“He was chewing on his paan, slowly and thinking. Thick jets of sticky, tobacco-mixed gob was swishing in his mouth. He felt as if his teeth were grinding his thoughts and blending them with his saliva.Maybe that was why he didn’t wish to spit out the gob of chewed-up paan.’’

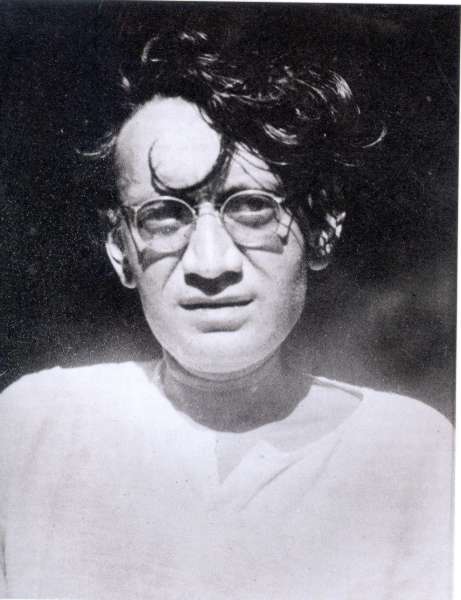

Muhammad Umar Memon’s translation of the essential Manto succeeds in achieving one thing. In animating the bead of sweat, the drop of saliva, the gob of tobacco and the taste of chewed up thoughts, the awry seams of threadbare lives, the itch of a Mange eaten dog, the smell of lust, the stench of hovels and the urgency of everything that was both sublime and putrid and part of Saadat Hasan Manto’s understanding of life and death. If there is any South Asian writer who understood the darkness and effulgence of the human spirit, it was Manto. As a writer, he was, as Suketu Mehta had noted once, or as Manto himself had observed, someone who “chased filth and not fragrance. Someone who chose dark labyrinths over the bright sun, the naked and the shameless over the modest, the bitter over the sweet, slush over clear brooks, tears over laughter.’’ Manto was, without seeming to be, one of the most empathetic writers ever because he looked where no one did. In the heart and soul of women dismissed as whores. In the anger and frustration and defeatism of female acting aspirants in the 40s being exploited or suppressed by men.

In Partition’s rape victims whose violation remains invisible to us till one of them is brought to a hospital a few inches away from death and meekly opens the string of her salwar and pushes it down automatically when the doctor looks at a closed window and says, “Open.”

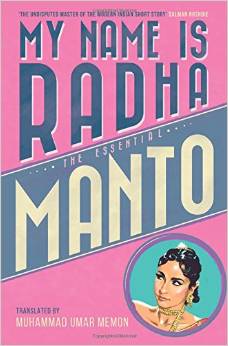

Memon picks stories from many of Manto’s collections for My Name is Radha (The Essential Manto) and his translation for most parts recreates the horror and the terrifying ordinariness of fringe lives. The grimy pathos of a sex worker’s life (Saugandhi) is brought home to us when we see her sprawled on her bed, “her bare arms splayed out like a bow-shaped rib of a kite that has come loose from its dew-drenched paper. The grainy flesh visible in her right armpit had acquired a blusih tint from frequent shaving and looked like a graft from the skin of a freshly plucked chicken.” This is Manto, translated or not. Not missing a thing. Consuming his characters body and soul and blood and pith till not just he but we are them. And so when Saugandhi prays to her gods, hides her money under a bed post and then in a fit of rage, kicks out a pretend lover with whom she fakes domesticity once in a while, we know why her world has come crashing down. It is because, even on a night when she was wearing her best saree and make up, a refined client was repelled by her. Her pride, for want of a better word, is wounded. Or perhaps her humanity is.

The book despite a few moments that don’t really get where Manto reached with his pen, brings to you the flesh and blood fervour of women like Neelam/ Radha who breaks past the reserve of an idealised star.

The man, a cross between Raj Kapoor and Dilip Kumar is dealing with his own demons by faking a filial bond with her while Manto, the eternal observer is watching the cat and mouse game between the two on a film set. The end of this almost primitive struggle between a woman who has been scorned with extreme kindness and a man who refuses to be tempted, is neither predictable, nor conclusive. But yes, the vamp Neelam finds a moment in this madness that connects her to truth and so she whispers at the end of it all, “My name is Radha.” Or was, we presume.

Manto died at the age of 43 but his stories are not just about his time or ours. They are about the stuff of pain, violation, loss and ugliness and a grain of mirth hidden even in tragedy. And so translations like this one will stay relevant, especially now when story telling is dispassionate and bloodless.

Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, a translator who recently interpreted Dominican poet Josefina Baez’s book Comrade Bliss Ain’t Playing in Hindi, an artist, a former Urdu RJ and a mother. She won an award for her writing/book from the Public Relations Council of India in association with Bangalore University, has written for a host of national and international magazines since 1994 on cinema, theatre, music, art, architecture and more, has exhibited her art in India and the US…and hopes to travel more and to grow more dimensions as a person. And to be restful, and alive in equal measure.

with

with

‘We had been robbed of everything on our way here, but by the grace of God we are now dealing in riches.”

The Master Of Bare Things —–

Well, anything that is banned reaallly interests me as a person. Therefore Manto had to be prey to my curious soul. He entered my life when ma’s friend brought her a book by Manto which we were not even supposed to even know the name of. Knowing ‘my reasons’ to what being prohibited was esp. in home I let Manto be. Ma eyed aunty for even handing it over in our knowing. Few years later, while away from home in Delhi, I had a hard bounded copy of ‘the case of exploding mangoes’ by M.Hanif when my dear roomie handed me her copy of recently launched book named Naked Voices, she being fairly familiar with my likes. And then began my real affair with Saddat Hussain Manto. Just one story past I realised the reasons of ma’s fret. You first have to get used to knowing truth only then one can come to terms with truth he likes to tell and particularly in the way he likes to. The society we are part of shuns to show-up that side.

Even in translation, the writings of Saadat Hasan Manto were blindingly good, my favs being Aatish Paray, Toba Tek Singh. Since then I have laid hands on many of his short stories.

His works stand out soulfully to the truncated and departed part of his suddenly ruptured world talking plainly about nostalgias’ of his fragmented Pakistan. With his works he stares blatantly on the jingoistic physics of both Indians’ and Pakistanis’ alike without imparting morals or being moral guru talking barefacedly about the chronicles of partition and the torments and banes millions of souls bore witness to. In spite of the crude words and brutal dwellings his narration bears, his stories inspires me, evokes me to be humane at the same time questioning humanity …!!! PARTITION sculpted the Manto everybody gets offended with, yet everybody recalls him for, his most loved works and even his untimely death. Partition forever lived in his dying soul. He took it upon himself to reveal the unsung stark naked truth.

Couple of weeks back, papa suggested me to read a column in some national daily by Zahida Hina titled “Main Manto-Ek Film”—a biographical on Manto acted and directed by Sarmad Khoosatand written by Shahid Naideem of Ajoka Theatre. Upon seeing ‘Manto’ in the title I knew why he wanted me to read that article, I being a Manto-Maniac…. It was about the recently realised film-Manto and more about Manto.

‘We had been robbed of everything on our way here, but by the grace of God we are now dealing in riches.”

The Master Of Bare Things —–

Well, anything that is banned reaallly interests me as a person. Therefore Manto had to be prey to my curious soul. He entered my life when ma’s friend brought her a book by Manto which we were not even supposed to even know the name of. Knowing ‘my reasons’ to what being prohibited was esp. in home I let Manto be. Ma eyed aunty for even handing it over in our knowing. Few years later, while away from home in Delhi, I had a hard bounded copy of ‘the case of exploding mangoes’ by M.Hanif when my dear roomie handed me her copy of recently launched book named Naked Voices, she being fairly familiar with my likes. And then began my real affair with Saddat Hussain Manto. Just one story past I realised the reasons of ma’s fret. You first have to get used to his knowing truth. The society we are part of shun to show-up that side. Even in translation, the writings of Saadat Hasan Manto were blindingly good, my favs being Aatish Paray, Toba Tek Singh. Since then I have laid hands on many of his short stories.

His works stand out soulfully to the truncated and departed part of his suddenly ruptured world talking plainly about nostalgias’ of his fragmented Pakistan. With his works he stares blatantly on the jingoistic physics of both Indians’ and Pakistanis’ alike without imparting morals or being moral guru talking barefacedly about the chronicles of partition and the torments and banes millions of souls bore witness to. In spite of the crude words and brutal dwellings his narration bears, his stories inspires me, evokes me to be humane at the same time questioning humanity …!!! PARTITION sculpted the Manto everybody gets offended with, yet everybody recalls him for, his most loved works and even his untimely death. Partition forever lived in his dying soul. He took it upon himself to reveal the unsung stark naked truth.

Couple of weeks back, papa suggested me to read a column in some national daily by Zahida Hina titled “Main Manto-Ek Film”—a biographical on Manto acted and directed by Sarmad Khoosatand written by Shahid Naideem of Ajoka Theatre. Upon seeing ‘Manto’ in the title I knew why he wanted me to read that article, I being a Manto-Maniac…. It was about the recently realised film-Manto and more about Manto.

Really apologetic about the comment-error made on my part… thw whole comment somehow got double printed… 🙁