Draupadi: “It’s begun. They are already preparing, they have decided on war, they know there will be war. But why, then, did they not tell me that? Why did they make me believe it is my decision, my doing? Why?

Draupadi: “It’s begun. They are already preparing, they have decided on war, they know there will be war. But why, then, did they not tell me that? Why did they make me believe it is my decision, my doing? Why?

Kunti: “Five splendid sons. The sons of Pandu, that’s what they called them. Pandu’s sons! And I could never claim my own son. “

Duryodhana: It was for this that he had been born – to come and stand here, in the dirty waters of a lake and be wounded, cold and alone. To know that this was the truth and the rest but a dream out of which he had now been awakened.

These are excerpts from three searing short stories (And what has been decided?, Hear me Sanjaya and The Last Enemy) by novelist Shashi Deshpande that she based on the Mahabharata and three of its monumental characters. She wrote not about the familiar operatic notes in the epic but about the inner lives of Draupadi, Duryodhana and Kunti as they swim through raging fires of ambition, taste bitter betrayal, suffer death of loved ones and the loss of innocence. And find no redemption and no closure as they forever mourn irrevocable changes caused by an inexorable chain of cause and effect within and without.

Recently, Chimeras, a theatrical adaptation of the three stories was staged at Bangalore’s Ranga Shankara. Chimeras, directed by Srikrishna S, interpreted the text in an unusual way by layering it with Bharathanatyam, Kalari, Chau, Indian contemporary dance. What the play did effectively was to stay true to Shashi’s attempt to pierce the myths and lore surrounding Draupadi (played by Surabhi Herur), Duryodhana (Sanjeev Nair ) and Kunti (Madhavi Sahu) and show us their humanity. Chimeras was produced by Version One Dot Oh! (VODO), an amateur theatre group started in 2003 that has over the years staged over 80 shows of 15 different plays.

Recently, Chimeras, a theatrical adaptation of the three stories was staged at Bangalore’s Ranga Shankara. Chimeras, directed by Srikrishna S, interpreted the text in an unusual way by layering it with Bharathanatyam, Kalari, Chau, Indian contemporary dance. What the play did effectively was to stay true to Shashi’s attempt to pierce the myths and lore surrounding Draupadi (played by Surabhi Herur), Duryodhana (Sanjeev Nair ) and Kunti (Madhavi Sahu) and show us their humanity. Chimeras was produced by Version One Dot Oh! (VODO), an amateur theatre group started in 2003 that has over the years staged over 80 shows of 15 different plays.

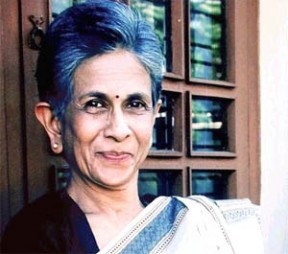

Shashi Deshpande, author of 10 novels, Sahitya Akademi and Padma Shri winner has no space in her head for hectic self promotion. She does not google herself, has no desire to create a custom-designed presence on the Internet and has never had a public relations machinery working to promote her work. And yet, her books find an audience and her stories, an answering echo as when the team at VODO came across the three mentioned above and connected with the raw emotion in them.

The earlier version of the play however had Sita’s monologue instead of Duryodhana and Shashi says, “When I saw the play for the first time, they had Sita instead of Duryodhana and I somehow felt it didn’t fit. Now they have all three Mahabharata characters and it is much better. They have used the stories almost verbatim, but the actors infuse the words with the soul and the personality of the person.”

And what germinated these stories? She answers, ‘‘I got interested in these characters when I thought of Amba and of how the character is almost ignored except for her dying and being reborn as Shikhandi who kills Bhishma. I saw her tragedy clearly. Then I wrote Sita’s story . Draupadi’s came out my indignation that she has been saddled with starting the war. Really? When did a woman have so much power?”

What her story peels off from the legend of Draupadi is the label of the woman who laughed at the wrong moment, got angry at the wrong men, suffered dishonour and refused to forget it. Was she the reason why the Pandavas went to war with the Kauravas? Would the war not have happened had she not been dragged out and violated before her husbands who had lost her at a game of dice? Shashi’s story recognised her as a woman who was an unwitting pawn in the game of power and was made into a convenient excuse to justify a war that would destroy empires and leave nothing in its wake.

