It was a sunny winter afternoon, and as cold as it gets in West Bengal. We, a group of journalists, were on a press trip to Mahishadal in West Bengal’s Midnapore district. It was one of those occasions when seniors would be tied up, giving a rookie an opportunity to report. With barely a year in the profession with news agency Press Trust of India (PTI), and that too on the desk, I needed this break. Chief Minister Jyoti Basu was to address this rally. With kar sewaks at their dance of death in Ayodhya, Basu would surely have something to say. My news item would be carried. All through the bus journey from Calcutta, I had been animated. Happy. It was December 6, 1992.

The rally started and one after another speakers blared Leftist rhetoric and jargon. All decrying the kar sewaks who were camping in the North Indian temple town. Unsparing in their trenchant criticism of the PV Narasimha Rao government which had allowed the assemble of thousands of Hindu rightwingers waiting to go on the rampage. The crowd here, not that big since this was a traditional Congress stronghold, stayed in rapt attention. We journalists remained by the sidelines, bored with and occasionally exchanging knowing looks at the Leftist words of wisdom, letting the fiery words enter through one ear and leave through the other. Waiting for Basu, we were.

Soon he was there and was barely into his inimical, staccato speech when someone stepped up to him and whispered something into his ear. We had an uncanny feeling what it might have been. Basu apologised to the crowd and nonchalantly left. When the drone of the chopper drifted into our ears from not afar, we were ready to pack up. An important comrade came up and huddled us back into the bus parked a good half kilometre away. “It’s happened. But please keep it to yourself now. We have a restive crowd here.” Grimly we returned. No one spoke during the two-hour journey back to the big city.

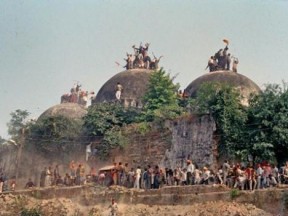

It was dusk when I reached office. I was greeted by a more grim and stony silence than I had endured in the bus. Everyone was there, at work, and no one spoke except when needed to. I got the news I was dreading to hear: the mosque was history, the Babri Masjid had been rendered into rubble. There was no need for me to file a story. I was advised to head for home.

I quickly read through all the creeds on the demolition and returned home quite disturbed. This shouldn’t have happened. It had been the Ramjanmabhoomi agitation of the late eighties that had first made me pick up a pen and write. Literally. And it had been that acerbic piece in a magazine that had got me my first hatemail, a threatening letter from an obscure Hindu hardliner group. To me all zealots were a threat to a civilisation of peace — Hindu or Muslim. The first had proved me right this time out.

Fuzzily, with a million thoughts racing through my mind, I tucked myself in. There were no blogs those days, my opinions remained with myself. I stayed alone and did not have either a television or a radio. I remained oblivious to what might have been happening around that night. After I readied myself and clambered down from my third floor flat the next morning, empty streets were all that I saw. The Left Front had called a bandh. Those days an LF bandh was more effective than clamping down a curfew. Everything would remain shut anyway. It had also been the same tactic that the Front had applied after Rajiv Gandhi had been assassinated in 1991. A bandh can also be a tool to control mobs.

I didn’t have a phone either this time. So office was in no position to contact me. I had to ring them up. A rickety Ambassador picked me up from my Salt Lake residence an hour later. To work, I went, all charged up.

What happened to me during the next few days was a lesson in journalism. PTI stories, at least in those days, were known for their straightjacket formats. No adjectives. No adverbs. Every quote attributed to a source, or dropped altogether. There was no room to whip up passion. If there was an antithesis to sensationalism, it was this. We could take the sting out of everything. At the helm of the regional desk was a man with nerves of steel, and who knew how to handle exigencies like this. Playing up a story is easy. Any idiot can do that. But to play it down, you need to be a good journalist.

There had been post-demolition violence in many towns and cities across India. Riots had broken out in Calcutta too. Those weren’t days of 24/7 television. Akashwani was for kisan bhais. Mobile phones and SMSs were only science fiction. And we were yet to know of the Internet and emails. But the riots had spread. And it hadn’t been because of a media which had done the dirty job.

For my part I knew what we had done. Everything had been reported, including the deaths. But the copies did not say members of which community were killed. And which community had killed them. It was about the deaths of people. And that is what a democracy should be — it ought to be about people.

Subir Ghosh is a New Delhi-based independent journalist and writer. He has worked with the Press Trust of India (PTI), The Telegraph, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), the Federation of Hotels and Restaurant Associations of India (FHRAI), and the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI). He specialises in Northeast affairs and is an advisory council member with the Centre for Northeast Studies (C-NES). He is the author of ‘Frontier Travails: Northeast – The Politics of a Mess’ and has won two national awards in children’s fiction. His interests include conflict, ethnicities, wildlife, human rights, poverty, media, and cinema. He blogs at www.write2kill.in