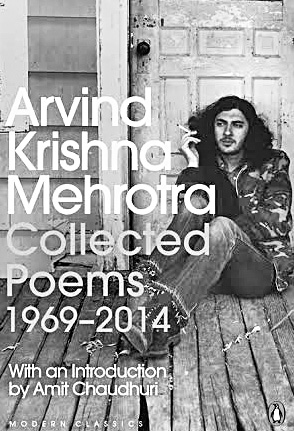

A picture of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, taken possibly in the 1960s, is on the cover of his latest anthology. His curly, unruly hair tumbles down his combat jacket. His jeans are frayed and with his boots making a statement all on their own, he looks like a cross between Che and George Harrison. This image, in a way, is much like the hard-to-define poetry Arvind has been writing from the 60s.

The latest anthology from Penguin, Arvind Krishna Mehrotra: Collected Poems (1969-2014), is a monumental work as it not just tries to encapsulate Arvind’s contribution to Indian poetry but also includes his translations of songs of Kabir and of the works of Hindi and regional poets.

In a long and insightful introduction, author Amit Chaudhury describes the anthology as the moment in Arvind’s poetry when “the speaker is caught looking at a mirror.” In one of his poems, Arvind writes:

“Sometimes,

In unwiped bathroom

mirrors

He sees all three faces

Looking at him:

His own,

The grey-haired man’s,

Whose life policy has matured,

And the mocking youth’s,

Who paid the first premium.”

In his introduction, Chaudhury tries to get to the taproot of what makes up Arvind’s poetry.

The sense of life filtered by an instant and sometimes, many lifetimes that show us who we were and are now, with all our losses, with mud on our shoes, dust in our eyes but almost always bereft of cogent, neat explanations about why things unfold the way they do. And the magic of everydayness that he captures like an impressionist painter. He writes:

“Small birds

chittering on the roof,

The ice-cream cart going by,

The leaves silvery in the light,

Never ceases to surprise.”

It was perhaps Eliot’s The Love Song of J Alfred Prufrock that altered a very young Arvind’s relationship with poetry. He began to want to write seriously and also realised that he too needed to find a vocabulary that went beyond the poetic idioms taught in Indian universities.

Like Eliot, for Arvind, the blending of real and surreal opened a door to a place where expression was not bound by romantic poetic conventions.

As Arvind asks, “How do you write about an uncle in a wheelchair in the language of skylarks and nightingales?” And in his poetry, you do not see the divide between the English and the vernacular, the universal and the local. Sample this poem about Ghalib where he paints with great pathos the story of impoverished greatness:

“His eyesight failed him,

But in his soldier’s hands,

Still like a sword,

Was the mirror of couplets.

By every post came

Friends’ verses to correct,

But his rosary chain

Was a string of debts.”

There is also a sense of intense loss that speaks of the work which is devastating, also because it is never just his loss but ours too. In a poem called Machete, he writes:

“A few blows of

the machete

And the young tree

Lay sprawled on the ground.

Dragging it across the yard,

I almost didn’t see the nest,

Its leaves joined as firmly

As bricks. It looked warm,

Habitable, like the house

I entered

To put away the machete

In a table drawer, muttering

‘Sorry bird’ to no one

in particular

As I did so.”

Also wrenchingly beautiful are his translations and his connection with poets who had nothing common with him and yet drew from the same well of life, from stimuli experienced, imagined, the stir of inspiration,

the imprint of hurt, the sunshine of wonder.

Sample his translation of Suryakant Tripathi Nirala’s famous Hindi poem Woh Todti Patthar, about a woman breaking stones for a living on a hot summer day in Allahabad.

“The sun climbed the sky.

The height of summer.

Blinding heat…and

the luu blowing hard,

Scorching everything in its path.

The earth under the feet

Like burning cotton wool,

The air filled with dust and sparks.

It was almost noon,

And she was still breaking stones.”

Arvind was the child of Partition but in his work, he has found indivisible connections that are subterranean and obvious — connections between far-flung realities, between languages, between poets and men, man and the earth, pain and rejuvenation.

This book must be savoured one word, one phrase, one poem at a time and then revisited again and again because just one reading does not begin to reveal the layers, seasons, histories and life stories it encompasses.

with

with