‘How do you cope with being housebound?’ he asks.

‘The world is suddenly very small. There are many things that don’t exist in my world: other people’s brightly lit living rooms, tourists asking the way, clothes wet from rain, stolen bikes, dropped ice-cream cones melting on hot asphalt, maypoles. Disputes over parking spaces, meadows of flowers, children’s chalk drawings on pavements, church bells. Walking along a street, seeing someone you like the look of, smiling at him and watching him smile back. The moment when you find out that a new, promising-looking restaurant has opened on the premises that have been empty for long.”

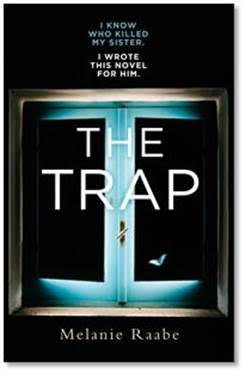

It’s no surprise that Melanie Raabe won the Stuttgarter Krimipreis (Stuttgart Crime Prize) for best crime debut of the year for her novel, The Trap. But it is not the story that makes the book the experience that it is. From the opening line, “I am not of this world, ” we are dunked into the dark, viscous inner world of writer Linda Conrad who is the survivor of a devastating family tragedy that has isolated her from the rest of the world for over 12 years, branded her mind with the fleeting glimpse of her younger sister’s murderer, made her chronically anxious, depressive and imprisoned her in a house where she now repeatedly relives the horror of the night that changed her life and also pieces together a story that will lure the murderer, now a respected journalist, back into a trap.

There is nothing about the plot that we ostensibly don’t know about beforehand or so we think but it is the way we live with Linda in her head, smelling and feeling the sticky blood seep through the membranes dividing the present from the past, and sensing a black chasm beneath our feet beginning to yawn that makes this book almost an alternate reality we can’t run away from.

Linda’s wistfulness for the life she can no longer step into is what really brings the extent of her loss home to us because we don’t just see the nuts and bolts of a sudden tragedy but what it does to its survivors who flit between guilt, loss, self loathing, anger, hopelessness and sudden flashes of light at the end of a very long tunnel.

It is when Linda begins to write her story in a novel and the present and the past collide that things get really interesting. Linda creates Sophie, her mirror image in the novel and as she begins to revisit memories, a lot of debri floats up and when the confrontation with the murderer happens, Linda is forced to also confront the past in a new light. Did she really see the murderer? Did he really murder Anna? Or was Linda herself trying to suppress a particularly horrifying memory? Was the trap she was creating for the murderer, in fact really meant for her?

What about the detective she had fallen for in the days following the murder? And what if Anna was not a pristine, infallible memory but flawed and vicious? It is the way the author adds layers of memory, snapshots from the past and the spasms of unhealed anger and raw pain that make the book richer than any crime novel has a right to be. Film rights to the novel have been acquired by TriStar Pictures but it is unlikely that the film will capture the almost literary quality of some of the chapters.

There are weak passages too. Some of the exchange between the supposed murderer and Linda especially in the latter part of the book appears a bit stilted as for the first time, the book strays outside Linda’s mind, beyond her imagined terror into a reality that somehow feels more cinematic than real. But this book checks almost all the boxes required for a crime read that does not leave you feeling empty once the last bullet has been fired. Imogen Taylor’s translation of Melanie’s German manuscript is pitch perfect. This is a book you will want to read again and again for lines like these,

‘At first, I think I am imagining things when the stars seem to shine paler and the sky begins to change colour. But then I hear the birds through the window. They start up as if an invisible conductor had signalled to them with a raised baton. Then I know the sun is rising. It is a miracle. That we exist at all. That the earth exists and the sun and the stars exist and that I can sit here and feel all this. If this is possible, anything is possible.’

(The Trap by Melanie Rabbe, published by Pan Macmillan, Price: Rs 399)

Reema Moudgil is the editor and co-founder of Unboxed Writers, the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, a translator who recently interpreted Dominican poet Josefina Baez’s book Comrade Bliss Ain’t Playing in Hindi, an RJ and an artist who has exhibited her work in India and the US and is now retailing some of her art at http://paintcollar.com/reema. She won an award for her writing/book from the Public Relations Council of India in association with Bangalore University, has written for a host of national and international magazines since 1994 on cinema, theatre, music, art, architecture and more. She hopes to travel more and to grow more dimensions as a person. And to be restful, and alive in equal measure.