On the day freedom fighters and lifelong friends Ramprasad Bismil and Ashfaq Ullah Khan were hanged, and a few weeks after the death of Shaukat Kaifi, I heard Shabana Azmi on a channel, quoting the famous couplet penned by her father.

On the day freedom fighters and lifelong friends Ramprasad Bismil and Ashfaq Ullah Khan were hanged, and a few weeks after the death of Shaukat Kaifi, I heard Shabana Azmi on a channel, quoting the famous couplet penned by her father.

“आज की रात बहुत गर्म हवा चलती है,

आज की रात न फ़ुटपाथ पे नींद आएगी,

सब उठो, मैं भी उठूं, तुम भी उठो, तुम भी उठो

कोई खिड़की इसी दीवार में खुल जाएगी”

The not so literal translation would be:

“In this unrelenting, cruel night,

sleep won’t come to those who live on the margins..

still, you must rise and so must I

for one day a window will open in these walls at our united cry.”

The lore goes that a young Kaifi, in solidarity with mill workers would bunk with them on streets and this poem Makaan came from one such long summer night under the shadows of a looming concrete jungle.

It is amazing how poetry of activism, hope and resistance is reborn in new tongues and fresh contexts when an emerging generation needs inspiration.

Even in my home town Patiala, a young boy was seen holding a sign emblazoned with Faiz’s ‘Bol ke lab azad hain tere.”

There is a video of detained protestors in Delhi , singing Faiz’s “Hum dekhenge.” Sahir (Woh subah kabhi toh aayegi, tu Hindu banega na Musalman benaga), Neeraj (Taqat watan ki hamse hai), the seminal rebel cry of Sarfaroshi ki tammana (written by Bismil Azimabadi in 1921, and immortalised by Ram Prasad Bismil decades later), Dushyant Kumar (Hui peer parbat ) and Majaz (tu iss anchal ko parcham bana leti to accha tha) are today being quoted on social media, sung on streets and blazing on protest posters.

Just goes to show, it will take more than hate to change the fundamentally unified memory-scape of India.

When a few girls from Jamia Millia Islamia come on air recently to share their experiences post the attack on their institution, one of the first things they conveyed was that a University rooted in the secular ideals of Gandhi and Maulana Azad, has a sacred syncretic ethos that cannot even be broken by brute violence.

This reminded me of how a few days ago, a woman on twitter taunted Farhan Akhtar and asked him to curb his “qaum” from street violence during protests. She obviously has no idea that Akhtar’s grandfather Jaan Nissar Akhar was part of Progressive Writer’s Movement pre and post independence and was commissioned by Jawaharlal Nehru to collate the best Hindustani poetry dating back to 300 years. This was later published as a volume called, “Hindustan Hamara.” To show us the shared poetic impulses of Indian poets regardless of their faiths. To show us just how alike we were and are and always will be.

And those baiting Shabana also have no idea of her lineage either.

For a large part of their golden years, her parents Shaukat and Kaifi Azmi lived in a home called Janaki Kutir. Take that in. This may have also been a place perhaps where Kaifi wrote his poem Doosra Banvas after the demolition of Babri Mazjid in 1992.

The two met and fell in love in an India that was beginning to discover the joy of self determination. Kaifi was part of an anti-imperialistic, progressive writer’s association that was set up in pre-independence India in 1936. It would in post independence India, dream of a seamless social and religious equity and work towards it. Munshi Prem Chand, the master of Hindi and Urdu fiction once even delivered the Presidential Address of a PWA meeting. The collective dream of these writers and thinkers was “tarakki.” Progress and liberation of Indians first from imperialism and then feudalism.

Today the members of this organisation like Kaifi, Sahir Ludhiyanvi, Krishen Chander (whose story Jamun Ka Ped was removed from the ICSE syllabus recently) Ali Sardar Jafri , Amrita Preetam, Saadat Hasan Manto, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Josh Malihabadi, Ismat Chughtai, Makhdoom Mohiuddin, Mulk Raj Anand, Majrooh Sultanpuri, Jaan Nisar Akhtar, Rajinder Singh Bedi and Habib Tanvir would be called urban naxals, hounded and possibly jailed for dreaming that India could be bigger than its religious divides.

Into this ideologically charged world, walked in Shaukat. A young, wide-eyed girl who had fallen in love with Kaifi during a Mushaira . They got married in 1947 and in a way saw the dawn of an emerging India they would both lend their heart and soul to. On the dawn of independence, she and Kaifi and many of their friends went to join the celebratory crowds on Bombay’s roads. There was sloganeering, hope, joy and a sweeping love for the country which was now finally theirs.

Shaukat could just have become an adoring shadow of her brilliant husband but in the one room of a Marxist commune where she found herself building a life with him, there was too much ideological stimulation. She was surrounded by the best writers, poets of that era and so she found herself getting drawn to Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which was ideated following the launch of the Quit India Movement. And given its name by scientist Homi Jahangir Bhabha.

