In the opening credits of MS Sathyu’s Garm Hava, you hear Kaifi Azmi’s lament,

“Taksim hua mulk toh dil ho gaye tukde; Har seene mein toofan, wahan bhi tha yahan bhi

Har ghar mein chita jalti thi, lahraate the sholay; har shahar mein shamshan, wahan bhi tha yahan bhi

Gita ki koi na sunta, na koi Quran ki sunta;

Hairan sa imaan, wahan bhi tha yahan bhi.”

(a storm raged in every heart…over here and there

a burning pyre in every home..over here and there

every town a crematorium, over here and there

Neither Gita no Quran were heeded

just a stunned conscience, over here and there)

And then we see a Karachi bound train chugging its way out of Agra as Balraj Sahni’s Salim Mirza waves his hand wistfully. On his way back home, he tells the tonga driver that he has just bid farewell to his sister and her children. He says, “kaise hare bhare drakht kat rahen hain iss hawa mein ‘ (Such green, imposing trees have fallen in this wind).

The tonga driver responds, “badi garm hava hai..badi garm,..jo ukhda nahin to sookh jayega, ” (These scorching winds…those who won’t fall, will wither) and Salim Mirza, the idealist who thinks, the assassination of Gandhi will snuff out communal hatred, says nothing. He doesn’t know it yet but he is the green, imposing tree about to be tested by the merciless winds of change, hate and loss.

**

Garm Hava, you instantly understand, is not a Partition film about the Partition. It is not one of those films where a victim is set up as a victim with broad gashes of tragedy and violence hounding him. It is not about bloodshed, violence but the dehumanisation of a decent man who just wants to live peacefully with his faith in humanity intact.

**

Nothing in the film is staged to say, “Look at this..such a tragedy..this man is now in a minority in his own watan.” But slowly but surely, life as he knew it begins to wither. Salim Mirza runs a leather footwear factory and needs money to start work on a big order but he is refused loans. His ancestral haveli is now being eyed by someone who was once a friend. His elder brother Halim ( who aspires to be the leader of Indian Muslims, leaves for Pakistan with his family. His son Kazim leaves unwillingly because he is engaged to Salim’s daughter Amina (Geeta Siddharth) and wants to return as as soon as possible to solemnise the wedding. There is Salim’s clear-sighted and matter of fact wife (Shaukat Kaifi) who overhears tragedy before it arrives. Salim’s composure and optimism remains unshaken through the loss of his business and home, the departure of his disillusioned elder son to Pakistan, a humiliating accusation of being a spy and the cruel heartbreaks his daughter is put through.

But Garm Hava is finally Amina’s tragedy whose heart is partitioned twice and love cruelly snatched. While Salim has the resilience and the quiet courage to rise from the ashes. it is Amina who cannot withstand the loss of hope.

**

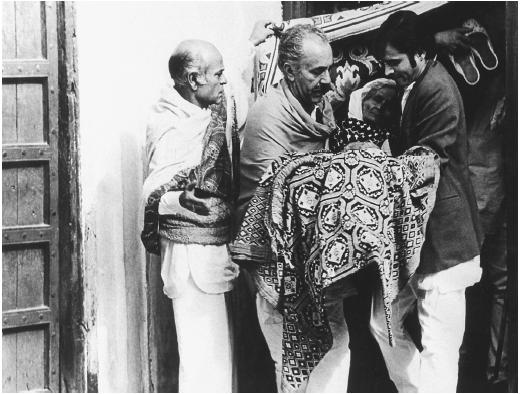

Garm Hava is also the tragedy of the matriarch who cannot understand why she has to leave the haveli she came in as a child bride. One of the most moving scenes ever filmed in Hindi cinema is when the family is leaving their haveli forever for a rented house and the old woman hides in a shed, and is then carried out physically from the house, crying pitifully as a living metaphor for every single person who was disenfranchised and uprooted during and after Partition.

**

The film is also the tragedy of a nation that continues to be partitioned daily in some form or another. and where micro realities are sacrificed daily for a shining national identity without diversity.

Ishan Arya’s gritty and yet sensitive cinematography (watch the scenes between Amina and Shamshad at Salim Chishti’s dargah and at Taj Mahal) has texture and raw emotional power. The writing by Kaifi Azmi and Shama Zaidi fleshes out the powerful story by Ismat Chughtai and gives us a narrative that despite its almost unbearably honest look at a divided nation, speaks of hope and endurance.

**

Balraj Sahni’s Salim Mirza is one of the ten most unforgettable characters in Indian cinema and in every line of his body and in his face, you can read gentle humanism and a certain innocence that can withstand anything. Even the unimaginable. Watch this film for Farooq Shaikh’s debut, Geeta Siddharth’s wrenching portrayal of Amina but most of all for Sathyu’s retelling of a story that deserves to be heard again. And again.

with

The New Indian Express

Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, Bangalore, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, an artist, a former RJ and a mother. She dreams of a cottage of her own that opens to a garden and where she can write more books, paint, listen to music and just be.

with The New Indian Express

with The New Indian Express