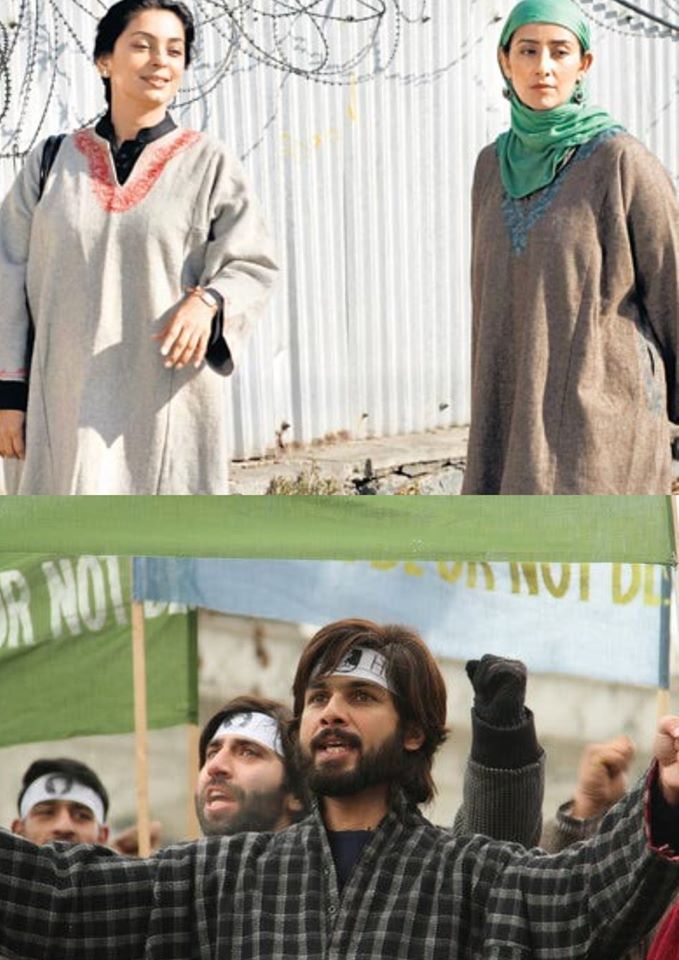

Onir’s anthology I Am (2010) remains one of the most deeply felt and insightful cinematic statements on Kashmir where Juhi Chawla’s Megha (a Kashmiri Pandit) and Manisha Koirala’s Rubina (a Kashmiri Muslim) connect after twenty years of estrangement amid barbed wires, abandoned, crumbling homes with bullet riddled walls and layers upon layers of anger and grief.

The Kashmir Megha returns to is not an Eastman Colour fantasy but a war trench where family outings to bustling cinema halls and organic human connections across religious divides have died an unnatural death and even a stroll in a street can spark an argument or something worse.

At one point Megha says to someone on the phone, “Paradise? Aake dekh lo.” She is angry even with the family she grew up around and whose elders she refers to as ‘Ammi’ and ‘Abbu.’ In the home of a relative who was killed during militancy, she brushes aside the comforting hand of Rubina, once her best friend. She releases the ashes of her father in a lake but realises at some point that she is not the only one who has lost a sense of home. That hers is not the only disenfranchisement. And that, for every Megha, there is a Rubina, dealing with her own loss of innocence in a war zone where a knock on the door can interrupt a meal or many lives. She realises that there is no survivor in a war where empathy for the ‘other’ is killed first.

This level of nuance was possible in the film perhaps because Sanjay Suri who produced the film saw the tragedy of Kashmir firsthand when in 1990, his father was killed in a terrorist attack. That the story of Megha and Rubina was not a one-sided , jingoistic account is to the credit of the film maker and Suri himself.

The cinematic gaze on Kashmir however has usually been cosmetic right from the sixties. A reimagining of Eden where meet cute moments in melodious songs unfolded during cycling and jeep rides, picnics and in and around jostling shikaras brimming with flowers and phiran clad beauties. Politics was not central to the narrative though in Raj Khosla’s Ek Musafir Ek Hasina (1962), there is a fleeting reference to the hero being sent to Kashmir to combat “rebels.” Mostly though, Kashmir was the setting for multiple versions of ‘Come September.’

And a love track even if between a local and a ‘pardesi’ did not address an inter-religious connection. In Jab Jab Phool Khile (1965), the shikara boy is simply called ‘Raja’ while in Ek Musafir Ek Hasina and Kashmir Ki Kali, the heroines are called ‘Asha’ and ‘Champa.’

In the seventies, Kashmir was a just a prop like that rose spangled cottage where the teen couple in Bobby (1973) is locked in temporarily to imagine multiple romantic ‘what ifs.’ Or that Shiva temple featured in the famous Jai Jai Shiv Shankar sequence in Aap Ki Kasam (1974) that actually became part of a five day Kashmir package.

In 1982, Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Bemisaal actually paid a tribute to the scenic beauty of Pahalgam with a song , “Kitni khoobsurat yeh tasveer hai.” Because perhaps to the unseeing eye, that is all the region was. A beautiful painting.

It was left to Ved Rahi in 1991 to take Kashmiris into account with a warm story of interfaith friendships in Doordarshan’s hit series, Gul Gulshan Gulfam.