Shashi reads the mind of the woman who married a young archer she loved and was then asked to divide her love amongst his brothers. The woman who the Kauravas tried to disrobe in public and not one of her husbands stood up for her because their loyalty to each other was stronger than their love or empathy for her. It was always about the five of them. She was the outsider, never able to locate her place in their thicketed brotherhood. The wife of men who did not come to see what was left of her after she survived her brutal public humiliation.

Shashi imagines her pain and anger thus,”None of them came to me at the end of that terrible day, the day we will never be able to forget. Not one of them even sent word to me. It was their mother who came to me instead. She said nothing, she did not try to comfort me, or soothe me, either. Nor did she curse Gandhari’s sons or excuse her own. She sat by me and combed out the hair I would not let the maids touch, the hair I had tried to tear out by their roots. Indeed, I would have done it if my women had not restrained me. And then Kunti came and began to comb my hair, long and plentiful then. She went on and on until I could hear the comb singing through my hair. Neither of us spoke, no, not a word. What was the use?”

Shashi wrote a story about Kunti because, “she came out of my feeling that the entire Mahabharata is written by men. This has always been my feeling about the women in the epics. They have been written by men who write about women as they think women are. I don’t think these women are metaphors for anything. They are themselves. Maybe, we can identify with them as we often do with fictional or historical characters.” Shashi sees Kunti as the girl who had to give up her first born and then mourn him after the war had taken everything and everyone away, even the sons who survived it. As the woman who could not forgive herself for destroying Draupadi’s selfhood and yet connected deeply with her.

In her story, Kunti recalls the moment when she had to let Karna go as a baby,”I could still hear the cries of the child, cries that drowned the sounds of the river. I kept hearing them; however far I went from the river, wherever I went, I could still hear the crying. It was only that day, when I went to meet him – and yes, again by the river – a grown man now, and he turned and faced me, his face cold and distant – it was only after that that I stopped hearing the cries. As if the child had died at last. There were so many things I could have said to him that day: I was too young, I was only a child, I did not understand what I was doing, I only did what they told me to do. I could have said all these things, but what was the use? He would not have heard me. We had put a bit of armour by him when we put him in the river. When I met him after all those years, it was as if he was wearing that armour. Nothing I said would have penetrated. My son, I called him, but he never called me `Mother.’ Not once. That bit of armour – no, it did him no good, no good at all.”

And Duryodhana? Says Shashi, “Duryodhana just entered my mind one day and made me write about him. Strange, because I’d never sympathised with him. A rare story that was written in one go.”

And in his last hours, this is how Shashi imagines him, “From being a great and glorious king to a dishonoured and defeated man. Defeated. Dishonoured. As he tasted the words, something happened to him. Thoughts, the like of which had never touched his life, came in. Hesitantly at first, like timid guests. Then, rushing in more boldly, the way brash, familiar visitors do. And it was as if all those things that had seemed so full of sweetness when he had dreamt of them a little while back – pomp, glory, royalty and yes, even, love and loyalty – all these things became misty and unreal. No more than part of a dream he had dreamed, standing here, submerged in the slushy waters of a lake. A dream, whose beauty was flawed by unreality.”

Says Shashi, “I don’t think the epics miss anything. It is we who have made stereotypes of characters and don’t see the human being in the person. I was freeing these characters from their stereotype casing, that’s all.”

And infusing them with us and us with them.

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight. (http://www.flipkart.com/perfect-eight-reema-moudgil-book-9380032870) . More on Story Wallahs. Other books by Unboxed Writers in our Store

In today’s society it is highly immoral for a woman to have 5 husbands, it is highly immoral even to cosider putting your wife at stake in some game. or you can won a woman in some contest. This kalyug is much better than that dwapar yug..

The Mahabharat is a weird kind of a epik in which Krishna is on one side and the whole of his army is on the side of the enemy. In this so called dharma-yuddha, a religious war, all kinds of dubious means, lies n deceits were used. A woman was made to stand before that venerated old sage Bhishma. In the same way deceptions were used to kill dronacharya, karan n duryodhan.

I also wonder how society of her times accepted marrige of Draupati to 5 persons at the same time n did not raise any objections. Polyandry must have prevailed in those times. If it was wrong Kunti wd have changed her instructionsto her sons, but she didnot. Nor did pandave bros. asked their mother to change her order, and even Draupati accepted it without much of a hesitation.