*This piece was written on February 16, 2020

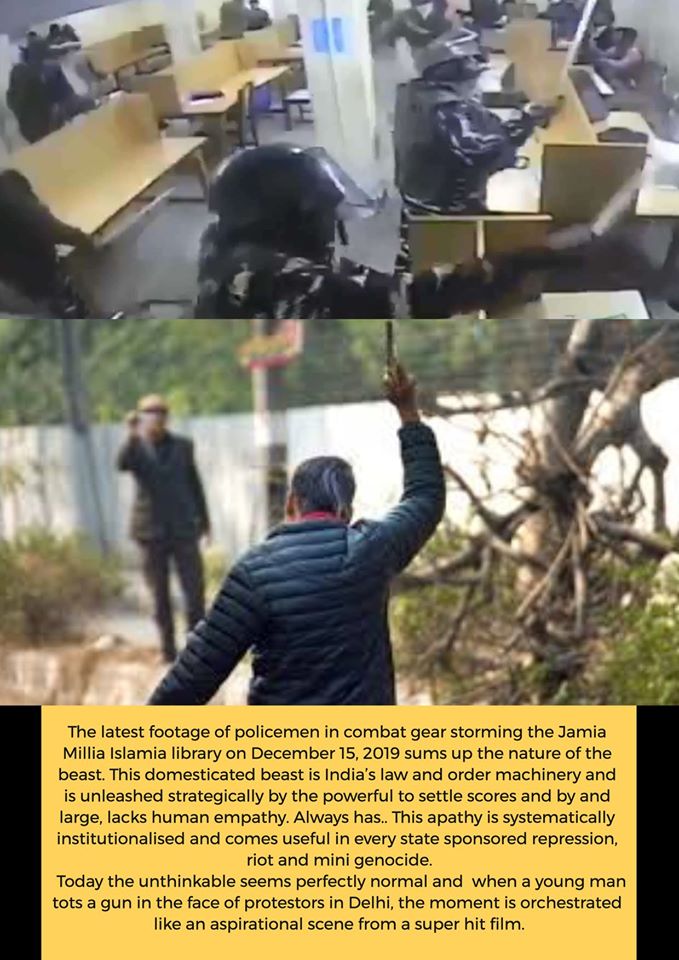

The latest footage of policemen in combat gear storming the Jamia Millia Islamia library on December 15, 2019 sums up the nature of the beast. This domesticated beast is India’s law and order machinery and is unleashed strategically by the powerful to settle scores and by and large, lacks human empathy. Always has.

In 1990, post the immolation attempt by Rajeev Goswami, a Delhi University student, a sudden bandh was called in my home town. On my way home from the University, I walked past a few loitering policemen one of whom looked at me and taunted, “Kyun tujhe nahi karna aatm dah? “ (Why, you don’t want to immolate yourself?)

Regardless of which ideological plank we occupied during that time, the sight of a student setting himself aflame on camera was horrific to all Indians. But the apathy in the police man’s voice was even more horrifying. So the fact that policemen barged into a university library to break the bones of young scholars is not surprising. This apathy is systematically institutionalised and comes useful in every state sponsored repression, riot and mini genocide.

What has changed though is the nature of the Indian citizen who now watches the country bleed from a million arteries, with a shrug. And sometimes with a smile.

After a friend posted the Jamia video, someone commented on her timeline, “Serves them right for damaging public property.” Another one said, “what a specious (sic) library..when so many people dying in cold on roads.”

I am not sure, if as a nation we know the difference between right and wrong any more.

Remember that viral video of a little girl whose baby mouth spit out the slogan .. ‘desh ke gaddaron ko..’? This was possibly a school event. The adult fussing over the child’s mike was either a parent or a teacher. This is where we are now. At a point where a school with state approval staged the destruction of Babri Mazjid while kids in another school were slapped with sedition for daring to enact an anti-CAA play.

A large number of us are even happy that this kind of policing is teaching important lessons to those still dreaming of a democratic and secular country. Who wants these ideals anyway? The lynching videos should have taught us something by now.

Today the unthinkable seems perfectly normal and when a young man tots a gun in the face of protestors in Delhi, the moment is orchestrated like an aspirational scene from a super hit film.

