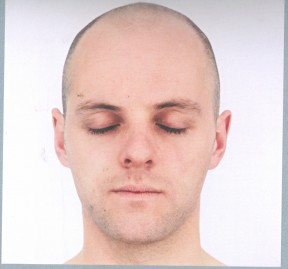

It’s a close up of a man’s face – the eyes are closed, a slight smile hovers around the lips and the stark-white background brings into sharp focus every detail of a shaven head. The work is self-referential and focuses on the conceptual presentation of self portraiture.

It’s a close up of a man’s face – the eyes are closed, a slight smile hovers around the lips and the stark-white background brings into sharp focus every detail of a shaven head. The work is self-referential and focuses on the conceptual presentation of self portraiture. To most of us, this may seem like a simple picture but the photograph, titled Portrait of Something I’ll Never See by Gavin Turk, has inspired the travelling show of contemporary photographs from the Victoria and Albert Museum collection which opened last month at the Capital’s National Gallery of Modern Art.

To most of us, this may seem like a simple picture but the photograph, titled Portrait of Something I’ll Never See by Gavin Turk, has inspired the travelling show of contemporary photographs from the Victoria and Albert Museum collection which opened last month at the Capital’s National Gallery of Modern Art.

Conceptual photography has been explored by several Indian artists as well. Veterans like Rameshwar Broota and Diwan Manna have used surreal imagery as a divergence to the notion of photography as a ‘slice of reality’. The photographs in the NGMA show – which will then travel to Bangalore and Hyderabad – also fall into this category. Says Martin Barnes, Curator of photography at V&A: “This changing perspective of photographers, where they find a purpose for their craft that goes beyond the traditional function of documentation, is one reason for the rising popularity of contemporary photography. Works of contemporary photographers have become aligned with the concerns of contemporary fine art practice, focussing on the illustration of an idea rather than on demonstration of skill or mere aesthetic pleasure.”

Hence, you can’t help but be moved by the dreamlike quality in Andrew Lock’s abandoned room with an empty bed – the only light being a lurid green glow coming from an un-curtained window. The image is from his famous Orchard Park series – the main leitmotif is abandoned furniture – where Lock projects the image onto painted phosphorescent surfaces, creating an unfixed but luminous after-image.

Creating an illusion is the hallmark of Cindy Sherman’s work as well. She uses masks and disguises to pose questions about female identity and gender stereotyping. Like Sherman, who dresses up like an agricultural labourer in a reference to the American Revolution – several other photographers use portraiture as a take-off point. Hellen Van Meene, known for her portraits especially of young girls, reflects on the awkward beauty of adolescence. All her photographs are on a small and intimate scale and use available light, without flash or artificial reflection.

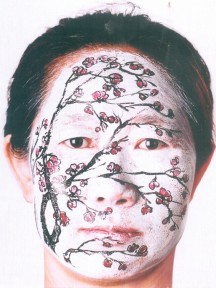

Another work that stands out for its sheer simplicity of composition is Huang Yang’s Plum from the series Face. In this series of four works, Yang paints the faces of models with images of plants closely associated with Chinese culture. Though painted on the face, the plants are enlivened by the model’s eyes, creating what Yang describes as ‘mutual interaction between the spirit of the plant and of the model”.

While the main focus of the show is on conceptual photography – some other eye-catchers are the surreal shapes of Olga Chernysheva’s Fishermen Plants which are photographs of Russian fishermen wrapped in plastic to keep out the bitter cold, Chris McCaw’s Sunburn which looks like a needle on clear glass but is actually the effect of sunlight scorching a negative – it highlights trends in fashion photography and landscapes as well.

In two large sized untitled photographs of a green landscape with only a trace of a train track to break the monotony, Andrew Cross documents freight routes as a kind of meditation about where transport links go and what cargo is carried on them. A keen train-spotter-turned-artist, Cross says that railway landscapes are similar even in different countries. “With this diptych, I have converged an American track disappearing into the woods to reappear as a German one, disintegrating boundaries in one sense,” he says.

And then there is leading fashion photographer Tim Walker’s What’s in Vogue. With a style that is as lavish as fantastical, Walker constructs an elaborate stage like setting and uses oversized props to play with scale to reiterate that “fashion photography can be concerned as much with dreams as with clothes”.

Transcending reality while capturing its essence is best summed up in American photo-journalist Dorothy Lange’s words: “While perhaps there is a province in which a photograph can tell us nothing more than what we see with our own eyes, there is another in which it proves to us how little our eyes permit us to see!”