or in the US where the man who once boasted about assaulting women without their consent is now in charge of depriving them of adequate health care, reproductive rights, protection against assault in campuses and openly calls the mothers of protesting black athletes as “bitches.” .

Just as last year the Access Hollywood tape failed to dent Trump’s popularity, this year it is movie moghul Harvey Weinstein who is trying to protect his personal and professional equity after he was caught on tape telling a model that he was “used to ” making inappropriate advances and has been called out for sexual aggression by scores of women.

So try and wrap your head around this. Both Trump and Weinstein got away with predatorial behaviour because they were in positions of power and this rule applies to every situation in every context. If a man is powerful, he will get away. Woody Allen is still making films. Baba Ram Rahim suppressed the voices of his victims for years with his political clout .

**

Even men with no vestiges of power threaten and stalk women on social media for defying their narratives, be it political or religious. Also any woman who dares to talk about the unholy power equations in the entertainment industry is name called and shamed. And she either becomes a cautionary story like Jiah Khan. Or becomes fodder for polarising gossip and TRPs like Kangana Ranaut (who may or may not be speaking the truth but has at least started a debate about the behaviour of powerful cliques in the industry)

We refuse to discuss the genteel sexism of makers like Gulzar and Basu Bhattacharya (their cinema merits another article) or the open secrets in the industry about men who beat their women, and abuse and exploit new comers. Another disturbing element in all of this is the role that complicit women play. Women who know something is wrong but choose to align themselves with power rather than with other women. In an interview, activist Kamala Bhasin had once told me that patriarchy counts on women to uphold it too. So when Donna Karan who has dressed women to express their power for decades says that we can’t blame Weinstein because women today ask to be exploited, we know for sure that the face of patriarchy is gender fluid.

**

Because, predatorial power exists everywhere and even though it may not always be as obvious as Weinstein lurching at his victims in a bathrobe, some of us are remembering our own encounters with men looking for victims.

**

How do we change this? How do we tell new stories about women? How do we make power accountable? How do we learn to stand up for each other rather than being used as pawns against each other? How do we rewrite laws? How do we stop culture from being used as a whip to control and shame women?

How? I really don’t know but what gives me hope is that narratives can be changed.

It took two brave women to bring down the empire of Baba Ram Rahim. Look around you. In journalism, in colleges, on street corners, women are speaking up and challenging hegemonies of thought.

Gauri Lankesh was killed but it would be impossible to kill the rebellions she has sparked.

Yet, it would only be just to remember that when Gauri was killed, she was alone.

She was financially struggling. She was vulnerable. And nobody fought for her while she was alive.

That is what we need to change.

That. Before change outside of us begins to reshape stories about women and who they are.

So no, we don’t need a fictitious Goddess queen to aspire to.

We need more women like Gauri Lankesh till we reach a point where they are not perceived as a threat but can fight and win and live to tell their own tales.