There is a telling anecdote about Kishori Amonkar’s early years as a classical sensation when she was rattling off the number of shows she had been booked for and her mother and guru Mogubai Kurdikar, herself a legendary disciple of Ustad Alladiya Khan’s Jaipur Atrauli gharana, heard her out and asked her if her calendar had enough days to spare for riyaz. Because if it did’t, she would not teach her anymore.

**

What young Kishori learnt from this gentle admonition was how fame and ‘saadhana’ were two different things and how a true artist cannot and should not ever mistake one for the other. This insight also made her fastidious about how she wanted to be projected as a musician and she grew increasingly detached from the ceremonies of stagecraft like bright lights, extroverted interaction with the audience, vibrant clothes and things that she considered to be frivolities in the way of ‘gaan tapasya.’

**

Though she would be critiqued at times for not appearing on time on stage, she would argue that for her, to “see” a raaga in the eye of the mind before she sang was important than to appear on time and not touch the core of the swara she wanted to scale. Her open displeasure towards fusion, popular genres of music and any kind of noise or distraction during concerts at times attracted a lot of ire even though male musicians of equal stature have been excused indulgently for far more erratic behaviour on stage and off it. But this discrimination could not have affected Kishoriji as much as memories from a time when her mother was humiliated at the concert circuit with shoddy living arrangements and paltry payments. These memories continued to haunt her and she in a way overcompensated for the lacks inflicted upon her mother by demanding with authority what was due to her.

**

She often said that she would not perform abroad because those who wished to hear her were welcome to come to India. She was also the pioneering force at early morning concerts that began at as early as 6 am because she was very particular about the timings that ragas were supposed to be sung in. She gave her first early morning concert in the early 80s at the Dadar Matunga Cultural Centre and established without saying a word that music did not have to adhere to the convenience of the audience. She was also averse to the way multiple genres were clubbed together at music events when classical music deserved space and silence to be heard and absorbed. Classical music, she believed, was not for those who only want entertainment. She disliked popular music also because according to her, here the musical notes were enslaved by words. In her own world, there was no place for empty vocal acrobatics or crowd pleasing jugalbandis. For her, the purpose of music was peace, not excitement.

**

And that was why she had issues with reality music shows that according to her were misleading young voices by trapping them in fame before they had even begun to develop an authentic understanding of music and even critiqued her contemporaries for appearing as judges on such shows. When she appeared in a populist format, it was only within a classical context. In 1964, she sang the title track for V Shantaram’s Geet Gaya Patthharon Ne. Twenty six years later, she composed and sang for Govind Nihalani’s Drishti but never considered dabbling with film music again because her mother told her that if she ever sang for films, she shouldn’t let her touch her two tanpuras. She did have a spiritual affinity with Meera bhajans and her album Mharo Pranam still flies off the shelves, years after its release.

**

The fact that she lived and sang on her own terms was at times not easily digestible to her critics but if she was affected by it, she didn’t show it because for her, music and the emotion quivering in a raaga were of primary importance. Everything and everyone else came second. Chasing approval in life or music was never her motive. Her life and her music blended intellectual depth and emotional immersion. She took no short cuts as an artist and had no patience for those who did. Like she said once in not so many words, “There cannot be Moksha without Sayyam.” And in her lifetime, she reached that point of spiritual sublimation again and again.

