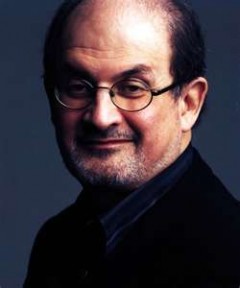

Who is afraid of Salman Rushdie? The fundmentalists? Politicians playing minority politics? Ordinary readers and writers who just want to read and write without any threat to their life and limb at the Jaipur Literary Festival? Alright so, it is absolutely safe for a cop in a police station in Punjab to beat a woman to pulp but not safe for authors to read from The Satanic Verses in public? It is okay for the widows in Benaras to waste away in penury and die of isolation and neglect but not okay for Deepa Mehta to make a film about it in India? It is okay for baby girls to be killed, rapes to become commonplace but not okay for a lesbian relationship to play out in a film like Fire?

Riots are okay, genocide in small measures is not too hard to swallow but films like Black Friday and Parzania must be censored and banned or obstructed from reaching the people they are meant for? Okay, let us try and understand something. So if you are a muslim, you cannot paint Hindu Gods and Goddesses? If you are a muslim, you cannot write a book like The Satanic Verses? If you are a woman and belong to a certain gotra in a certain village in Haryana or Punjab, you cannot fall in love or marry a man of your choice? Censorship of voices is not new in India. Some of us lived through the dark days of Emergency and then grew up to understand that the most deeply rooted censorship diktats are the ones that are bred in our identity. The ones we are constantly aware of even though they are not written down any where.

Why are we surprised that governments across the world, even in some of the (supposedly) most democratic countries, are itching to clamp down on the Internet? In India, it was expected because for the first time since independence, in 2011, large masses of people galvanised by shared anger and fuelled to some extent by Internet activism, took to the streets to ask for change and show their leaders that their silence could not be taken for granted anymore.

It is also not surprising that many thought leaders in mainstream media came after Anna Hazare rather than the powers he was targetting because he for all his faults, represented the voice that had connected with something dormant, something bitterly angry and something that could potentially shake entrenched powers-that-be. Main stream media is a tame beast now. It is the voices of bloggers and those on social networking sites that must be silenced.

Politics for most parts has been protected from stirrings of public dissent in India. Art, cinema, literature however have been compromised again and again by short term agendas. Remember Chandramohan Srilamantula? Five days in jail and the poor boy did not even know what his crime was. He did not break any public property. He did not burn down anyone’s house. He did not molest any women or kill in the name of his favourite God. Or deal in illegal arms. Or drive over pavement dwellers in drunken stupor. Yet, he was hauled away in full public view a few years ago like a petty thief and locked up because he painted something that offended what are now fast gaining currency as as “religious sentiments.’’ Art exists and is debated about in an evolved society. Not in one where even fundamental human rights are held hostage.

Chandramohan was and is a symbol of everyone who does not count in India. Artists, filmmakers and voices of dissent do not matter. What can artists and writers contribute anyway? They won’t pick up arms to attack anyone. They won’t buy into the argument that the State and the country will progress only if they become totalitarian. Ofcourse Chandramohan does not count. Neither did Husain. Nor does Rushdie or any voice that does not shout slogans because now only herds with weapons are heard.

If you think hard however, the issue at stake in Chandramohan’s or Husain’s story are not Hindu Gods and Goddesses or their nudity. It is not about what Rushdie wrote or did not in Satanic Verses. The issue is whether some people have more freedom than others.

But were we always like this or was there a time when artistic and literary freedoms were sacrosanct things? Husain was banished from India for painting spirituality in a certain way that was considered disrespectful but the human body has never been a thing of shame in Hindu religion. It is a symbol of awakened spirit. That is why the yoni and the lingam are worshipped. Kama, the God of love has special place in our mythology. The Raas Lila celebrates with music and dance, the merging of the spirit with the body. Shringar Rasa is a beautiful overture to spiritual romance in Natya Shastra. Vatyayana is still teaching the world to make love. Imagine if he was born in today’s time?

Kamasutra would have been burnt and held up as a symbol of western civilization corrupting our culture. Meera would have been vilified as an amoral woman going against our sabhyata for her impure love for a God who must be worshipped but never considered human enough to be a lover or a spouse. Sufi saints would have been stoned too for daring to sing that God is their beloved. Waris Shah would have been banned for writing about the passion of Heer and Ranjha because how can two lovers be praised for not conforming to society?

Thank God Amrita Preetam died when she did. Her books would been torn as they had many impure ideas about a woman’s sexual suppression and they would have corrupted our collective maryada and its innocence. Punjabi poet Shiv Kumar Batalwi would have been humiliated for saying in his most famous poem that he would rather have a priest pour wine in his lips than Ganga Jal at the time of his death. Harivansh Rai Bachchan would have been negated for saying that while religion separates people, a Madhushala brings them together. Imagine if someone had dared to build a modern version of sensuous cave sculptures?

Had the moral police telling us now what to paint and what to write, existed in the past, none of our scriptures would have been written. Many of our temples would not have been built and our literature would have been robbed of some of its most evocative works. The irony is that the intolerant amongst us, no matter of which religion, say that their beliefs are threatened by painters and filmmakers in the present when they should be looking at the past to understand that violent perpetrators of morality have never mattered to a culture known for its richness of thought and openness of spirit. It is a past, that even they, with all their shining new weapons cannot erase or deface.

Note: Parts of this article were taken from a column that was written by the author for The New Indian Express many years ago.

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight (http://www.flipkart.com/b/books/perfect-eight-reema-moudgil-book-9380032870?affid=unboxedwri )