Very rarely does a film become a visual sock in the gut like Pather Panchali or irrevocably changes the way we think of cinema. The images linger. An unloved old woman trapped in her impoverished life, singing a wedding song, longing for human contact, and then one day deciding that she has had enough. She dumps her belongings on a nervous kitten, throws the wiggling little thing on the ground and walks away while the mistress of the house watches on with quiet indifference.

And then the almost unbearable drama of a little girl trying to stop the old woman. And then life going on like it always does even post the biggest severings. The kittens are back at play, and the little girl is sweeping the courtyard.

And we learnt that cruelty is not always obvious violence. Cruelty is a lonely old woman being treated like she doesn’t exist. We are cruel when we withhold kind words and empathy. The film spiralled into our unlit corners to show us who we become when we are denied the satiation of basic needs. The cruelty birthed by lacks. And yet the grace inherent in children when they make the most of the little , find joy and love, chase trains, watch rain as it paints circles on lily ponds, and find safe spaces to be themselves.

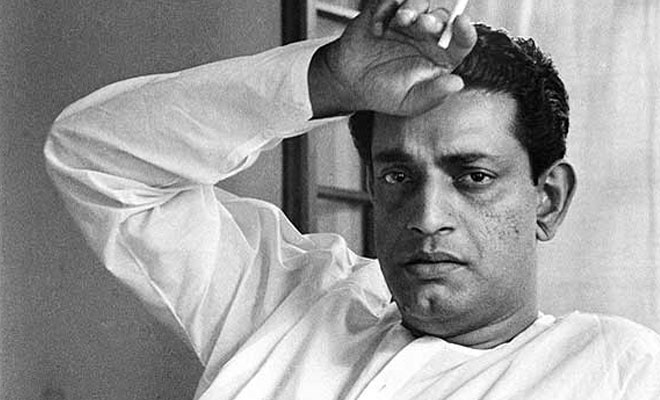

On May 2, Ray would have been 93. He made Pather Panchali (1955) when he was in his mid-thirties. And this film didn’t come from nowhere to alter cinema forever. Ray was not a nobody. He was the grandson of Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, a multifaceted writer, illustrator, publisher, astronomer and a leader of the Brahmo Samaj. His father Sukumar Ray was well-known for his quirky rhymes and children’s literature.

Ray would carry forward this creative effulgence in everything he did. His years at Shanti Niketan would expose him to the brilliance of Nandalal Bose and others. His illustrative and graphic work at D J Keymer was indicative of his unfurling visual sense. His book covers for Signet Press show his flair for emotive images, something that his cinema would celebrate. It was here that he worked on the abridged version of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s Pather Panchali. As he designed the cover and illustrated it, he felt drawn to the idea of filming the images. His appreciation of world cinema during a visit to London, where Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thief deeply impacted him, a meeting with Jean Renoir, all conspired to seed the ground for Pather Panchali’s success.

Yet the film began in obscurity and with unknown actors and little-known technicians like cinematographer Subrata Mitra and art director Bansi Chandragupta, both of whom would gain international recognition for creating a vividly real and yet magical visual vocabulary.

It took him three years to complete the film. The appreciation was instant, and yet the snobbery of peers like François Truffaut would result in snide remarks about peasants. But these were minor asides. What Ray had done was to make image, the primary story-teller and to erase the line between the real and the cinematic. Added to this was his uncanny ability to move, jolt, purge and elevate the human spirit with the simplest of scenes.

The old woman in Pather Panchali being carried for cremation, with a wedding song in her own voice playing in the backdrop. A few trinkets stolen by Durga found after her death. Charulata on a swing where we see the liberating motion of the swing. She watching the world go by from her insulated home, her face a montage of unlived joys, loneliness and amusement.

The tragic arrogance of the music loving zamindar of Jalsaghar and his final rush of pride summed up in a bag of coins. There are so many Ray films. Moments that till date stun you with lyricism, emotional depth and a quality that is pure magic.

His legacy goes beyond cinematic genius. It is about a wildly gifted man’s attempt to make us see the unseen, feel the indescribable and to understand that life with its searing lows and sublime highs, is the most beautiful when in a swaying field of utter silence, two children wait for a train to zoom into view.

The story was earlier published in The New Indian Express

http://www.newindianexpress.com/entertainment/hindi/A-Ray-of-Light/2014/05/05/article2206756.ece1

Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, Bangalore, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, an artist, a former RJ and a mother. She dreams of a cottage of her own that opens to a garden and where she can write more books, paint, listen to music and just be silent with her cats.