This Saturday morning, I walked into a multiplex to watch Tigmanshu Dhulia’s Paan Singh Tomar to find exactly 10 people in the hall. It did not matter. The emptiness around me filled up the moment Brijendra Kalay’s brilliantly shifty, stuttering scribe came face to face with the erstwhile national steeple chase champion, army Subedar and current baaghi, or rebel (not dacait..because, “dacait sirf parliament mein hote hain) Paan Singh Tomar. From that moment on, the audience, regardless of its number was taken out of familiar contexts, both cinematic and of modern urban living and taken into the unfamiliar contours of a story that may be playing out even today in Chambal or in a forest where a farmer denuded of his farm land now lives as a hunted rebel and having been denied the privilege of being protected by the law, now refuses to live by it.

Remember the NSG commandos who post 26/11 were herded into BEST buses after having saved the face of nation and innumerable lives? The faceless, nameless soldiers who die in sub zero climes or in avalanches or of bullets and blasts and land mines because we expect them to? The ignored Kabbadi and hockey players, the hungry, underfed athletes who like Tomar says in the film, are expected to bring back medals fuelled by apathy, a few bananas and eggs? Who never get the sponsors, the media attention and the adulation that cricketers get? Or the farmers who now are being chased, bullied or cheated out of their livelihood, their land because we need more cars, more malls, the ministers need more earth to unlawfully mine? Paan Singh Tomar is the story of that farmer, that soldier, that athlete who is expected to and does put his land, his country and the national honour first and in the end discovers that it was all for nothing. There is a poignant scene in the film where Tomar sits before an emblematic policeman who no longer cares which side of the law he is on. He spreads out the medals, the newspaper cuttings of his achievements as a seven time national champion to prove that he is someone who gave everything he had to his country. Now he wants help. To protect his small piece of land and his son who has been beaten to a pulp by his trigger happy cousins.

The policeman plays with the medal. Looks at the cuttings with amused disinterest and says, “Saboot kya hai ki yeh tum ho?” (What is the proof that this is you?)

He continues, “Steeple Chase? Kaun kisko chase karta hai?) (Steeple Chase? So who chases whom?)

The futile conversation ends with the ex army man furious with the realisation that all his medals, his years in the uniform, running through barriers, man made and real mean nothing because now he is just a defenceless farmer. The cop throws his medal and all the years of his life at his face and then begins a spiral that replaces the man who did not fire even a single bullet as a soldier because the army considered him too precious an athlete to be sent to war, with an outlaw who must kill to defend his loved ones, his honour. And to be heard. You cannot miss the sub text when Tomar, now a feared bandit in Chambal’s dusty, blood thirsty wastelands is busy plotting day to day survival, kidnappings and murder and a transistor in the background is exulting over the news of India’s gold medal in hockey.

When he hears himself being referred to on news as a sportsman who now brazenly fools the law and loots and kills, he can’t help but notice the irony. A seven time national champion never made it to the news. But a bandit did.

The story of Tomar could have, should have ended happily. Here was this ravenously hungry, effortless runner, sweating joy from every pore and handpicked by his regiment as a talent to watch out for. He is told that he can eat as much as he can, if he becomes an athlete and is asked to run with a box of ice cream and deliver it to an officer’s home before it melts, just to prove that he is good enough. He manages it and is happy to pounce on a bunch of bananas after his first win. The real meaning of victory and loss will capture his soul much later. He meets nepotism early as when he is made to leave his favourite event, the 5000 metres and is asked to run the Steeple Chase instead. But he begins to run through this new challenge and then never stops.

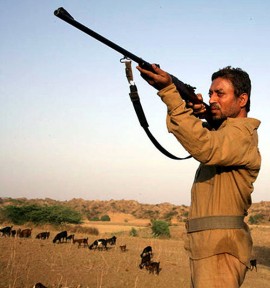

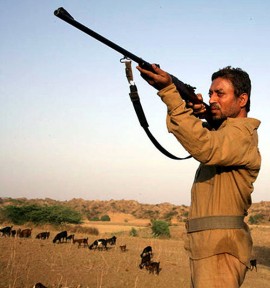

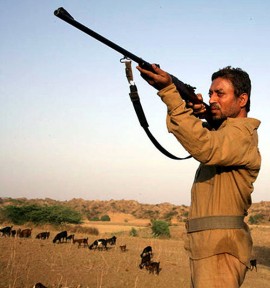

And now we must mention Irrfan Khan. This is not a performance for the camera. It is not even for us. Or for the audience who will watch him in this film a few decades from now with disbelieving awe much like we watch Balraj Sahni in Do Bheegha Zamin today and wonder what this actor was made of. Irrfan’s craft or his Tomar is not about shirt ripping, visible muscle. The muscle is much deeper. Somewhere lodged in the soul. His Tomar is not the vanity of strut and swagger and the reliance on tried and tested mass triggers. This is not a cliched anti hero. He is nothing like the dacoits we have seen in Mujhe Jeeno Do, Dacait and counting. Yes, he could have been at home in Shekhar Kapoor’s Bandit Queen but only because director Tigmanshu Dhulia was part of the crew that fashioned that seminal film about dehumanisation and a redemption that never ends anywhere but on the banks of a river of blood.

