The heart of Ranga Shankara is unusually quiet except for the insistent pulse of “Akbar bhai? Arre, lightwale Akbar bhai?” The auditorium is empty in the hours preceding the second show of Dayashankar Ki Diary, a play from the bouquet that Mumbai’s iconic theatre group Ekjute has brought to Bangalore for the first time.

The heart of Ranga Shankara is unusually quiet except for the insistent pulse of “Akbar bhai? Arre, lightwale Akbar bhai?” The auditorium is empty in the hours preceding the second show of Dayashankar Ki Diary, a play from the bouquet that Mumbai’s iconic theatre group Ekjute has brought to Bangalore for the first time.

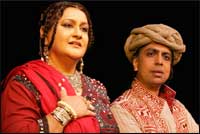

Unlike people who go to an auditorium to only watch a play and have no awareness of the space beyond the moment when the curtain falls, actors and serious theatre practitioners have a certain etiquette and respect even when they are alone in a performing space. They keep their voices low, their manner understated. I watch Nadira Zaheer Babbar giving an interview to a journalist but her voice is close to a whisper. The visceral lead actor of Dayashankar Ki Diary, Ashish Vidyarthi is strolling the stage peacefully at a distance, possibly sorting his inner world for the demanding performance ahead.

Then the much in demand Akbar bhai appears and for the first time I hear Nadiraji’s voice, “Ek light ki roshni kam thi aur mera actor andhere mein khada tha (A light was dim and my actor was performing in the dark).” The work of a mother never ends, I realise. When it is my turn to speak with her, it is obvious that she is tired. It has been a long day but she is still all gentle radiance and warmth and even apologises for the rather insignificant fact that I have had to wait. This coming from a woman who has spent 30 years or more working tirelessly as a writer, actor, director, mentor and yes, mother at Ekjute, the theatre group she founded in 1981.

Over the last 30 years, Ekjute has created a legacy of over 60 plays including classics like Sandhya Chhaya, Ballabpur Ki Roop Katha, Shabash Anarkali, Bharam Ke Bhoot and Begum Jaan and many others that she has penned, acted in and directed.

Is she aware of the extent of her work and just how many people she has impacted with it? She answers, “I did not begin with the intention of creating a legacy. I never thought I would start writing. Or direct. Or do theatre workshops. Or become a doorway to theatre for scores of young strugglers who come to Mumbai. I feel happy when young people who have been initiated in theatre by us, come back to do their bit even though they have made it big in television or movies. What is important that Ekjute has consistently worked towards a certain quality. We have never compromised that. I don’t want to single out theatre as a tough discipline to survive in. It is hard for all the arts to exist but we have survived, arrived and made it on our own merit.”

Is she aware of the extent of her work and just how many people she has impacted with it? She answers, “I did not begin with the intention of creating a legacy. I never thought I would start writing. Or direct. Or do theatre workshops. Or become a doorway to theatre for scores of young strugglers who come to Mumbai. I feel happy when young people who have been initiated in theatre by us, come back to do their bit even though they have made it big in television or movies. What is important that Ekjute has consistently worked towards a certain quality. We have never compromised that. I don’t want to single out theatre as a tough discipline to survive in. It is hard for all the arts to exist but we have survived, arrived and made it on our own merit.”

The fact that she is the daughter of Syed Sajjad Zaheer, a man who studied law at Oxford, became a barrister and yet was one of the founding members of the Communist Party of India and an integral voice of the Progressive Writers Association, the Indian People’s Theatre Association and the Afro Asian Writers’ Association, has impacted her hugely. Her mother Razia Sajjad Zaheer was an Urdu writer and Nadira says, ‘‘Ofcourse, the entire line of thinking in my work comes from how I was raised. The thematic message of my plays (Ji Jaisi Aaap ki Marzi, Dayashankar ki Diary, Yaar Banaa Buddy etc) has a lot to do with the values I grew up with.”

