As he, almost silently, glided into the living room, it was as if the curtains had lifted and the show had begun.

Cinemar manush (the man from the films) was how I would refer to him whenever I saw a picture of his anywhere, as a five-year-old. The man I had loved and loathed in Tapan Sinha’s cinematic adaptation of The Prisoner of Zenda (Jhinder Bandi). Ray’s actor. Charulata’s Amal. The original Bengali rock ‘n roll star. You would have known that had you seen him twist opposite Tanuja in Teen Bhubaner Pare. This and more flashed through my mind in that moment, as I stood up to greet Soumitra Chatterjee.

It probably took me that fraction of a moment to react as I stood a trifle transfixed. He took me in with that unmistakable glint still in his eyes, half-smiled, as if recognising exactly what scenes were fleeting through my mind and why it took me that fraction to react. He did his nomoshkar, requested me to take a seat, and took his.

It was the summer of 1994, I was in my late 20s and still in what I consider as my days of infancy in journalism. His clear, friendly voice and genial disposition had put me firmly at ease, and I took my notes furiously and assiduously. We talked cinema.

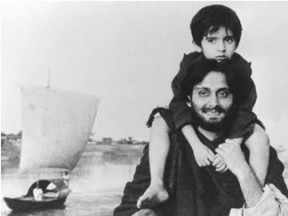

It was in 1959 that this lean young man, a debutant then, had trailblazed to instant fame in Satyajit Ray’s Apur Sansar. A noted French critic was to see the film more than 20 times and fly over to Calcutta to write a biography of the talented actor with the chiselled looks. During those 35 years of international acclaim, this same actor had never won a National Award. That sultry May afternoon at his modest South-Calcutta residence, Soumitra Chatterjee, the quietly eloquent thespian of the Bengali film industry, did not even insinuate this fact.

But he rued the crop of filmmakers whose “atrociously bad films” did not allow budding actors and actresses enough scope to develop themselves. Chatterjee saw the widening gap between good and bad films as something that had taken roots in the 70s itself when Bengali cinema stopped relying on literature for stories.

“Earlier, there was a middle path and even commercial films having a good storyline and some connection with the reality were around,” he pointed out to me. Chatterjee lashed out at filmmakers who, he contended, somehow managed to get a producer, made a cocktail from old and new films, and then just peddled the ware. There was no anger or disgust in his voice; if there was any, it was in what he said, “The actor has little to do in a setup like this. The only way out may be is to make films by oneself. But then, an actor’s business is to act.”

Chatterjee saw a dearth of actors of the stature of Uttam Kumar who often had a say in the script. So, did his (Uttam’s) death in 1980 sound the death-knell for Bengali cinema? Chatterjee did not agree, and argued that “since Indian films revolve around youngsters, Uttam Kumar would not have had the chance to shape Bengali cinema. At 55, he was shifting more to character roles. What we lost was a good character actor.” Chatterjee himself shifted to from being a “star’ to a character actor with feline grace. One never noticed the shift, because he always remained in the film circuit.

For all the disgust evinced by what he said than in the way he said it, Chatterjee remained optimistic, “Maybe one day there will be a crop of filmmakers who will understand the importance of the literary background and make good films.” More than 15 years later, I know why he did not predict the certain death for Bengali cinema – most of the Bengali films to have done well in recent times or won critical acclaim have embraced their literary roots.

His struck his own cinematic roots in 1959, but more by chance since the proscenium was his first love. “But I readily accepted when Satyajit Ray offered me the title role in Apur Sansar. I had seen Pather Panchali, Aparajito and Jalsaghar and greatly admired his work,” said he. After Pather Panchali, Ray had been looking for a young man for the second part – Aparajito – of the Apu trilogy. Some recommended Chatterjee but Ray found him too old for the role. Ray, nevertheless, made up his mind to make the third part after seeing him.

The film made waves and the rest was history – an association between Ray and Chatterjee began, which came to an abrupt end only with Ray’s demise in 1992. From Apur Sansar to Sakha Prosakha, Soumitra played Ray’s chief protagonist in 14 films, prompting Pauline Kael to call him, “Ray’s one-main-stock company.” He was also to have acted in the 15th – Uttoran, which was completed by Ray’s son, Sandip, after his death.

So what was it that made the duo surpass the only other such pair of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune? Soumitra attributed this to being nurtured in a shared milieu, where Tagore was an important factor, “Ray’s vision and mine cannot be compared. He was a great artiste and I loathe to bring about any comparison between him and me. Nonetheless, we looked at life with the same kind of attitude.”

He could not name just one favourite role. Apart from Ray, he had found it satisfying to work with Mrinal Sen (Akash Kusum and Mahaprithibi), Tapan Sinha (Atanka, Khudita Pashan), Raja Mitra (Ekti Jibon), Tarun Majumdar (Sansar Simante and Ganadevta), and Saroj Dey (Kony).

“Films like these were very encouraging since I was not only able to work hard, but apart from my duty of entertaining my audience, I could also put down some of my experiences, my aspirations and my attitudes towards life,” he said.

Remember, this was 1994. It was only in 2008 that Chatterjee was finally given a National Award, for Suman Ghosh’s Podokkhep. He had refused the award a few years back for his performance in Goutam Ghose’s Dekha. But now, Chatterjee, a much mellowed man accepted the award with a lot of grace. Had you been with me on that sultry May afternoon of 1994, you would have known it is a quality that he exudes like we breathe air. For it was only grace that ensured that a cub reporter like me did not feel dwarfed by his towering personality.

Subir Ghosh is a New Delhi-based independent journalist and writer. He has worked with the Press Trust of India (PTI) and The Telegraph, and handled publications/communications for the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), the Federation of Hotels and Restaurant Associations of India (FHRAI), and the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI). He specialises in Northeast affairs and is an advisory council member with the Centre for Northeast Studies (C-NES). He is the author of ‘Frontier Travails: Northeast – The Politics of a Mess’ published by Macmillan India, and has won two national awards in children’s fiction. His subjects of interest include conflict, ethnicities, wildlife, human rights, poverty, media, and cinema. He blogs at www.write2kill.in