Acclaimed author of The Dollmakers’ Island, Anu Kumar brings a treat for the readers of Unboxed Writers in the form of an unpublished novella that will be carried in nine parts. Here is a brief introduction. Three generations of a family have maintained a hotel that suddenly finds itself close to a new boundary line when India and Pakistan are partitioned. And as guests become witness to the drama that plays out on the border, little do they realize the drama unfolding within the hotel precincts itself : a grandfather who is a war veteran, a love affair, a friendship with a British officer who himself turns strangely senile; a disinterested father who develops a maniacal obsession with the hotel and then the narrator grandson whose love for melodrama has tragic consequences. In this surreal story, real life borders mingle with borders between what is real and what could be almost so.

This is part four of the long tale…

Father and Me

Because of the border that came up just five kms from the hotel, there were more soldiers and armymen who now frequented the hotel. There were also a couple of newspapermen I remember meeting in the dining hall. Father got specially renovated, the open verandah on the second floor. He removed all the lounge chairs, the hammocks, on which only a few years back, people had relaxed, feeling the breeze gentle around them. He had the place fitted with sleek looking telescopes and bucket shaped plastic chairs, so people could watch the action on the border. He also promised other adventure. Real ghosts, he told scared looking children and young teenagers who struck up a false bravado at his words. The old chef, someone from Burma, who my grandfather had rescued as a prisoner of war, said this was true.

So many people killed just trying to get across a safe line. It made lines of divisions come up in people’s hearts and overnight, people you had knew for decades became enemies. The women, he said, we don’t know what happened to some of them. But that night, we heard the splashes, a heavier, more deliberate sound, than that of an empty bucket hitting water. He pushed shaking fingers into his ears.

“The sahib,” said the old cook about my father,“he put the music on very loud then, to drown out these other noises. And then talked of the speech Nehru had made of a country being born again. That year he gave us a good bonus in Diwali. The hotel was more brightly lit up than ever before as it was the first year of a new period. But the lights showed up more strongly because there was darkness everywhere else. Across the new border, on the other side of the new fence, they lit a few fires maliciously trying to outdo us, but they soon flickered out. Even the wind, it seemed was on our side.”

The old chef wiped his hands on his apron, as if he had had enough of his rambling reminiscences,“Your father said that come what may, the hotel would always run. Your grandfather too was determined like that, but somehow things were different then. Now, it is like the hotel has become a living person who has to be kept alive at all costs.”

He laughed embarrassedly,“I am sorry. I spoke without thinking.”

And I was anxious to put him at ease,“No, you have been here for a long time. This hotel is yours too.”

I don’t know how father got to hear of this exchange but a few mornings later, I was summoned to his office. I spent most of my holidays, glued to the telescope, never tiring of the distant blobs that came to life before my very eyes, transformed by a tiny magical piece of glass. They seemed like figures in a puppet play, playing out their roles, with a sometimes exaggerated fierceness. It was that fence, an artificially created, manmade thing, that turned them into such ferocious creatures, people to be feared. I made my way to see father reluctantly, passing grandfather’s bust in the hall, noting how well it had caught his appraising look by the simple artifice of a raised eyebrow. Father, would tell me not to waste my time. To be involved in more serious things.

He did but for reasons that took me by surprise,“I told you not to believe in his stories. He is old and passing you war stories that he had heard in Burma. Such things did not happen here. You should not encourage them, maintain a distance, else you will never get them to work.”

The tension of being close to the border helped the business. There were always army men visiting, sometimes with their families, just to show them some action. I remember the old brigadier, a less decrepit version of Robertson sitting in one of those bucket chairs, specially lined with a cushion for him, clapping his hands and calling for some entertainment. And instantly, just as the last of his three claps resounded, the soldiers with him fired a volley of shots into the air. We heard the sound echo as it looked for a way out amidst the emptiness rolling away everywhere and then came back futilely. As it settled into the deadly silence, there was a fusillade of shots farther away. Angry, defiant and sarcastic in tone. It was the enemy across the border. The brigadier settled back in his chair, nursing his whisky, a blissful smile on his face.

The daily tension, varying in its doses, served the hotel well. I remember the manner in which the word spread, of the hotel’s unique charms. It promises real action, said everyone. I remember the banners that soon came up in parts of the highway that wound up north to Shimla and even south to Delhi and then further down Jaipur. There was grandfather pointing his gun straight at me and at the words that unfurled proudly beneath, speckled with red dots. The Hunter’s Lodge, since 1946, witness to history and to the present.

Its good advertisement, said my father when I mentioned the posters to him. Grandfather’s bust looked straight back at us, looking as stern as he always did. The hotel has had more guests now than ever before, even during your grandfather’s lifetime. He would have approved. He said it with lot of aplomb, success had brought in him a certain heartiness of behaviour. I looked for a long time up at grandfather’s photos, and convinced myself that he would have appreciated the changes.

Grandfather knew when it was time to let go, and he would have wanted the hotel to succeed. He would have got used to the changes – the shutting down of the open air tandoor, the stables, the enforced retirement of the old servants, especially my confidante, the Burmese chef. He would have nodded at the renovations – the huge ovens in the kitchen, the pruning down of the menu to serve only the Mughlai food, and the border tours.

