There is a scene in Rahul Dholakia’s Raees where Vijay, the symbol of conscientious idealism in Salim Javed’s cinematic universe of the 70s, appears for a few seconds on a screen in an open air theatre to take a greedy capitalist to task for a coal mine that has caused poverty, death and persecution of poor miners. The film was Yash Chopra’s Kala Patthar but it could have been Deewar. Or Trishul where the protagonist was never deviant without a reason and where his empathy for others came from a back story of deprivation and loss. From a mortal injury to the soul.

**

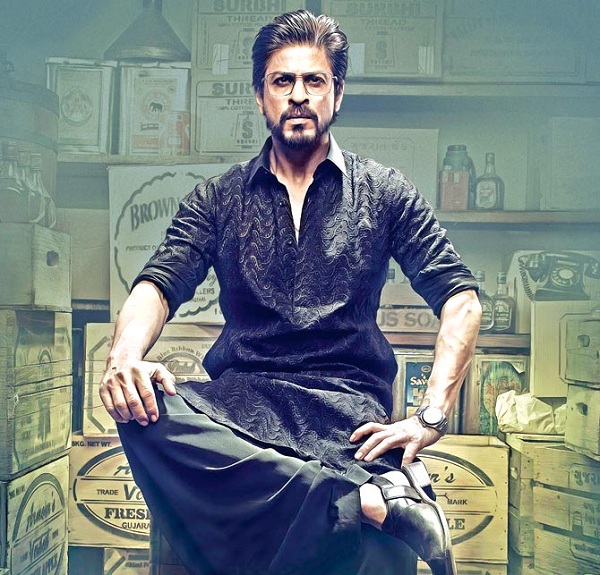

So this scene appears just when Shah Rukh Khan’s Raees is confronting a factory owner and asking him to pay compensation to his debt ridden workers. The moment does not totally work not just because it is a clumsy tribute to a simpler, more innocent heroism but also because Raees is primarily a bootlegger who at some point decides to be a saviour. The fire in his belly as a child is stoked by the desire to do “dhanda,” when he sneaks liquor bottles out of a heavily policed area in his school bag. There is nothing in his history that however explains the fracture in his morality. It is also hugely symbolic that Raees grows up in a Gujarat where Gandhi is now just a symbol, a mute statue whose spectacles are sometimes stolen to make a political point or in this case, filched by a child who cannot afford a pair.

**

The reason why Raees never chooses any other path is not clear though when he grows up and can afford it, he wants to create a utopia where every day will be Eid and every night Diwali and there will be an English medium school for every kid. But no, we don’t see why he becomes a bootlegger in the pursuit of this dream except that as a child he saw his mother being taunted by a policeman, and she retorted that no “dhanda” was too petty. She did clarify later that what you do should not harm anyone but what does that harm entail, is never specified. And so when Raees grows up, there is no fastidiousness when it comes to getting bloody and dirty for a few lakhs as in the scene where you see a brutal fight in the blood of slaughtered animals. And as he continues to grow more and more dangerous, you see him getting rid of his enemies with the same cold-bloodedness. In one scene he washes his blood spattered face before his wife who is expecting their child.

**

His character may or may not have roots in a real life story but there are clear references to Mani Ratnam’s Nayakan (refer to the bromance with Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub and the use of a waterway to hoodwink the police that is checking the highway for smuggled goods and the fierce loyalty he evokes in the people he helps). Still, he is primarily a profiteer who lacks the immediately relatable humanity of Iqbal in Manmohan Desai’s Coolie who also turned to politics to fight for equality or Sikander, another messiah played by AB in Prakash Mehra’s Muqaddar Ka Sikander who found solace in helping the dispossessed in a society that never accepted him as one of its own.

**

Raees shies away from addressing the primary question that every relatable protagonist must answer, “Who do I represent?” A question that Karan Johar’s My Name is Khan tried to answer but cleverly not in India but in the post 9/11 America. The closest the film comes to addressing the tragic politicised polarisation of communities is when Raees opens langars in four mohallas after a spate of riots and says, “When I did not discriminate between religions while doing business ..why would I do it now?” And in the singularly most memorable line he speaks in the entire film when he says, “Main dhanda karta hoon..par dharam ka dhanda nahin karta.” But in the end, even Raees who has kept religion and business apart becomes a pawn when in a crisis, he unwittingly gets embroiled in the smuggling of RDX.

**

This however could not have been an easy film to make because unlike Iqbal and Sikander, Raees is dealing with country where religion, politics and profiteering have become indistinguishable. So to make a film that does not offend anybody as it skims past issues like communalism and politics would have challenged Rahul Dholakia a great deal because he dealt with a lot of backlash for making a raw and aching film like Parzania, about the 2002 riots where along with many others, a young Parsi boy went missing, never to be found. How much sanitisation went into the way the film was colour coded is visible in the scene where a rath carrying a leader advocating a liquor free Gujarat enters Raees’ colony but his supporters wear pink stoles and their flags are not referencing any recognisable political party.

**

In one of the few really poignant scenes in the film, Raees asks Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s Superintendent of Police Jaideep Ambalal Majmudar, if he can live with his blood on his conscience? In the end, that is the most important question the film asks. In a country where divisive politicians walk free after causing unspeakable crimes, is the law really serving the players or the pawns?

**

The performances are uniformly strong but it is Nawazuddin Siddiqui who nuances an underwritten part with a still, steady, all seeing gaze and a cool minimalist body language and confidence that commands every scene he walks into. Zeeshan Ayyub could have been given more to do considering what a powerful actor he is and he surely deserves by now a stand out part to shine in without having to play second fiddle to anyone. Shah Rukh Khan plays the part with obvious enjoyment and one of his best scenes is when he is being humiliated by a former mentor just when he is starting out. It is one of the few moments where you see vulnerability in the aura of a superstardom that has now become a part of his persona. That scene and the last one where he confronts his mortality with a humility his Raees has not shown through out the film.

**

Mahira Khan neatly fits into the Hindi film industry’s definition of the pristine “gharwali” whose eve teasers must be taken to task in a world where a Sunny Leone is thrown around like a piece of meat amongst a pack of animals in the villain’s den and nobody feels repelled. And you wistfully recall Zeenat Aman in Qurbani singing Laila O Laila across a dance floor that no one dared defile. Where she took off her faux fur stole only when the man she loved walked into the club. You remember a time when a heroine could be a club dancer and sensuous and still be inviolable. Mahira is a beauty though and too bad we won’t see any more of her if the current political climate persists. The music is weak and K.U. Mohanan’s camera captures Gujarat like a box of rainbow candies. This is not a bad film. It is even brave for daring to give us the first unapologetically Muslim protagonist in India since Manmohan Desai’s Coolie if you discount Chak De India but it lacks a coherent sense of purpose and instead gives us a hero who stylishly plays to the gallery but lacks the depth and the existential hurt to make us root for him and to cry with him and for him.

**

Reema Moudgil is the editor and co-founder of Unboxed Writers, the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, a translator who recently interpreted Dominican poet Josefina Baez’s book Comrade Bliss Ain’t Playing in Hindi, an RJ and an artist who has exhibited her work in India and the US and is now retailing some of her art at http://paintcollar.com/reema. She won an award for her writing/book from the Public Relations Council of India in association with Bangalore University, has written for a host of national and international magazines since 1994 on cinema, theatre, music, art, architecture and more. She hopes to travel more and to grow more dimensions as a person. And to be restful, and alive in equal measure.