It is neither compulsory nor mandatory but I feel the need to make this admission: I am not an outsider. Though not of Kannada origin, I have been a resident of Bangalore/Bengaluru since the start of the 80s. That’s been over three decades, during which I have lived, worked, married, learned the language, savoured the local cuisine and crafted a most satisfying life for myself in the city formerly known as the Garden City. And most importantly, as the author of this monograph states in another context: I may not be a mannina magalu but my identification with Bangalore is unconditional.

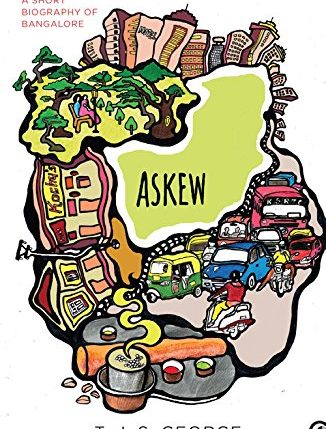

That disclosure over, let us move on to veteran political journalist, author, biographer TJS George’s contribution to Aleph’s city monographs, Askew a short biography of Bangalore . After the monographs on Madras, Bombay, Calcutta, New Delhi and Patna comes the Bangalore one. Actually, the title gives much of it away; George places the image of a city that’s gone off the rails under a dome, trains a microscope on it and proceeds to tell us just why it has gone off the rails.

He arrives at Bangalore taking a rather digressive route via NYC, Hong Kong, Bombay and Patna. But when he does arrive in Bangalore, he wastes no time in telling us that this used to be a city at peace with itself, now it is askew, knocked off balance by the weight of its own growth. The buck for a lot of what ails the town-turned-city is laid at IT`s doorstep, the remaining portion shared equally by the politician and the bureaucrat. He`s right, of course. Wittingly or otherwise, the influx, the growth has been an uncontrolled one and of course, infrastructure falling woefully short, the result is there for all of us to see and some of us to sadly, experience. An almost complete lack of coherent city planning adds to the confusion. The citizens who previously largely adopted a chalta hai attitude, now have honed their activism but the powers-that-be have become brazen, shameless and really couldn’t care less.

In my Bangalore, says George with a faint touch of wistfulness, the traffic was civilized, the parks were green and the trees full of birds. This then is a look at old Bangalore. Grouses familiar to most of us are brought up for fresh if frustrated examination: the noise, the traffic holdups, the power outages. The haphazard numbering of buildings on our roads, so much so that 166A sits next door to No 171 and no one does a thing about it. The fine dust of continuous building that forever hovers over what was once a fine city.

The narration is imbued with the author’s acerbic style. We read of many things that were and are intrinsic to the city like its patriarchal trees, its cultured living and the Dhritarashtrian hold by the real estate mafia, we rediscover a charming old fact, that RK Narayan joined the names of two large precincts of Bangalore, Basavangudi and Malleswaram, to form Malgudi, the place he set his stories in.

All the usual suspects are in here: the founder of Bangalore, Kempe Gowda; Infosys founder Narayana Murthy, his author wife Sudha Murty, their son Rohan Murty; the absconding tycoon Vijay and his son Siddhartha Mallya; Ranga Shankara’s Arundathi Nag; the late great writer UR Ananthamurthy; Janaagraha’s Ramesh Ramanathan; civic evangelist V Ravichandar; entrepreneur turned politician Nandan Nilekani; Suryanarayana Hedge of Veena Stores; the Maiyas of MTR; Radhakrishna Adiga of Brahmins’ Coffee Bar; Prem Koshy of the fabled Koshy’s, and suchlike.

A city, says the author, is a living, throbbing organism with a soul of its own, and…. a thinking mind. One is hard put to define the values of a city which went from pensioner’s paradise to concrete maze without ceremony. George writes of the firm grip the underworld has on Bangalore but we the citizens are not exempt; he rues the fact that the racist element that lies submerged in all peoples waiting for opportunities to surface, has found and continues to find many opportunities to surface in our city.

The author assures us that every generation looks back over its shoulder and laments the passing of a better time. He also winds up the account praising citizen activists who, he says, are canny enough to avoid confrontational ways; accepting that the plundering class needed no reasons for plundering, only pretexts, the activists are looking to reduce those pretexts. Therein lies hope for a course correction of the city, according to him. But by and large, it is a requiem for Bangalore that George writes, one that adopts a matter-of-fact style, is not imbued with any undue sentimentality and is backed by statistic after dismaying statistic.

I loved the story of what Kempe Gowda’s mother told him when he set out to set up a new city. But you’ll need to read the book to find out that pertinent piece of advice for yourself. Suffice it to say, we the people of Bangalore have overturned that advice on its head. And we are paying for it.