It takes more than passion to achieve what Mohan Khokar did. He was like a man possessed, who collected everything that was possible on the subject of Indian dance. Dance aficionados would be familiar with the man who was himself a dancer, dance teacher, scholar and collector but for those who are not, an exhibition that has been curated by Khokar’s son Ashish and is being shown at Delhi’s Visual Arts Gallery is a chance to know all about the archivist and his unique collection.

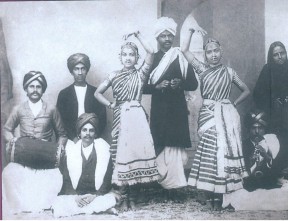

Titled The Mohan Khokar Collection – A Century of Indian Dance 1901-2000, the show exhibits rare samples from Khokar’s sterling repertoire of archival material spanning over 200 years and what was till now locked up in trunks – rare books, photographs, posters, masks, dolls, press clippings, magazines, letters, costumes, statues, sculptures, drawings and paintings – at Ashish’s family house in Chennai. “My father took nearly 200,000 pictures himself,” says Ashish, “and collected 60,000 brochures and 100,000 newspaper clippings. What I have been able to show here is just a small fraction of the collection. It now requires a museum which will enable its preservation and conservation. This is of national treasure value,” says Ashish, also curator of the display which comprises of more than over 200 artefacts.

Ashish’s statement is no exaggeration. One look at the extraordinary, and exhaustive, showcase and you realise its heritage value instantly. A rare photograph of dancer Ram Gopal in his exotic costumes, a 1969 photograph of Madame Menaka, a dancer-choreographer whose real name was Leila Sokhey and who started the first dance school in Bombay, or the picture of legendary dancer Balasaraswati with a seven-year-old Hema Malini who played a minor role in Kuruvanji – these are only few samples that leave you spellbound.

The show has been conceptualised by artist AZ Ranjit who has divided it into different sections – A century of India dance gallery, Dance objects in everyday life gallery, Costume gallery and Nataraja Gallery, the last being the one where you find tangible valuables – like the unique 150-year-old Nataraja painting made out of broken bangles and beads – as well.

Then there are some unique brochures. One is of Tara Choudhury’s Lahore-based dance school, Bharata Natya. The text on the carefully preserved brochure reveals how society at that time used to treat dance and how those who wanted to promote it had to verbalise their very intent. “Indian dancing is the healthiest form of exercise and recreation. It can be learnt, with pleasure and profit by people belonging to all castes and communities. There is nothing improper and objectionable about its study. It is entirely different from the ball-room dancing of the West.”

The exhibition also celebrates the contribution of stalwarts, during a time considered to be the golden era of performing arts in India through images of Udai Shankar, Mrinalini Sarabhai, Shambhu Maharaj, Birju Maharaj, Sitara Devi and Indrani Rahman. Also part of the exhibition are greeting cards, geometry boxes with imagery of Indian classical dancers, gramophone records and stamps on Indian classical dance from Singapore, which according to Ashish came out much later in India.

To prevent these delicate and fragile photographs from damage, Ashish has reproduced these images on PVC flex banners. However, a few originals will be placed alongside. “My father never worried about who would take care of this collection after him,” he says, who has steadfastly added to the collection after his father’s demise in 1999, “he used to tell me that just as he was meant to build it, someone would look after it too. Now it is upto the government to find it a permanent place.”

After this exhibition, maybe his hope will come true.

The exhibition will be on till July 24 at Visual Arts Gallery, India Habitat Centre after which it will travel to USA, France, Italy and several other countries. Dance films will be shown daily between 3 p.m. and 5 p.m.