Some films have a gender. Some don’t. For me, Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather has none. It is just what it is. A movie that you discover at some point in your life and then keep rediscovering. It never ages though you do. I was roughly about three when it was made and discovered Mario Puzo in my uncle’s book shelf during the summer holidays in my teens and was totally shaken by the world of brutality the book sucked me into, the inevitable violence and moments that were just pure drama though morally ambiguous. The remains of Khartoum in Jack Woltz’s bed, Luca Brasi’s death, Michael facing Sollozzo and McClusky in that dimly lit Italian restaurant and the Sicily interlude and the retribution that won’t stop for God or man.

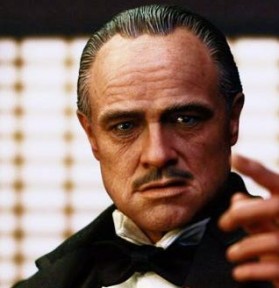

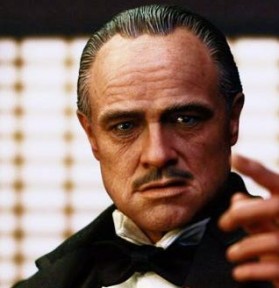

I was’nt able to see the movie till I was in college and that too only when Doordarshan serialised the entire Godfather saga and then suddenly, I discovered Brando. Forty years after the film was made, I am still discovering him. “Before Brando, actors acted, after Brando, they behaved,” so said Johnny Depp once and that really is that. The Godfather as a film brings Mario Puzo’s page turner to life but it also imagines the key characters with such commanding assurance that it is impossible to go back to the book without the film playing in your head, without imagining every single character in the book just as the film fleshes it..Michael will always be Al Pacino and Brando was Godfather.

There could not have been another. A few years back, I ran into Marlon Brando, a brilliant documentary on Zee Studio that captured cinema at its purest, most sublime and subliminal. This was a passionately driven tribute to not just a mercurial, enormously charismatic, controversial man but to his craft. Articulate actors like Depp, Sean Penn, Dennis Hopper, Jane Fonda, Robert Duvall, James Cann, Al Pacino, Edward Norton, Jon Voight, John Travolta and director Martin Scorsese tried to unravel the mystique of a man who regardless of his personal failings created a vocabulary that can only be called Marlonesque.

Few blessed or cursed (depending on how they carry the burden of their gifts) beings can say to the world, “This is how I do it and I will change everything henceforth.” Brando did that because while other acted, he became. Mind, body and soul. You saw an untamed, bristling, almost frighteningly beautiful Brando near a flight of stairs, letting out that unforgettable plea, “Stellllaaaa!,” in A Street Car Named Desire. You saw his rabble rousing Antony in Julius Caesar shutting up the critics who had often accused him of mumbling. You saw him spawning a genre of leather clad, stormy, bike-riding rebels with The Wild One and answering, “ What are you rebelling against?,” with a nonchalant, “Whaddaya got?” You suffered when he was pounded into a bloody pulp in On the Waterfront.

And when he said, “I could have been a contender,” he was our spent soul. When unbeknownst to us, he was coaxed and cajoled into saying, “The Horror..the horror” in Apocalypse Now, he summed up the entire film in one dying gasp. And ofcourse The Godfather. Robert Duvall recalled how Coppola put a cat on Brando’s lap while Vito Corleone is holding court in his study and how in the hands of a lesser actor, the scene would have become about the cat but in Brando’s lap, the cat looked as if she had been there forever. There was as the documentary said, the absence of method in Brando’s method. There was no beginning, or middle or end. There was just one moment. And that moment was life. Not cinema. He was not the bleached perfection of one dimensional purity.

He was not air-brushed. He was no Cary Grant. He was elemental. Sometimes embarrassingly so because before him, no actor had expressed the ache of unfinished business, the loss of promise, the sweep of lust, the immediacy of life and death with a sweat-beaded intensity. It is fashionable to mourn the loss of his physical beauty when he lost interest in Hollywood and spent his time deconstructing his stardom with three marriages, nine children and an inexplicable but heroic decision to refuse the Oscar for his seminal performance of a genial Mafioso whose every facial twitch, jaw stroke and nod became the stuff legends are made of.

Clippings from his interviews, his occasionally reviled commitment to civil rights, his humour, his life, his death, it was all there and in the end, you just felt grateful that though it has been just a few years since Brando passed on, the essence of him still lives in us. Brando was flawed and human and he was destructible. But as we are learning, memories survive everything. It would be too presumptuous to say that Brando outlives his death because we remember him. He lives because, he is unforgettable. And because there will never be another like him. Because we will always go back to The Godfather to learn how legends grow with time while fads fade away.

Dear Ma’m,

I can say without thinking that I have loved every word written in this brilliant piece,a befitting tribute to the actor,the movie.

What can I write,but thank you for this article.