But there really was a time, when India, despite its fault-lines aspired to the highest ideals enshrined in its Constitution. When it had not yet lost its innocence collectively. Recently, journalist Ravish Kumar paid a tribute to that lost innocence when he shared a few snapshots of flowers with this caption,“Dekho maine dekha hai ye ek sapna..phoolon ke sheher mein ho ghar apna.” The song spoke to my generation because it conjured an idyllic world where we could build something without fear.

This was a significant wish for those of us who had experienced the horrors of Partition second hand. Through our grandparents or parents who had come to India with empty hands and severed roots to build a home again. To find some version of a “phoolon ka sheher.”

My mother was almost the same age during Partition as the young child who screamed into the mike, “goli maaro salon ko.” Yet, she never brainwashed me because she had seen how destructive hate can be. I am sure she can identify with the mother who brought her four month old baby to the Shaheen Bagh protest in Delhi. The fear and desperation that must have driven this mother can be understood only by a refugee spirit that knows what it is to lose everything.

I grew up in terrorism scarred Punjab where even a bus ride from Patiala to Delhi was shadowed with the possibility of an attack. But still, this was an India where hate had not yet been normalised in conversations, in entertainment and in journalism. We laughed, cried and got angry together. Some of the most important protest films of the time were funded by NFDC and made by the alumni of FTII. Our cultural institutions still had agency and freedom.

Our nerves collectively thrummed to a Shiv Kumar Sharma santoor tune. The one that Yash Chopra used in Silsila to evoke restful winter mornings and the possibility of serendipity.

My school screened Sai Paranjpay’s Chashme- Baddoor for its outgoing seniors, perhaps to reassure them that love, friendship, a job were achievable goals. And if life got tough, we could always play Mehdi Hasan’s, “Yeh dhuan kahan se uthta hai”. No questions asked.

It was normal for Ghulam Ali to sing “Chupke Chupke,” a ghazal penned by Indian freedom fighter, poet and parliamentarian Hasrat Mohani .

Or for us to hum,“Ye dil ye pagal dil mera,” a ghazal penned by Pakistani poet Mohsin Naqvi. We mourned him when he was killed by the Taliban in 1996. Thinking this would never happen to one of our own.

Jagjit Singh sang Faiz.

Taj Mahal was not yet suspected to be a Tejo Mahalya but was both a love poem written by Shakeel and a protest anthem by Sahir.

Decades before a term like Love Jihad was coined, a 12 minute qawwali written by Sahir in PL Santoshi’s film Barsat ki Raat proclaimed, “Ishq azaad hai Hindu na Mussalman hai ishq.”

Yash Chopra blistered by the hate he saw during Partition, made Dharam Putra in the fifties to show us the difference between culture and bigotry. To say, through a Sahir qawwali “Tum Ram kaho ke Rahim kaho, matlab to usi ki baat se hai.”

We tuned into All India Radio Ki Urdu Service to listen to ‘Haq Ali,’ a haunting Sufi qawali in the voice of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan from the Yash Chopra production Nakhuda.

We drank in the symphonic beauty of the Hall of Nations in Pragati Maidan when Chopra shot his film Trishul’s climax here. The same Hall of Nations that was reduced to a rubble a few years back without an explanation.

And that is perhaps how our formative years felt different. Life then had more space for us to come together and rejoice in the possibility of beauty.

Oh, we were not perfect but we also knew, we would not stop trying. We were unaware as yet of how hate can be streamed into our blood stream via television screens, social media platforms, WhatsApp forwards.

How an Iqbal poem, and even a Faiz can be “othered” in a country where Sahir equated Allah with Eshwar and Eshwar with Allah.

I often wistfully recall a key scene in Phir Wohi Talaash, a 90s TV show based on Urdu and Hindi writer Revati Sharan Sharma’s story. That scene where the protagonist Padma cites Ghalib to her best friend Shehnaz thus, “giri hai jis pe kal bijli vo mera ashiyan kyuun ho.” Why must my home be stricken by lightening?

That sense of home? It once belonged to all of us. Not anymore. The most privileged amongst us are now okay with the fact that an entire valley is under lock and key. Or that detention camps are being built to lock millions more across the country. Or that children now talk of bullets and bloodshed.

Nationalism now means cheering from sidelines when a policeman beats a young woman to a pulp and taunts, “Aa.. main deta hoon tujhe azadi.”

As Javed Akhtar wrote portentously, “Yeh kahan aa gaye hum yun hi saath saath chalte.”