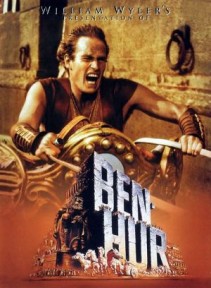

Religion is the saddest of all crutches, more so than Love and Hope. Yet I dare anyone to watch Ben-Hur and not feel a twinge of faith stir in the deepest recesses. By that, of course, I mean an understanding of what Jesus, like Lau Tsu perhaps, stood for.

Made in 1959, this film, like 2004’s The Aviator, grabs you by the throat from the first scene till the last. You forget time, place and circumstance, and are sucked right into the year when the Lord was well on the way to meeting his destiny.

Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston) is a rich Jewish nobleman whose childhood friend Messala is a Roman military commander. Their differing political views with Jewish revolts against Rome proving to be a deal breaker, sow the seeds of the most appalling life changes, and death for one of them.

On a flimsy pretext, Ben-Hur’s family is thrown into prison while he is sold as a slave. His travails are legion, yet it is because of them that he meets Jesus in a chance encounter; the Messiah gives him a drink of water and in that simple act, flicks Ben-Hur’s survival instinct into gear. Ben-Hur goes on to save an important Roman who adopts him and in so doing sets him back on the path of wealth and prestige while he also learns the Roman way of life, like becoming a charioteer.

But history is marching on and Ben-Hur’s mother and sister have become lepers (what a metaphor for modern life, wouldn’t you say?) after having lived in a dank cell for many years. Jesus’ teachings are a red flag to Rome and then Ben-Hur salvages some of his spirit by defeating his old nemesis Messala in the movie’s pivotal and cinematically stunning chariot race (one of the reasons for the movie’s 11 Oscars). He is soon to regain it all.

That is the skeleton of the movie, but it is the magic chemistry between the actors and director William Wyler that sets it apart. There are two scenes that are personal favourites. One is when Ben-Hur returns the favour and gives Jesus a drink of water as the latter goes to meet his brutal death. As he looks up into Ben-Hur’s face, Ben-Hur recognises the man who once helped him and the horror and compassion and realisation that here is something above and beyond himself.

Then there is the scene when Ben-Hur finds his family in the leper colony and the way he moves forward and embraces them while they beg him to stay away, is fearful. You think, He is a better man than I would be in that situation. Yet Ben-Hur is finding within his heart the strength he had once lost in bitterness. What else can he do when facing a man who has met the ultimate betrayal (from humanity he came to save, to literally die for) and found it in him to forgive? In the end, when Ben-Hur listens to Jesus speaking of forgiveness on the cross, he tells his family: “I felt His voice take the sword out of my hand.”

The irony, this being the world we live in, is that dear Charlton went on to become president of the National Rifle Association from 1998 to 2003. You know, believing that everyone in America had the right to own a firearm and blow anybody else’s head off. Not, I think, a very Christian undertaking. But the movie remains unblemished.

Sheba Thayil is a journalist and writer. She was born in Bombay, brought up in Hong Kong, and exiled to Bangalore. While editing, writing and working in varied places like The Economic Times, Gulf Daily News, New Indian Express and Cosmopolitan, it is the movies and books, she says, that have always sustained her.

A slightly off-topic remark here. While it is true that this film was Charlton Heston’s real launching pad as he went on to star in mega-Biblicals, this film was a blockbuster only because of William Wyler. This film also marked the return to big blockbusters in Hollywood, not seen much after the DW Griffith days. Certainly not as box office successes.