In Muzaffar Ali’s 1981 master-piece Umrao Jaan, one of the opening scenes featured Ustad Ghulam Mustafa Khan’s voice as it wove sublime magic with a raagmala, Pratham Dhar Dhyan. And there is a young Umrao in the frame, singing along, wrapped coyly in a white silk dupatta and the poetry, or nafasat (delicacy) of another time. That young Umrao was Seema Sathyu, film and theatre doyen M S Sathyu and writer Shama Zaidi’s daughter.

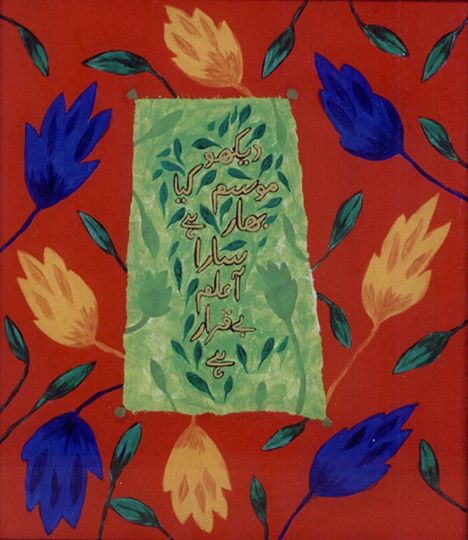

The music and poetry she grew up with have not left her still. She is an artist who paints the soul cries of Ghalib, the sweet cadences of Khusrau, the purity of Sufiana poetry and the world of the spirit that claims every beautiful note, phrase and image in the world without first viewing it through the lens of religion.

The Sathyu home is an experience in itself. It does not display awards, a lifetime of achievements, the swagger of fame.

Without trying hard, it encapsulates everything that the Ganga Jamuni tehzeeb stands for. It is an effortless confluence of faiths and art and life and colour and music from multiple sources, and it is here that Seema lives and paints doorways, arches, ponds, flowers, birds, dreams on paper and canvas. In an interview, she relives her artistic influences and her art.

This passion for Urdu poetry..

Somehow, I fell into it! Earlier in my work though, there was a lot of whimsical, feminine angst, but now the narratives are no longer personal. The works are more abstract and esoteric. I keep returning to Faiz, to Ghalib and the challenge is to come up with imagery that does justice to their poetry. The woman is still there…not so much anatomically but as a flower or as a presence. The artistic shift came within when I discovered Sufiana poetry through the music of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. In Khusrau, I discovered abundant imagery.

And the calligraphy?

Urdu calligraphy was a part of my childhood and it has resurfaced to repeat a sound or a word that may be occupying me at a given point. The structure of the calligraphy is very architectural, very classic, but I make it contemporary.

What is the biggest influence on your work?

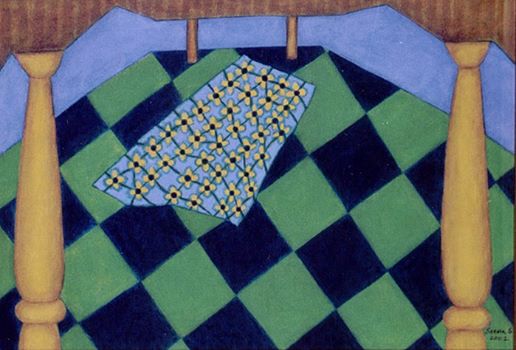

Apart from Urdu poetry? Miniature paintings. Even the colours have acquired a Sufiana sukoon (tranquillity), thehrav (equanimity). And of course, my parents who have worked so extensively with theatre and cinema. My works are very theatrical, ‘staged’ in angles in terms of perspective. As a young girl, I saw a lot of world cinema and saw a lot of films by painters-turned-directors and from them I learnt stillness in motion and the relationship between spaces. My mother has worked with costumes, art design, scripting, and my grandmother Qudsia Zaidi was a playwright. From these two remarkable women, I inherited the love for the written word and traditional textiles and design and all of that has organically seeped in my work. Anjoli Ela Menon’s work with furniture inspired me to paint my doors, reclaim old chairs and paint them. I even apprenticed with her occasionally. I also love quilting so my forthcoming shows will feature that element as well.

Your life and work represents a confluence of something bigger than religion..

The harmony was never forced down our throat. We spoke this language of oneness without ever consciously asking why, how and when this confluence had come together in us. We belong to both the worlds that do not belong to religion, but culture. We live differently even now…untouched by the divisiveness around. The currents of intolerance are deeply disturbing and I feel like a mute spectator. Of course, the ripples of what we are seeing today began 20 years ago. Now it is more structured, to put it bluntly.

Do you think the regimentation of culture can ever succeed?

It is a passing phase…though it may take 20 years to pass! The voice that speaks to and of everyone may get muffled but it will be around. It cannot be lost. Culture is not constant. It shifts, changes but can’t be destroyed. It can’t be muzzled.

Published earlier at http://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/bangalore/Painting-the-Music-of-Confluence/2014/06/09/article2270908.ece1

Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, Bangalore, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, an artist, a former RJ and a mother. She dreams of a cottage of her own that opens to a garden and where she can write more books, paint, listen to music and just be.

with

with

I want to know more about the book.