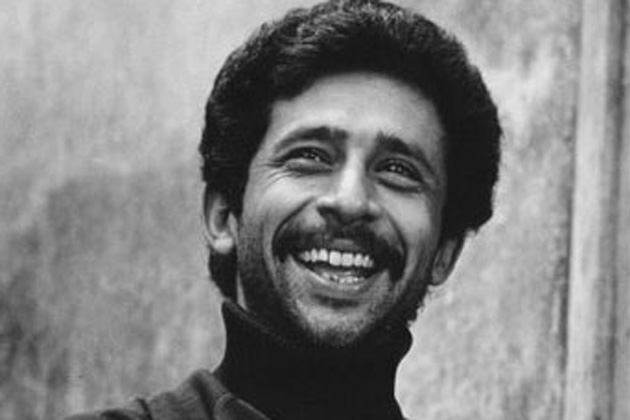

“Javed bhai, hum Dilli haar gaye hain!” (We have lost Delhi), yells Naseeruddin Shah as a violently bitter sepoy in Shyam Benegal’s Junoon (1978). That scene is hard to forget. As is the fact that it was on the sets of Junoon that Shah first met Ismat Chughtai, one of the bravest literary and feminist voices in India.

She was playing a small cameo in the film and years later Shah’s theater group Motley would stage a few of her stories.

Ismat Aapa Ke Naam, was back in town and Shah and wife Ratna Pathak were having breakfast on the lawns of a city hotel. The conversation veered towards Chughtai whose stories Motley has been performing for over a decade. Shah inhabits many characters in Gharwali, the story he narrates.

He plays the onlookers lusting over a woman in a bazaar, the woman herself who knows the power of her sexuality and how to make her way in the life of a lonely, middle-aged man. Without a single prop, he even becomes Chughtai who is invisible in the story and yet present in every delicious cadence.

So does Chughtai take over the stage or is it his imagination that brings her characters to life?

He says, “I don’t want to make acting sound mystical because it isn’t but I swear, there are moments when I feel her guiding me with invisible strings. But again this kind of inspiration does not strike an unprepared actor and we prepared ourselves for six to eight months, just reading the text. I feel very close to Ismat Aapa, I have this connection with her and I can feel her beaming at us from above whenever we perform.”

He continues, “I am astounded by the richness of her stories..that even after reciting them for over a 1,000 times, a gem of a line suddenly reveals itself. She had great generosity and wrote about human frailty with compassion, even if her subject was a drunken man beating his wife. And her relevance even today cannot be questioned because be it class consciousness, gender issues, the equation between a man and a woman, she had uncanny prescience. That is what great writing is all about. It is endlessly surprising and meaningful, be it Waiting for Godot that we have been performing for over 30 years or Dear Liar that we have performed for 20 odd years .”

Reviving Ismat and Manto was Motley’s way of paying a tribute to India’s often neglected literary legacy in cinema and even in our education system. But Shah has worked in Pakistani films like Khuda Kay Liye and Zinda Bhaag and even the Indian audience is discovering the wealth of Pakistani writing via television serials.

So has Pakistan looked after its literary wealth better than us?

He says, “Yes, I would say so but then their legacy is smaller and more compact. Ours is scattered and vast. There are many more literature based occasions in Pakistan than here. They have brilliant writers, humorists, satirists and women who began writing much before Ismat Aapa who we know nothing about.”

He nods in agreement when Ratna interjects, “I don’t think the average Pakistani is connected to his literary legacy any more than his Indian counterpart…but the producers of content in Pakistan have more to say and they respect writers a lot more then we do in India.”

He adds, “Do you know that Doordarshan did not give Gulzar bhai any money to make a new series on poet Nazeer Akbarabadi after he finished Mirza Ghalib (with Shah in the lead)? It was because the TRPs were too low for Mirza Ghalib while everyone watched Hum Log and Buniyaad. Today, everyone I meet, talks about Ghalib so the series triumphed in retrospect. But who has the attention span to read Ghalib today? That is why we have a Yo Yo Honey Singh.”