By 1992, when Mani Ratnam decided to shoot Roja in Kashmir, there was no avoiding a new , shadowy protagonist. Terror. And though the story was framed in the context of two opposing ideologies about Kashmir, it was shot ironically in Coonoor, Ooty, and Manali without the input or contribution of Kashmiri voices.

Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s high octane Mission Kashmir in a way was reminiscent of JP Dutta’s Yateem where a young orphan is rescued by a conscientious law enforcer and the child has to at some point answer the big questions about identity.

Shoojit Sarkar’s 2005 film Yahaan, subverted the colour soaked romance trope set in Kashmir to show a beleaguered valley bleached of all light where an unlikely love blossoms nevertheless between an army officer significantly named Aman and a Kashmiri girl named Adaa. The plot though convoluted dared to imagine a possibility of peace and humanised the rebels and those fighting them , as also the women caught between them.

Rahul Dholakia whose Parzania retold the tragedy of the 2002 Gulbarg Society massacre in Gujarat, made Lamhaa in 2010 to narrate the multiple human tragedies unfolding under the shadow of the bayonet.

Samar Khan’s Shaurya (2008) was another important film about Kashmir as it juxtaposed the premise of A Few Good Men in the valley to tell the story of a Muslim soldier accused of killing his senior during a civilian raid. The whys and the hows are answered and the question asked just what is ‘shaurya’ or valour? The subjugation of the weak or the protection of the powerless?

Ashvin Kumar’s 2019 film No Fathers in Kashmir fought an eight month long censorship battle for its heartbreaking glance at the disappearance of the valley’s men from the lives of those who love them. Another 2019 film, Aijaz Khan’s Hamid saw the conflict in the valley through the trusting eyes of a child.

A few years back, Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider went where few film makers had dared to before.

Haider replayed keynotes from a classic Shakespearean dirge with a sly wink. So we were offered the jovial grave diggers. The sinner in a moment of redeeming prayer. The ghost who is not a ghost afterall but is Roohdar..the keeper of another man’s soul and all its agony. There is the undignified seducer with shifty eyes who cannot stay away from his brother’s wife. The disgraced mother so in love with herself that she cannot resist stealing a look at herself in a broken mirror in the burnt shell of what was once her home.

But the most important aspect of the story was the geographical context. An ideologically divided Kashmir (in the timespan of 1994-1995)that with its conflicted core becomes a mirror image of Haider who cannot accept anybody’s version of his reality.

The film then reimagines Hamlet in Kashmir with a play within a film set to Gulzar’s lyrics. Faiz’s poetry (Gulon mein rang bhare…Baad-e-Nau-bahar chale.. Chale bhi aao ke gulshan ka karobar chale) wafting from prison cells where a humanist who once honoured life more than taking sides..is now waiting to die and to be avenged. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, now played by vendors of Salman Khan’s films and sellers of dangerous secrets.

The real hero of the film however is the writing because of the dark, unexplored places it takes you to.

Co-writer Basharat Peer takes off from his searing book Curfewed Night to take us by the scruff into the interrogation centres reeking with pain, the cinema halls where against the backdrop of a foolishly jumping Salman Khan, stand prisoners of an undeclared war, in chains, waiting for a bullet or another indignity. Where identity is just a card and you must declare it satisfactorily in every street and checkpoint or you could disappear like the unaccounted for 8000 Kashmiris. The blindspot riddled Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act is brilliantly turned into a soliloquy as Haider stands in a street square to ask the question, “Hum hain ya hum nahin?” Are we or are we not? This is another, more angsty version of Hamlet’s cry of, ‘To be or not to be.’ So the all important question the film asks is, “What if you are not allowed to be? If everything you love is taken away from you? Do you avenge your losses?” Or as a wise patriarch played by Kulbhushan Kharbanda says in the film, would you rather find peace instead..by breaking out of the cycle of revenge.

There is Shakespeare’s Gertrude, or Ghazala played with relish by Tabu. A suppressed wife afraid of her husband’s idealism who then watches in horror as he is hauled away by the security forces and her home is destroyed in one body blow. She is also an unapologetic coquette whose redemption is a final hurrah, reminiscent of a similar climax in Gulzar’s Hu tu tu .

Shahid Kapoor’s Haider is far less complex than Hamlet though. He is just a grieving son looking for some answers and then revenge through the maze of relationships that stalk and disable him. What the film however did with partial success is to dispel the ideation of Kashmir as a land without living, breathing people. It asked us to remember that Kashmir is not just a single narrative told by a few but a story within a story within a story. And that every story matters. As does every single human life.

(Haider’s excerpts from a review previously published on Unboxed Writers)

**Reema is the editor and co-founder of Unboxed Writers, the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, a translator who recently interpreted Dominican poet Josefina Baez’s book Comrade Bliss Ain’t Playing in Hindi, an RJ and an artist who has exhibited her work in India and the US . She won an award for her writing/book from the Public Relations Council of India in association with Bangalore University, has written for a host of national and international magazines since 1994 on cinema, theatre, music, art, architecture and more. She hopes to travel more and to grow more dimensions as a person. And to be restful, and alive in equal measure.