Whenever photographer Clare Arni steps on Bangalore’s MG Road, young vendors of cliches flock around her, mistaking her for a foreigner. The moment she starts chatting them up in mellifluous Kannada, they realise their mistake. Only an Indian can speak an Indian language with a complete understanding of local particularities and without a trace of self-consciousness. Her white skin not withstanding.

It is not just the Indians who mistake her for a foreigner. Some foreigners do too. She shared recently with a grin that she is treated like “one of us” till they realise that she does not look at India with occasionally indulgent, frequently derisive or painfully patient gaze. “I don’t laugh at Indian English or funny signboards,” she says so they don’t know what to make of her. In the six books that she has done on India, the innumerable exhibitions of her work in India and abroad, what shines through is her complete identification with the country that she now calls hers and her belief that it is not just the Geography of a place or its visible eccentricities that define it. Not its garbage, its chaos, its non working components but its essence that breathes in its living culture, its crafts, music, cinema, the creativity and resourcefulness of its people. Her work is respectful to India. So is she.

I first saw her complete empathy with all that India is during a shoot when I accompanied her to the edge of Tamil Nadu. I was aware of her vast body of work as a top notch photographer from a respectful distance but was meeting her for the first time. During the long trip, while I just saw the landscape, she saw ethnic architectural idioms and the remains of a fast vanishing civilisation. She identified water bodies, deities, temples, history. At the alternate lifestyle commune we were to cover, she went with bare feet across beams and up a bamboo ladder in an unfinished house, carrying her tripod and camera without a hint of discomfort. She ate the organic produce in the kitchen, sitting cross legged and in all the work we did together subsequently, I found her reacting to buildings and people as if they belonged to her and she belonged to them. She does not judge or take anything for granted and values every experience and collects new ones hungrily.

She first came to India as a six-year-old girl and her earliest memories of India are of life in a palatial bungalow (now a star hotel) in Madurai. Her father was a highly placed executive and she remembers growing increasingly close to an Indian nanny who perhaps taught her to see India with Indian eyes. She was in India till she turned 13, then went to England to finish her education and came back at the age of 21 and married into an Indian family.

It was around this time, that she realised, she was not like tourists in India who came here to survive it, find God or just to ‘do’ places. She says, “There are those who think of India as an ‘assault course’ and say, ‘I survived India, the diarrhea, the malaria, the dirty toilets.’ Then there are the spiritual tourists who say, ‘I had the Buddha experience in Bodhgaya and now I will go find Krishna in Brindavan.’ There are those who smoke pot and those who just travel but the prejudices are the same, by-and-large. Many laugh at India, find it hysterical and funny and joke about the misspellings and the sign boards. They generalise about `these Indians,’ and I can’t relate to this even though am expected to because I look like them. My soul is Indian. India is in my blood stream. I grew up here. I feel a spiritual tugging in a Tamilian temple, not in a European church. My comfort food is rasam, not mashed potatoes.”

She continues, “India is a complex reality..it has such a great amount of living culture and that is what I document in my work. I have a great deal of respect for the fact that in India, heritage is still a reality. It saddens me that so much of it is going. Modernity and tradition have co-existed in India and they can continue to.”

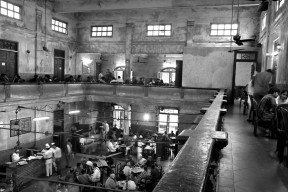

Clare has been for years now, passionately and with deep affection, documenting disappearing professions that the new India has no place for. Poster painters, bhishtis, calligraphers and more have found immortality in her works and she calls herself a documentary photographer by choice though her commercial architectural photography is what sustains her and captures the other India of affluent homes and cutting edge architecture. In one of her recent shows about disappearing professions, someone came upto her in tears because even without saying a word, the photographs had captured a sense of loss and a slice of what India once had in abundance.

Thriving, breathing, whimsical, not necessarily classical micro cultures. Unique. Complete. Self-sufficient. What she captures unfailingly in her work is a sense of truth, not so much the technique of her craft but the meaning of a moment. A place. Or a person like Meera (below), a Belgian woman with an Indian soul whom she discovered in Hampi, living happily like a hermit. And did a series of striking photographs with her.

Her love affair with India as a photographer began in 1984. She was teaching herself to do interesting things with the camera and got interesting work too that ranged from architectural photography to fashion to people to race horses! “What I love about my job is that each experience is new and unrepeatable,” she says and recalls how she strapped her three-month-old son to her back and went tracing the course of the Cauveri river from beginning to end. “I had an old Maruti 800, lived on a budget in seedy hotels for three months but it was one of the best trips of my life,” she recalls.

Her first book Eternal Kaveri came from that experience. Since then she has been to places as far flung as Peru, Afghanistan, and Myanmar and has been published by Thames and Hudson, Phaidon, Dorling Kindersley and Blue Guides. Her architectural work has featured in books of giants like Charles Correa, BV Doshi and Geoffrey Bawa. Her recent works have been published in Tatler (UK), Abitaré (Italy), The Harvard Design Magazine as well as Outlook Traveller, Namaste, Housecalls, Better Interiors and Inside Outside. Last year she completed a photo documentary on the works of a German aid agency in some of the most inaccessible regions of India and is currently working on several books documenting the cultural heritage of India.

But what gives her most pleasure is the intimate conversation she strikes with a space, a subject, with her camera and captures something only she can see. She says, “I am not a nostalgic person. I know, change is inevitable. But it can exist without destroying what was. If the spirit of India can survive everything time has thrown at it, then why can’t its visible culture? Why must old go to make way for new? With more empathetic conservation laws, we can preserve what is left.”

And when she says that, you know that hers is the voice of an insider who is part of the joy, the pain, the loss and the sense of pride that is India.

More about her on http://www.clarearni.com/

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight (http://www.flipkart.com/b/books/perfect-eight-reema-moudgil-book-9380032870?affid=unboxedwri )