Not in my wildest dreams had I imagined that driving across a frozen mountain pass at 13,714 feet, one cold, grey afternoon, I would come face to face with a young soldier. Who would teach me a lesson for life. That a soldier doesn’t die when a bullet whips into his head, piercing his woolen balclava. He doesn’t die when he falls before an enemy machine gun, staining the snow with his warm blood. Or even when he is left to merge with the elements on a barren mountain pass. It is only when we forget their acts of bravery that soldiers die. And, though we have killed many that way, Rifleman Jaswant Singh Rawat is one of the few who live on.

At the treacherous heights of the Sela pass (on the Indo-China border), a perennial mist envelops the bends in the road and a deep silence permeates the lonely mountain. This is where unprepared Indian soldiers fought a war with the Chinese in November, 1962, in freezing temperatures, wet shoes and thin sweaters (thanks to unworthy commanders – which is such a disgusting story that we’re not going there at all). On the pass stands a lone shrine called Jaswantgarh that holds the memories of Rifleman Jaswant, Maha Vir Chakra (posthumous) of 4 Garhwal Rifles.

Those who want to see Jaswant make a rather long journey through the forests of Arunachal with orchids drooping down from lush green trees. Then going across the claustrophobic Tenga valley, they climb the winding path to Bomdila and drive down to beautiful Dhirang. Then up again, passing pink-cheeked babies with running noses strapped onto their mothers’ backs, they cross the tankha-adorned, mist-blurred ‘Welcome to Tawang’ gate. Finally they circle the frozen Sela lake and get onto a narrow 12-foot track cut into fallen snow and reach Jaswantgarh.

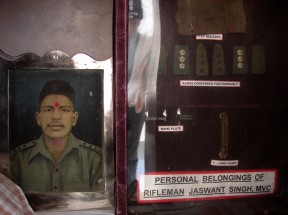

This is where rifleman Jaswant Singh was shot by the Chinese when he attempted to stop their intrusion with just three hand grenades in his pocket. Foolhardy thing to do but young heroes in uniform do this kind of stuff all the time. His worldly possessions are kept in a small room with a narrow, neatly made bed. A fresh towel, an HMT watch on a side table, a cheap plastic framed mirror, a pair of shoes and an olld woolen cap riddled with bullet holes, all that Jaswant left behind is right there. Actually, it doesn’t look like he has left either. His linen goes for a routine wash, his towel is changed regularly and soldiers who polish his shoes claim that they are often found covered with mud, a sign that he has been walking around at night. The myth goes that convoys in blizzards have seen Jaswant directing the vehicles through the treacherous bends. Eight promotions have come to him after death and Jaswant is now a Captain. The hefty sardars of the Sikh regiment stationed there get him the first thali of steaming hot food from the langar. And men sitting with AK 47s draw warmth not just from their Old Monk rum but also his reassuring presence.

For nearly an hour, I sit in his room and read the letters that have come to him. They talk about family problems, unemployment, failed crops, land disputes, poverty, lost promotions, life threatening illnesses. The list of sadness is endless. A young boy is desperate for job, a soldier’s wife is childless, a farmer has lost his only son. There are invitations to weddings and ‘namkaran’ceremonies, prayers, wishes and pleas for help. Mail has been coming to Jaswantgarh for years. It comes from people seeking inspiration to live, strangely enough, from a dead man. A big mountain dog sleeping there, twitches an eyebrow at my presence. “Relax! All is well. Go back to sleep,” I tell him and he obediently shuts his eyes again. A Sikh Subedar Sahab potters around, happy to have some company. “Sometimes months pass before we see a new face,” he says, offering us tea and hot pakodas. We chat for a while and then it’s time to go.

In the hassle of putting together scarves, caps, gloves and cameras and ensuring the kid has used the loo one last time, I forget to say a final goodbye to the soldier with whom I seem to share a bond and a last name. The car is moving, we have a long way to go and I can’t be a sentimental fool and insist I have to go back, if only for a minute. I bite my lip and look out of the window. We are crossing a lone signboard buried in the snow. “When you go home, tell them of us and say. For your tomorrow, we gave our today,” it says. Might have been a trick of the mind but leaning against it, I see a slim Garhwali soldier with a smile crinkling his brown eyes. He is looking straight at me. On his head there is a woolen balclava riddled with bullet holes. “Yes Jaswant I’ll tell them that. You just live forever!” I mumble as the car takes a turn and he disappears around the bend.

War citation

On 17 November 1962, 4 Garhwal Rifles was occupying a defensive position near the Nuranang Bridge in NEFA. Rifleman Jaswant Singh Rawat’s company was subjected to a series of attacks by the Chinese force. Jaswant Singh and two other men volunteered to go and destroy the enemy Medium Machine Gun position. They crawled forward and within 15 yards of the gun, hurled grenades on it killing two Chinese and badly wounding the others. Jaswant Singh then snatched the Medium Machine Gun and started to return to his position. The enemy opened automatic fire from close range. Jaswant Singh was hit in the head and died on the spot still holding the Medium Machine Gun. For the exceptional courage and initiative shown by Rifleman Jaswant Singh he was awarded the Maha Vir Chakra posthumously.

I salute you with heartful pride my beloved brave soldier Jaswantji.May your blessings be always with each and every soldier who are fighting to protect mother India.I bow my head before your memoirs

नमस्ते बहनजी.

आपका लेख पढ कर बहुत खुशी हुई और मन प्रेरणा व अभिमान से भर गया. भगवान की कृपा से आपके हाथों और प्रेरणादायी लेखन हो यही सदीच्छा.

ई.स. २०१२ की दिवाली के लिए हार्दिक शुभकामनाएं!

यह लेख पढने के बाद ही अरूणाचल जाने की हमारी इच्छा और प्रबाल हुई. और गत मई २०१३ में मैं, मेरी पत्नी और हमारे दो बेटे (६ व १०) अरूणाचल का अद्वितीय सृष्टिवैभव का आनंद ले आए. हर एक जवान की समाधि के दर्शन करते हुए आपके इस प्रेरणादायी लेख का स्मरण होता रहा.

मनःपूर्वक धन्यवाद. ॥ जय हिंद ॥

(1) http://sdrv.ms/115xNKJ | (2) http://sdrv.ms/10Inxm2 | (3) http://sdrv.ms/10InNS5 | (4) http://sdrv.ms/10Io0EQ