How empowering that the final scene of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women (Now showing on Amazon Prime) does not end under a rain drenched umbrella with a romantic proposal but a close up of Jo March’s ( a perfectly cast Saoirse Ronan ) face as she watches her book being printed and brought to life for future generations of little women. The moment perfectly sums up what Jo says earlier. That women are not just their beauty but their mind and soul and ambition and will. If only the makers of “She” , now trending on Netflix or so many others who pretend to tell ‘her’ stories understood that. Maybe then they would stop reducing women to pawns being moved from one square to another.

Compare Imtiaz Ali’s production ‘She’ with Gerwig’s women. ‘She’ is supposed to represent some hidden feminine dimension but it is a study of a woman’s debasement and powerlessness even though she wears a police uniform. She is repeatedly humiliated by her husband, is pushed around by her seniors and laughed at by her colleagues. She is then chosen to go undercover because she has “something special.” But that special quality is reduced to her physical statistics by a senior officer who uses her as a bait to trap criminals. We see her long legs again and again pacing the nightscape. She shows no sign of a will or volition and once when she does, her senior casually calls her a”bitch.” It is also suggested to us that she can come into her own power only when she uses her body as a weapon .

She says nothing meaningful through the series and when she does, it is not about the bigger questions about her life. But about how men don’t look at her when she is with her prettier sister. Because, really, that is the only thing women want in life. An approving male gaze. Even if it is lustful and violating.

Walking into Gerwig’s universe after watching ‘She’ is cleansing and uplifting. Because the women in it are not male constructs. They are complex, sublime and real. In Gerwig’s magical hands, Louisa M Alcott’s classic book becomes what it was intended to be. A story of women who want to make their way in a world that as Laurie (Timothée Chalamet) says once, has clubs of male eminence with restricted membership. Because men don’t want competition from women in matters of greatness.

Greta knows this all too well, having been denied not just awards but even a nomination for direction repeatedly by award juries made up largely of men.

She also takes the time to point out how women telling the stories of women are trivialised . And how they themselves buy into the illusion that their stories don’t matter. But as Amy (a magnificent Florence Pugh), tells Jo astutely, a story becomes important only when it is told.

In a world where a woman’s docility is prized and wilfulness undermined, we see Jo surrounded thankfully by people who do not want to erase her temper, her force of character.

As when Jo’s mother tells her that a spirit like hers is too “lofty” to be tamed.

The search for authenticity drives the women in the film.

And so an academician (Louis Garrel) unwittingly becomes Jo’s soul mate when he critiques her writing for its unconvincing masculine themes. He asks her a question, every woman aches to be asked, “Do you have someone you can discuss your work with?”

In another scene, Meg (Emma Watson )flaunting a borrowed name and dress at a ball is called out for inauthenticity by Laurie who says to her, “what will Jo think?” This is not him censoring her for a choice she has made. It is a reminder that that she is not what she is pretending to be.

Gerwig’s universe treats all women kindly. Even the formidable Aunt March ( Meryl Streep) who has her own take on domesticity, freedom and responsibility.

The real surprise in the film is Amy with her firm, powerful voice, her spine. Whether she is reminding Laurie of the privilege of being a rich man with endless choices when he is judging her for marrying for convenience or telling him that she won’t accept him if she is his second choice, she has depth that has not been usually accorded to her. Not even in better versions like Amol Palekar’s Kacchi Dhoop which was aired on DD in 1987.

Gerwig’s film even recognises the politics of race and in a remarkable scene, Marmie March (Laura Dern )acknowledges the “shame” of being an American in a country that needed a civil war to abolish slavery.

In the end, everything that happens to the March sisters is finally fodder for a book Jo was born to write. In a nod to JK Rowling’s life whose work was rejected by over a dozen publishers, Jo’s manuscript too is read by the daughters of a publisher who request him for more chapters, clearing the way finally for its publication.

As Jo negotiates for more money and the integrity and copyright of her book, she possibly channels what Alcott experienced then and so many women writers/artists go through even today.

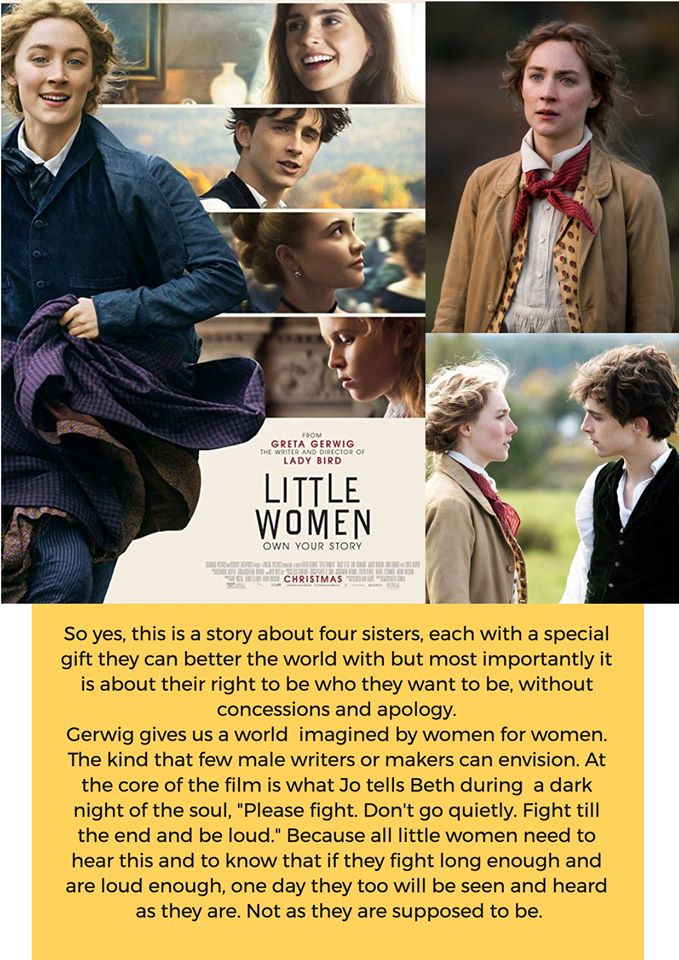

So yes, this is a story about four sisters, each with a special gift they can better the world with but most importantly it is about their right to be who they want to be, without concessions and apology.

Gerwig gives us a world imagined by women for women. The kind that few male writers or makers can envision. At the core of the film is what Jo tells Beth (Eliza Scanlen ) on a dark night of the soul, “Please fight. Don’t go quietly. Fight till the end and be loud.” Because all little women need to hear this and to know that if they fight long enough and are loud enough, one day they too will be seen and heard as they are. Not as they are supposed to be.