In the middle of the spectacularly lopsided India-England test series, I was trying to steer a simulated Ashish Nehra on this rather dated computer game. It was tough – the left-armer was running in and from around the wicket, moving it away from the left-handed opener. At a friendly 125 kmph. The batsman (Taufeeq Umar, walloping away) shuffled and after having the swing covered, smothered it down mid-off. Or cockily muscled it over long-off. Ball after benign, slow-drifting ball. The batsman sported a stony calm – it was easy to tell from his mien – and the ease he was flailing this effete attack with reflected what the game’s developers thought of Indian pacemen in the alternative, non-CG (Computer Graphics) universe. Sometimes potent, largely beneficent. Never breakneck lethal.

Through the four tests in the series, James Anderson, Stuart Broad and Tim Bresnan led the English attack with pace and bounce that eluded the Indian pacers, barring Ishant Sharma in a short burst at Lord’s. That Praveen Kumar, who chipped away with his gentle leg-cutters, is India’s highest wicket-taker (15) of the series is a damning sum-up of an attack also agonisingly short on its traditional strength, spin. Kumar is a picture of old-fashioned test match doggedness but he’s not a frontman pacer M S Dhoni would string up a packed slip cordon for. With injury taking Zaheer Khan out of action and the other Indian pacers seldom clocking it above the low 130s (Ravi Bopara, England’s part-timer, matched them for pace at The Oval), the series always looked on course for the whitewash it ultimately was.

MS Dhoni, and the fan, have reasons to slam the batters who failed to build totals around the brilliant, indefatigable Rahul Dravid. The big chink, however, has been the absence of a pacer who could fire it in. The bosses back home are likely to tape the crack and look at a home series for the pacers to return to form. That’s how it has been. Quick was never key to the scheme in India, where pace is not a dominant culture; where boys from the gully always fancy being in the “batting team” and spinners stack up the pantheon of bowling greats.

The legend of Kapil Dev had a nice ring also because it had the unlikely tale of an Indian pace bowler becoming the highest wicket-taker in test cricket history. The nation’s highs on the cricket field – from the 1983 World Cup title to the now-relinquished No. 1 test side status – have often been rung in by its revered spinners, bowling all-rounders and more consistently, batting stalwarts. But in a rapidly changing game, India’s resurgence in the test format would largely depend on a new generation of pace bowlers who could complement an impressive bench of batsmen waiting to enter the big league.

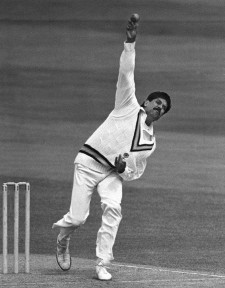

No pacer, apart from left-armer Karsan Ghavri (109 wickets from 39 tests at an average of 33.54), had consistent returns when Kapil was mining pace and swing off the sub-continent’s dustbowls in the late 1970s. Roger Binny, who led the seam attack with Kapil in the 1980s, has 47 wickets from his 27 tests at 32.63. Madan Lal, another frontliner from the Kapil era, used to skid it in and make the cut as a pacer. He ended up with a career average of 40.08. Chetan Sharma and Manoj Prabhakar provided the cheer in bursts but it was Javagal Srinath, the gangly pacer from Karnataka, who staked serious claim to Kapil’s mantle as a formidable new-ball bowler. By the end of his career, he was widely considered the fastest bowler India ever produced. He’s also one of the three Indian pacers, along with Kapil and Zaheer Khan, who have scalped 200 wickets in test cricket.

The statistic is revelatory. England, in the post-Kapil era alone, has produced five quick bowlers – Darren Gough, Andrew Flintoff, Matthew Hoggard, Steve Harmison and James Anderson – who have gone past the 200-mark. Post-2007, England has produced six quality pace bowlers in Chris Tremlett, Stuart Broad, Tim Bresnan, Graham Onions, Steven Finn and Ajmal Shahzad; all in contention for a place in the test squad that already has Anderson as the pace frontman. India, during this phase, had four quick bowlers making their test debut with only Ishant Sharma (123 wickets from 38 tests at 34.54) looking the part. England has Liam Plunkett, Chris Woakes and Jade Dernbach on the next rung, while India – the buzz on Varun Aaron’s ‘fastest ball’ and the promise the likes of Abhimanyu Mithun, Pankaj Singh and Jaidev Unadkat hold apart – could do with some cheer. Especially with Khan touching 33 in October.

In the 17 years after Kapil’s retirement, India has produced only three fast bowlers who have crossed the 100-wicket mark. While Khan and Sharma are regulars in the present outfit, the third – Irfan Pathan – is out of contention. During this period, South Africa had Shaun Pollock, Makhaya Ntini, Dale Steyn, Morne Morkel, Andre Nel and Jacques Kallis; Brett Lee, Jason Gillespie and Mitchell Johnson debuted for Australia and Pakistan, that high-yield breeding ground for pacemen, released Shoaib Akhtar, Mohammed Asif, Abdul Razzaq, Umar Gul and Mohammed Aamir.

It was not express pace that won India the test series in England in 2007. The three frontline pacers on the tour – Zaheer Khan (18 wickets), R P Singh (12) and S Sreesanth (nine) – accounted for 39 wickets in the series, none of them with claims to fiery pace. But then, there was the redoubtable Anil Kumble (14 wickets in the series) to turn to. For a team defending its world-beater title with its best seamer out injured and best spinner struggling for form, against a team boasting of at least five premium-quality test batsmen, India needed more than gentle away seamers and mid-pitch chatter.

Through decades, reasons have been circulated demystifying the absence of a “pace culture” in India; the more prominent ones being the inability to create and nurture natural athletes with the pacer’s build, the absence of a strong cricketing tradition or a streamlined, top-quality coaching mechanism in the north-western regions (an argument pegged to the rich turnout of pacers neighbouring Pakistan has managed), the preference of rubber balls in street cricket over the taped balls used in Pakistan and the traditional thinking that favours pace through the air to overcome the lack of bounce in the sub-continental pitches.

The rise of Zaheer Khan – who relies more on movement than pace – as India’s premier strike bowler and the theory of Munaf Patel being ‘conditioned’ to steadily lose his pace tell the story of a conservative Indian view on pace. The reputation of having been effective in favourable conditions, even in their overseas tours, is unlikely to carry the Indian pacers far as they head Down Under later this year. For a side that has its highest wicket-taker trying to save his place on his batting steam, India is in serious need of a young, frontline pacer as the team enters an era of rebuilt, rejuvenated test match sides. He’s not going to pop out of four-over spells in flashy T20 leagues. Till he turns up, I’ll try adding pace to Nehra on my monitor. The need, really, is for speed.

Krishna Kumar is a freelance journalist/writer. He lives near London, has a son and four half-drafted screenplays. Earlier, he was with The New Indian Express, Deccan Herald and The Times of India covering hockey leagues and civil aviation plus some stuff that falls in between.