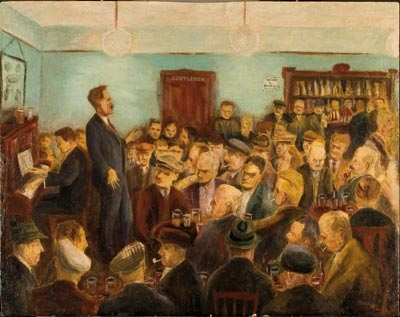

There were added expenses too – the garage where the jeeps for the excursion were maintained, the horses ending up on the banquet table, and the actors he called periodically from Delhi, even Bombay to entertain the soldiers. They staged raucous comedy shows, enacted explicitly belligerent war scenes from movies and sometimes condescended for the sake of the ladies and the children to do some love scenes. Of a soldier’s farewell to his beloved, two lovers uniting after a war, the news of a soldier’s death delivered to his lover. Much to my father’s distaste and to the consternation of the old soldiers, these were wildly popular with everyone, especially the younger officers. Father, however, did not protest much about it. The younger officers, junior ranked, would follow every piece of the action attentively, then cheer raucously at the final scene, waving their handkerchiefs and asking for an encore.

As for me, finding myself at a bit of a loose end after my exams, and having never seriously given much thought to a career, the hysterically amateurish theatre performances provided some kind of an outlet. And the manager of the troupe, who doubled as scriptwriter, director, was a gently encouraging man who having noticed the manner I diligently watched them at their rehearsals, one day invited me to act.

“My father will have my hide,” I laughed, putting him away, not once but again and again because he was very persuasive. But in small ways, I became involved. Standing behind the wings, script in hand, hissing out forgotten lines, in ensuring that the arrangements were perfect and as the owner’s son, my background proved helpful. But what I loved most was helping the actors change and with their make-up.

I had watched the bewildering transformation of plain, ordinary looking people into gorgeous, flitting creatures of the night, gay, carefree and full of laughter. The actors who helped each other with their make-up were only too glad of an extra-hand and I loved experimenting. Trying on different colours and shades, mixing and matching and my greatest compliment was when a chance remark came my way or I overheard the audience caught in the throes of admiration, “Wasn’t that great?Othello looked just the part.”

I remember how embarrassed the actor playing Juliet in one adaptation, had been when he had been given a note on a silver tray by a very correct waiter, from a senior ranking officer, pleading for an assignation. There had been great amusement, even a hint or two that with good makeup, he could easily humour the officer but the actor had put his foot down. He refused to play a female role again and later took me aside, and earnestly, making sure I did not misunderstand, asked me to please go easy on the make-up. “There should just be a hint that it is all fantasy. The trouble comes when everyone mistakes it for the real thing.”

I remember being intrigued by this bit of advice but by then I was much too infatuated. I was already playing some kind of honorary role, doubling up as resident director, casting agent, make-up person, even scriptwriter for the various troupes that came by. My father put up with it, because it was obviously popular and the guests who came in every summer and towards autumn, showed a marked enthusiasm for such performances but after a while, he decided that enough was enough.

“We can’t have this, you know. You cavorting around with these people. You are a businessman, not some kind of second-rate artist. I thought you saw it as a fun thing, something that would not let you get bored… but this, what you are up to, is nonsense,” said he.

He insisted then that I get involved in the business slowly,“You need to see how the hotel is run. Its like a business like no other, because each aspect is so very linked to the other.”

It was in his genes for father now felt passionately about the business, in a way different from grandfather’s. Grandfather, it seemed to me, had never let it become such an all-consuming passion, as it was now with my father. As was my love for the theatre, which I later realised was also some attempt on my part to assert my own against my father. When father talked of things like interlinkages and connectivity, in his dry, matter-of-fact voice, I could not but help but think of a theatre. Come on, it was much the same thing with the theatre. But my father, passionate and thus too blinkered, was too irritated to even countenance this thought.

I did try and get involved but the hotel, five decades old, now ran with clockwork precision. It had a life of its own, a routine and ways of being that it had imbibed in all this time. I had simply to stand aside, wonder and monitor. The menu after a while, made little sense, because the more dishes that were tried out, somehow ended up tasting little different from each other, or your taste buds after a whole simply gave up, fatigued with the idea of guessing and experimenting, When the master chef came up to me with his suggestions, I soon was ready with my excuses, pleading a bad throat, a poor digestion system, or failing eyesight which affronted him greatly because he believed greatly in using colour to enhance taste. Inside the hotel, where some years back, airconditioning had been installed, and the curtains were now kept perpetually drawn, I had the strange feeling of being a prisoner caught in a maze.

An unending sameness to everything. Every room was arranged the same way, even the walls had the same pictures bulk ordered from one of the country’s most eminent artists. My father said, the theatre had made me effeminate, too finicky. All hotels are this way. They give you the best comforts, but you can’t have it different, then people will try and impose their will on you, putting their preferences. You can’t have them thinking it is their home, it is only a home away from home, but temporary.

Anu Kumar’s latest book is The Dollmakers’ Island. (http://www.flipkart.com/dollmakers-island-anu-kumar-book-8190939130) More about her on Story Wallahs.