But coming back to Irrfan. And the fact that he has made way for the soul of Tomar to inhabit his limbs, his eyes, his voice, his love for everything that he as a human being must have held dear before it was all taken away. There he is, a 20 something upstart, floating above puddles and barriers, his lean perfectly coordinated limbs of a runner oozing the pride of a winner. The naive Indian in an international meet who cannot run without his cheap, canvas shoes. The furtively passionate husband who sends his children for a lemon juice treat when he wants some time alone with his wife (Mahie Gill, authentic to the core). The patriarch who has spent too many years away from the bloody hinterlands of Madhya Pradesh to really understand the politics of violence and corruption. The rebel in sweaty khakis, walking with his men into the deceiving heart of Chambal with the same discipline that he brought to his years on the steeple chase track. He does not like corpulent men, be they police men or journalists or his comrades though he loves mutton, cones of softy and ice-cream with gulab jamuns.

He trains his men like an army commander or a coach preparing his boys for a medal. He becomes a bandit but the champion runner does not leave his blood stream. Life is still a steeple chase race for him and he won’t stop running till the race, for the better or for worse is over. Everything is about reaching the finishing line. That feeling of closure when you know you did everything you could.

That feeling comes to him amid a hail of bullets when he hears applause and not just gun shots, his finger signalling to his mind, the last burst for life, for vindication, for victory that may never come. You see him slumping and you know you have lived a life time with this character, with this actor who is true to what he does, down to his marrow. Without any exaggeration, in an industry packed with bloated egos, self-serving cliques and manipulated glory, this is the performance of the decade. And if this film does not show us that this actor is amongst the best we have ever had, we don’t deserve him.

The beauty of this performance is that it is not about Irrfan Khan. Just as Maqbool was’nt. Just as The Namesake wasn’t. Or even Makdoom Mohiuddin wasn’t (the poet he played in the TV series Kehkashan). It is about Paan Singh Tomar. Irrfan’s biggest achievement is that we will never forget Tomar. If we atleast make the effort to watch this film.

Tigmanshu Dhulia’s canvas is bursting at the seams with broad, fine, and sometimes almost invisible to the eye nuances. This is one of the films you do not want to review but relive because just one viewing is not enough to imbibe the written word, the visual expanse, the details of small town bazaars, the posters stuck on walls, the songs being played on loud speakers, the mujra in the fields, the nexus between the police and the outlaws, the barracks where the real Paan Singh Tomar spent some years, villages where half of India still lives even though we do not see them in our films or in our advertising unless in the context of politics or land scams and violence. Art director Heerendra Dwivedi’s sense of visual authenticity and Aseem Mishra’s cinematography are note perfect.

It is also is hard to understand the criticism that the film has no emotional heft compared to, say a Bandit Queen. This film is not about rape, about the politics of gender violence but about the loss of innocence, of faith in a nation we all believe in till we are left alone in a State sponsored riot or a scene of crime with the police man looking the other way. The criticism that we don’t see the progression of a soldier to a bandit in the soul of Tomar, does not cut ice either. When the man who chased nothing but the joy of brushing against the finishing tape chases the enemy who took away his life of peace, domesticity and the identity of a national treasure, he shouts out the desperate question, “You took away the running tracks and forced me into the terrains of Chambal…how can I ever get back what I have lost?” This is a film that has been made as a tribute to the Indian we have forgotten. And when most of the 10 people in the hall left before Dhulia’s parting tribute to athletes (some forced to sell their medals, others dying in penury) could come to an end, you wonder if all the effort that has been put into this film is worth it. For now, let us just be grateful that the film was made and though finished in 2010, saw a commercial release in 2012. Thank you Mr Dhulia. Thank you Irrfan Khan for reminding us just how ungrateful we are as a nation.

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight (http://www.flipkart.com/perfect-eight-9380032870/p/itmdf87fpkhszfkb?pid=9789380032870&_l=A0vO9n9FWsBsMJKAKw47rw–&_r=dyRavyz2qKxOF7YucnhfXw–&ref=4fe1efd1-de20-4a30-8eb8-ef81a99cb01f )