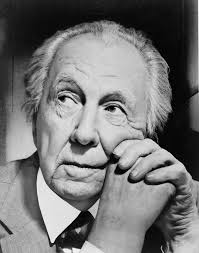

An article on Frank Lloyd Wright on smithsonian.com summed up his work in one perfect sentence, “He was there first.” Wright explored the word ‘organic’ as early as 1908 and unlocked architecture and set it free from conventional notions of what a building was supposed to be. He made us see what a building could be.

In the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York for instance, he literally turned the idea of an art institution on its head and created a seashell like spiralling space that was as much a work of art as a showcase for art. In a stunning co-incidence, Wright’s 16-year old struggle to build this structure against all criticism was mirrored in Ayn Rand’s classic The Fountainhead where architect Howard Roark is given a similar brief to build a “temple to the spirit” but is obstructed at every step.

**

What was visible in the final result in this structure as in everything that Wright built was the blending of individual aspiration with a sense of community and the credo, “Every building is a missionary.” Of truth and integrity and the idea that form must follow function but also that sometimes form can redefine function as well or meld into function completely.

**

For him organic architecture was about serving the whole of life, “holding no ‘traditions’.. nor cherishing any preconceived form fixing upon us either past, present or future, but—instead—exalting the simple laws of common sense..” For him organic meant natural buildings knitted to their environment in a close relationship. And respecting steel as steel, wood as wood, brick as brick and glass as glass where one material cannot serve the function of another. It also meant that every building had to be designed to serve a purpose rather than to mimic iconic architectural idioms. So a house and a temple and an office building had to be designed in keeping with their purpose and not fake Greek or Roman facades. To him, organic also meant defiantly ‘contemporary’ but at the same time respectful to the timelessness of nature. He believed the site and not repetitive styles should decide the character of a building.

Today he more than any other American architect is part of mainstream design trends and is at the heart of a movement addressing the global need for organic buildings. He passed away in 1959 but his influence grows more and more potent with designers, architects and consumers revisiting his Prairie style homes, his low slung residential spaces with their extended terraces and cantilevered roofs, overhangs, geometric lines, his use of materials that rendered white-washing and painting needless and an obvious connection between the outside and the inside. He aspired to be not the “architect of structures but of space.”

Many of his buildings including homes like Fallingwaters (Constructed over a 30-foot waterfall and considered to be the best all-time work in American architecture) are today tourist attractions and the smallest of homes designed by him reveal his attention to detail. He was obsessed about getting everything right including furniture, rugs, electric fittings and pioneered custom-made furniture and fittings. Who is to say that this passion was not genetic considering his mother had decided even before he was born that her first-born would design buildings! She covered the walls of his nursery with engravings of cathedrals and gave him educational blocks as an infant to play around with. While playing with the smooth, tactile cubical, spherical and rectangular blocks, Wright learnt what geometry could build and every structure he built as an adult drew from this childhood memory.

**

Wright was born in 1867 and saw America evolve into a modern, industrialized giant flexing its muscles and matched the industrial revolution with architecture that looked towards the future rather than the past. He discarded design with historic baggage and made it individual. His buildings had a spirited sense of self and he once said, “ What is architecture anyway? Is it the vast collection of the various buildings which have been built to please the varying tastes of the various lords of mankind? I think not. No, I know that architecture is life; or at least it is life itself taking form and therefore it is the truest record of life as it was lived in the world yesterday, as it is lived today or ever will be lived….”

**

Reema Moudgil has been writing for magazines and newspapers on art, cinema, issues, architecture and more since 1994, is an RJ, hosts a daily Ghazal show, runs unboxed writers, is the editor of Chicken Soup for The Indian Woman’s soul, the author of Perfect Eight (http://www.flipkart.com/perfect-eight-9380032870/p/itmdf87fpkhszfkb?pid=9789380032870&_l=A0vO9n9FWsBsMJKAKw47rw–&_r=dyRavyz2qKxOF7Yuc ) and an artist.

www.unboxedwriters.com

http://www.thehindubusinessline.in/life/2010/06/11/stories/2010061150130400.htm