**

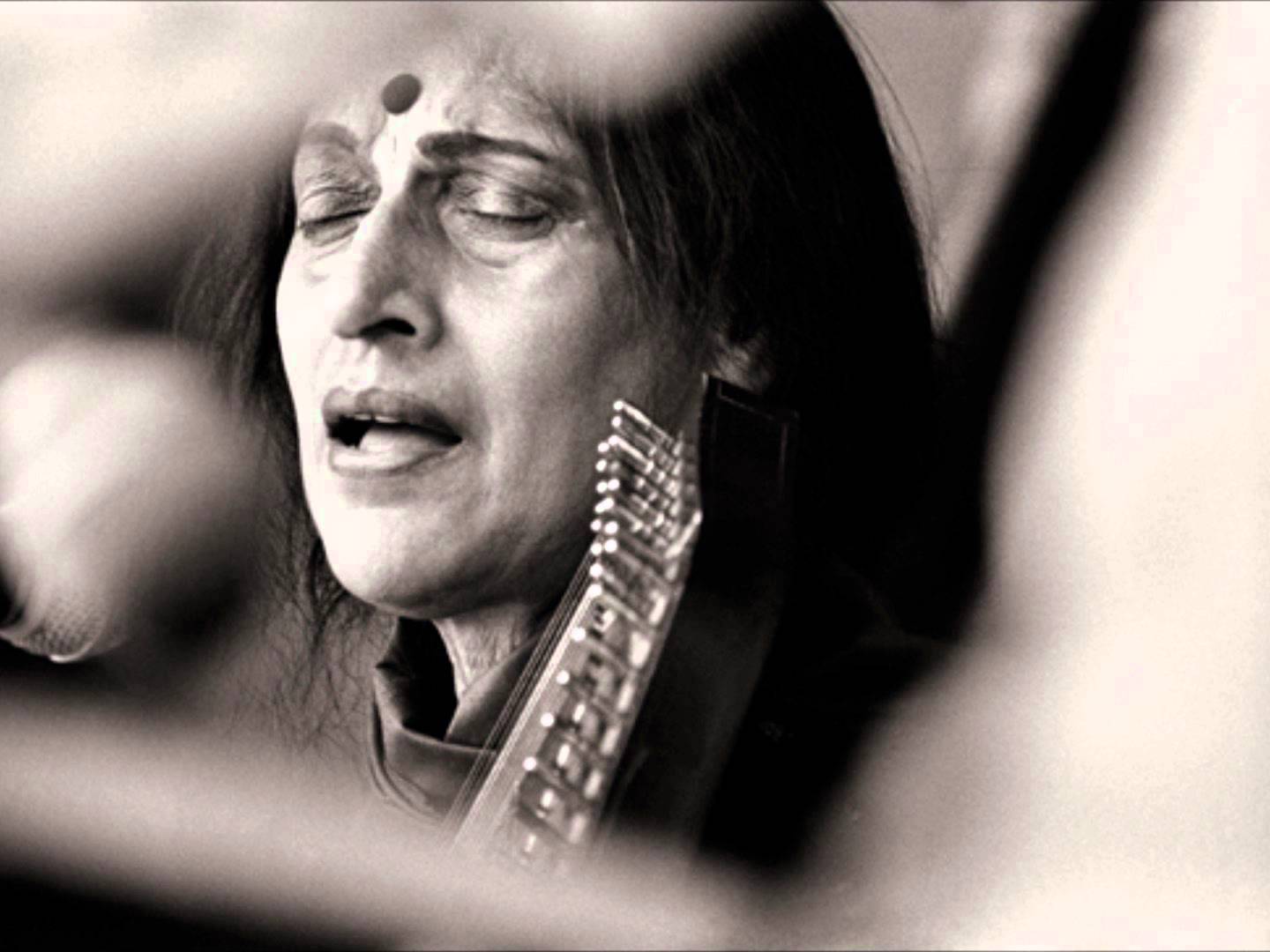

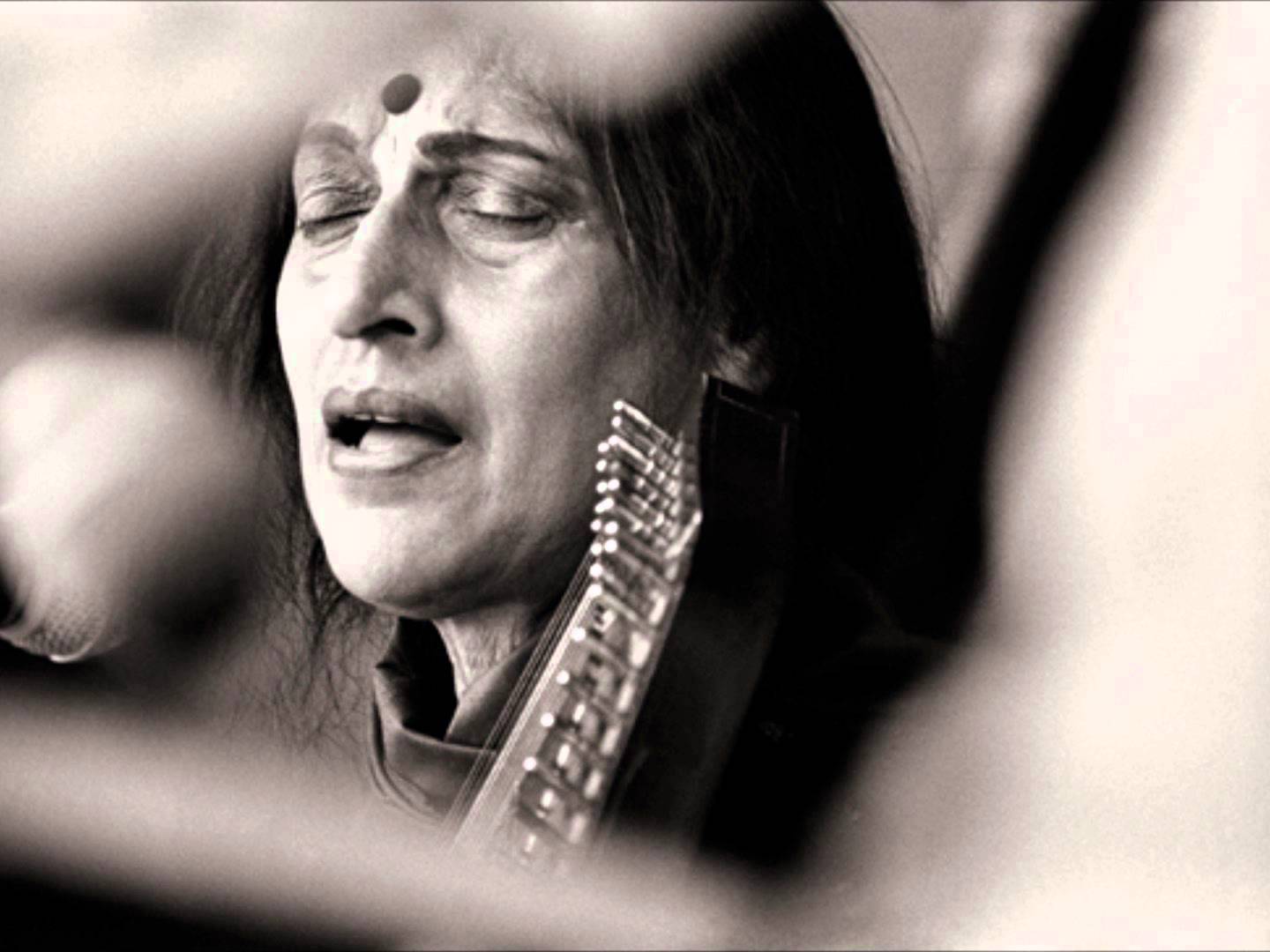

Those who were lucky enough to watch her on stage will remember her not for her mannerisms or her charisma but her introverted gaze, her piercing concentration as she searched for a note that would open the door to another one and then yet another one till she saw what she had set out to see. A raaga in its purest essence. Almost divine in its radiance.

Kishori Amonkar, the eternal seeker has found finally the final door to Moksha. But knowing her, maybe this is not the end. Maybe, this is just the beginning of yet another quest.

**

Reema Moudgil is the editor and co-founder of Unboxed Writers, the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, a translator who recently interpreted Dominican poet Josefina Baez’s book Comrade Bliss Ain’t Playing in Hindi, an RJ and an artist who has exhibited her work in India and the US and is now retailing some of her art at http://paintcollar.com/reema. She won an award for her writing/book from the Public Relations Council of India in association with Bangalore University, has written for a host of national and international magazines since 1994 on cinema, theatre, music, art, architecture and more. She hopes to travel more and to grow more dimensions as a person. And to be restful, and alive in equal measure.