From mounting street plays damning the Bengal famine in 1942, IPTA, became a national movement with idealistic stalwarts like Balraj Sahni, Ritwik Ghatak, Utpal Dutt, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, Salil Chowdhury, and countless others offering fresh perspectives on citizenship, politics and society.

IPTA’s secular, unified voices would also go on to enrich the Hindi film industry’s narratives, lyrics and music in the years to come.

To name a few examples , Khwaja Ahmed Abbas and Raj Kapoor came together to tell stories like Shri 420 and Jagte Raho among many others. Salil Chowdhury wrote Do Beegha Zameen in which Balraj Sahni acted. Ritwik Ghatak wrote Madhumati and went on to become of the greatest film makers in Bengali cinema. Utpal Dutt became a theatre and film icon across languages.

Shaukat worked with the leading theatre lights of her time and raised two kids in a refreshingly modern marriage where parenting was a shared joy and responsibility. Kaifi became a literary giant and in the last years of his life, the miracle worker for his village Mizvan.

The two never had enough money or worldly possessions but they created a legacy that is rich enough to last a few lifetimes. I read some of these stories in Shaukat Kaifi’s biography Yaad ki Rehguzar and then saw it being staged and narrated by Javed Akhtar and Shabana Azmi, many years ago.

The ideological thread binding Shaukat, Kaifi and all the people they knew and worked with, was love. For their country and its people. For them, unlike the tweet happy bullies of today, ‘qaum’ was not defined by religion. It was defined by service. They worked all their lives to make India culturally and socially richer. They chose their nation above every thing else. They and so many others like them were envisioning another freedom movement for India. Another kind of azadi that would free people from hate and divisiveness.

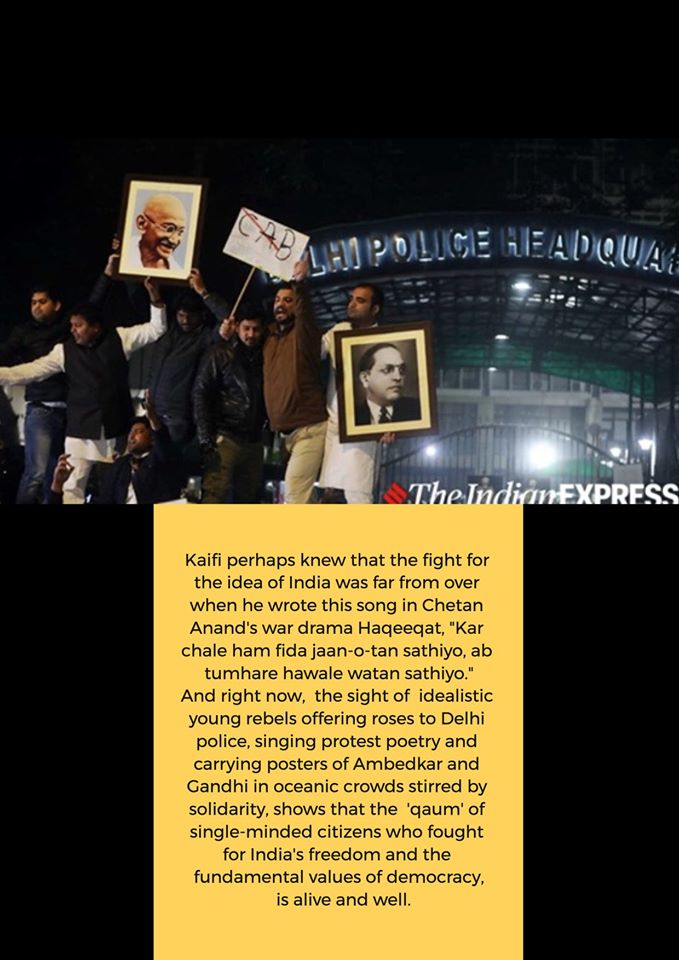

Kaifi perhaps knew that the fight for this azadi was far from over when he wrote this song in Chetan Anand’s war drama Haqeeqat, “Kar chale ham fida jaan-o-tan sathiyo, ab tumhare hawale watan sathiyo.”

And right now, the sight of idealistic young rebels offering roses to Delhi police, singing protest poetry and carrying posters of Ambedkar and Gandhi in oceanic crowds stirred by solidarity, shows that the ‘qaum’ of single-minded citizens who fought for India’s freedom and the idea of India is alive and well.

**Reema is the editor and co-founder of Unboxed Writers, the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, a translator who recently interpreted Dominican poet Josefina Baez’s book Comrade Bliss Ain’t Playing in Hindi, an RJ and an artist who has exhibited her work in India and the US . She won an award for her writing/book from the Public Relations Council of India in association with Bangalore University, has written for a host of national and international magazines since 1994 on cinema, theatre, music, art, architecture and more. She hopes to travel more and to grow more dimensions as a person. And to be restful, and alive in equal measure.