Balancing work and parenting…

Shah had once mentioned how his relationship with his father was based on naumeedi (disappointment) and how he was never enough for his father. Has he been a better parent? He laughs, “I don’t know how successful I have been. There is something to be said for memetics as well as genetics. I fear, despite acute consciousness of how not to parent, I have in some ways, found myself aping my father while dealing with my children. There was no closure in my relationship with my father while he was alive but now I find myself understanding him and in a way, things have come full circle. I now know what it is like to walk in his shoes.”

Speaking of full circles, he staged Shakespeare in his first ever performance and then did Vishal Bhardwaj’s Maqbool, (based on Macbeth), auditioned for Attenborough’s Gandhi and finally got to play him on stage and in Kamal Hassan’s Hey Ram, studied in St Joseph’s College in Nainital and went back to shoot Masoom there..

How many times has life come full circle for him?

He laughs, “Always! In most things. I love watching tennis and cricket and whenever there is an unfair umpiring decision, a batsman who stays on despite being out, a bad line call, or a player suffering for no fault of his, I always see that inevitably, nature finds a way to compensate and the odds are evened out. So yes, I have been compensated enough.”

He once remarked that the job of an actor is to never play himself.

Has he ever played himself in a role?

He says, “I have been present in all the characters I have played. Be it the slum dweller with a venereal disease (1981’s Chakra), a man who has been given `30 crore to spend in 30 days (1988’s Maalamaal), an angry villager (1984’s Paar), a young zamindar (1975’s Nishant)…through each character I have discovered and unmasked facets of myself..”

He adds, “I have never been satisfied and when you are not happy in your skin, you find comfort and release in becoming other characters. That has worked for me. I am glad I did not become a film star and did not have to play myself in film after film just because the audience expected me to. I love theatre, working with young actors, conducting acting classes, spending time with my kids. None of this would have been possible if I had become a star.”

Is great talent a gift and a curse..given the number of suicides committed by actors?

He shakes his head, “I don’t subscribe to that theory. I mean, what did Philip Seymour Hoffman and Robin Williams have to be depressed about? But again, that is like asking, what business someone had getting a bout of jaundice..

It is not that actors don’t have demons but in Hollywood, there is a tendency to nurture them. I felt a tremendous sense of personal loss when Hoffman and Williams passed because they had so much to give. I cannot imagine what it takes to hang yourself by your belt. Hollywood like I said, in a way celebrates such things.

I remember during the shoot of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, I was put up in a fancy hotel and the woman behind the reception desk asked me, “Do you want to see the room where John Belushi (comedian, actor, and musician) killed himself? You will be charged extra for that!”

How does he look back at his film choices..

He smiles, “Life is about coping with whatever is thrown at you and I have just done that and clawed my way up when I had no other option. I have managed to stay afloat.”

Has money been important?

He says, “Yes, but it has never been the only reason behind my decision to choose a role though out of the 250 odd films, I have done..at least 100 are embarrassingly abysmal. The only redeeming thing about them being that they came and went without being noticed! Films like Mujhe Meri Biwi Se Bachao, Zinda Jala Doonga and Jackpot!”

Surviving and thriving…

He ponders, “I did not relish eating from poky little dhabas and commuting during rush hours in local trains and thank god, I have not had to in the last 30 years. I have had enough to keep body and soul together and I have also had my parents’ example to guide me. My father earned `1,000 out of which `600 would go towards school fee and they would subsist on `400 and manage to save too! My father never bought anything new and my mother would darn old clothes and we never asked for anything because we knew we wouldn’t get it. That affected me deeply and am grateful for what I have and have no unfulfilled desires.”

Will there be a book on his life?

He nods, “My book of memoirs will be released next month and when I look back, I can see myself on stage for the first time, looking at the pitch-dark auditorium from the perspective of a performer and feeling the most intense fear I had ever experienced. But it lasted only till the moment I spoke and the audience reacted. And then I was home. I belonged there and I have never felt nervous again because acting is a joy and I would rather die than not act. I have never been afraid I guess because the fear comes when you worry about how you will be assessed. I have never had that worry. My acting hero was and is Geoffrey Kendal and I have admired Indian actors but only till they became larger-than-life.”

Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, Bangalore, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, an artist, a former RJ and a mother. She dreams of a cottage of her own that opens to a garden and where she can write more books, paint, listen to music and just be.

with

with