The voices of the dispossessed, the marginalised, the unaccounted for find a space in her work and even though she graduated from the National School of Drama (NSD) with a gold medal, went to Germany on a scholarship and worked with international giants like Peter Brook, it was fated that she would return and root her craft in her need to say something about the milieu she calls her own.

30 years is a long time in the life of a nation and Nadiraji says, ‘‘Yes, a lot has changed. Fundamentalism has increased. And even on a smaller scale, log tayyar bathe rehte hai bura manne ke liye (people are always ready to take offence). Even in families today, the level of tolerance has decreased. Koi sunna nahin chahta (nobody wants to listen). Relationships and marriages break up far more easily. There is corrosion and decline in etiquette and the level of courtesy you come across in airports, roads, shops, waiting rooms in hospitals, reception areas, offices, everywhere.”

She continues, ‘‘It matters more which car you emerge from. What clothes you wear. What connections you have. What language you speak in. We feel small and ashamed, speaking our own language. Its not cool to speak in our mother tongue. The decay in values is stark but there is also some amount of good. The dispossessed are getting a voice. Education is becoming a priority even for the poor. The so called backward classes are defining their identity through arts, crafts and even theatre.”

For those not aware of the extent of her work in theatre, her presence in Gurinder Chaddha’s Bride And Prejudice is a definitive keynote. And Nadiraji does not mind it. Says she,‘‘I don’t feel bad when people come and tell me they loved me in that movie..and why don’t I do more work? This is a developing country where most people are preoccupied with earning two square meals. Who has any energy to spare to the arts? How many people know about the work of Ravi Shankar or Amrita Shergill, even?”

For those not aware of the extent of her work in theatre, her presence in Gurinder Chaddha’s Bride And Prejudice is a definitive keynote. And Nadiraji does not mind it. Says she,‘‘I don’t feel bad when people come and tell me they loved me in that movie..and why don’t I do more work? This is a developing country where most people are preoccupied with earning two square meals. Who has any energy to spare to the arts? How many people know about the work of Ravi Shankar or Amrita Shergill, even?”

Many years ago, she had directed a television serial called Titliyan but never returned to TV because, “These days, they are making serials about matriarchs and I get many offers to play daadis and naanis. The money is tempting but I can’t spare the hours that television requires. “Beta, mere haathon se bani kheer kha le..yeh dialogue bolne main kyon jaaon? (Why should I take up mundane work?)”

What satisfies her most today is the strides being taken by Ekjute Young People’s Theatre Group, of which her son, actor Arya Babbar is a big part. She is also completely supportive of the corporatisation of theatre and says, “I see nothing wrong in it as long as it does not affect the spirit of theatre. I am done with theatre being projected as an impoverished, gareeb medium. It is time, theatre respected itself. Yes, it is tough if you stop selling yourself short but in the end, those who want to work with you will work with you, anyway.”

She recalls how nearly 18 years ago, Ekjute decided that its team would no longer travel in second class trains but will demand air tickets, decent, clean accommodation and proper meals from those inviting them to perform in different cities. “These are some basic things that theatre artists do without even after working for ages,” she says.

Before I can ask her anything more, a few young actors surround her. There are hugs, squeals of recognition and some touch her feet. Before she is lost to me in the collective embrace of her extended family, she has one last thing to say, “If you believe in yourself, continue doing what you are doing. Hang on. Yes, things will get difficult but remember not to take short cuts and also that the tortoise wins if it keeps walking.”

Before I can ask her anything more, a few young actors surround her. There are hugs, squeals of recognition and some touch her feet. Before she is lost to me in the collective embrace of her extended family, she has one last thing to say, “If you believe in yourself, continue doing what you are doing. Hang on. Yes, things will get difficult but remember not to take short cuts and also that the tortoise wins if it keeps walking.”

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight. (http://www.flipkart.com/perfect-eight-reema-moudgil-book-9380032870) . More on Story Wallahs. Other books by Unboxed Writers in our Store