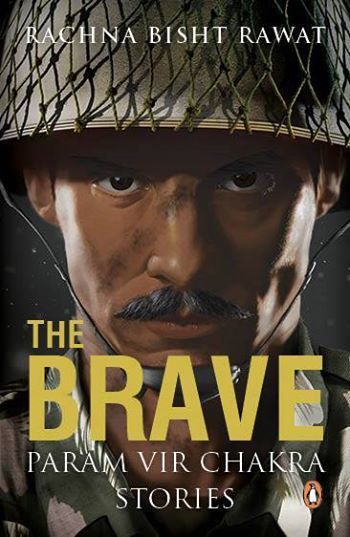

Editorial note: Rachna Bisht Rawat is out with her first book The Brave. Read 21 riveting stories about how India’s highest military honour, Paramveer Chakra was won. Rachna takes us to the heart of war, chronicling the tales of India’s bravest soldiers. Talking to parents, siblings, children and comrades-in-arms to paint the most vivid character-portraits of these men and their conduct in battle, and getting unprecedented access to the Indian Army, Rawat has written the ultimate book on the Param Vir Chakra. We publish here a short excerpt (with the permission of Penguin) based on Captain Gurbachan Singh Salaria, a military war hero, who was awarded the Param Vir Chakra, India’s highest wartime military honour. He did his early schooling at the famous Bangalore Military School. He was commissioned in the 1st Gorkha Rifles (the Maluan Regiment) on 9 June 1957 and died on December 5, 1961 (aged 26) at Elizabethville, Katanga, Congo defending the UN Headquarters from rebels.

Elizabethville, Katanga

5 December 1961, 1.12 p.m.

Two bullets had pierced his neck.The blood was seeping down and soaking his shirt. Right ahead he could see the gendarmerie running away.

Some of his brave and gutsy Gorkhas were still giving chase.

He did not resist when an immense weariness enveloped him. He had lost too much blood. His task had been achieved and he was at peace. Closing his eyes, Capt. Gurbachan Singh Salaria of 3/1 Gorkha Rifles, dropped his rifle and fell, drifting into unconsciousness from which he would never awaken.

Many years earlier, when Salaria had joined the Gorkha

Rifles, he had been told that his regiment’s motto was: It is

better to die than to be a coward: ‘Kafar hunu bhanda marnu

ramro.’

Salaria had lived up to the motto.

Salaria fancied himself a palmist. Before the Congo deployment

in February 1961, he had visited Chotta Shimla for some work

and run into an excise officer, who used to read people’s palms.

Reading Salaria’s hand, the officer told him that there was a

star on his mount of Jupiter, which would bring him great

fame. Salaria took the prediction very seriously and would

often point it out to fellow officers in lighter moments.

Maj Gen RP Singh recalls Salaria showing him his own right hand.

He pointed out the star on his mount of Jupiter.

‘Wait and see, this star will take me to great heights,’ he said. Singh

had leaned over to feel the mount, but only out of politeness. ‘I

just shrugged it off as I never took his knowledge of palmistry

seriously,’ the general recounts. ‘I did not know that his day

of reckoning and attaining fame was just a few days away. Or

that he would never know of this fame since it would come

when he was in his heavenly abode,’ he says quietly.

Instead he just told Salaria that no one could stop anyone

from achieving fame if it was written in their destiny. Soon

after Salaria left after refusing a dinner offer, Singh took out a

copy of Cheiro’s book on palmistry that he had in his suitcase

and read about the star on the mount of Jupiter. ‘These

people are ambitious, fearless and determined in all that they

undertake. They are leaders. They concentrate on whatever

they may be doing at that moment and see no way but their

own,’ said the book.

Gurbachan Singh Salaria was born on 29 November 1935 in

a village called Janwal, near Shakargarh, now in Pakistan. Th e

second of five children, he was a favourite of his grandmother,

who would tie a black thread around his waist to keep the evil

eye away from him. By that time, Adolf Hitler had already

emerged as a dark force and war clouds were looming over

the world.

Gurbachan’s father Munshi Ram was in the Armoured

Corps of the British Indian Army and would move from one

Army cantonment to another, coming home only on annual

or casual leave. When he did come home, it was celebration

time in the family. His favourite food would be cooked, the

house would sparkle and friends and family drop in to listen

to his awe-inspiring tales of faraway places where soldiers

performed great acts of bravery. Little Gurbachan and his

siblings would listen to their father in rapt attention as he sat

smoking his hookah. Quite possibly this is how Gurbachan

was inspired to be courageous.

Gurbachan’s mother Dhan Devi had never been to school

and was completely occupied with her growing children. She

was, however, very particular that her children’s education

did not suffer despite living in a village. Gurbachan would

go to school regularly, but was always more occupied with

games and outdoor activities rather than studying. He was a

good kabaddi player, and continued to be good at sports even

after he cleared the entrance to King George’s Royal Military

College (KGRMC), Bangalore, at 11 years of age. Though he

was initially rejected in the physical exam because his chest was

found to be an inch less than the stipulated measurements, he

was given a month to try again. He took the challenge head

on, drinking one litre of goat’s milk every day and exercising

passionately.

When he went back for his medical, he had managed

to increase his chest by two-and-a-half inches and was

immediately admitted. He joined the college in August 1946

as a cadet. In 1947, he was transferred to KGRMC Jullundur,

which was closer to his village.

When he was in his second year, Gurbachan and a friend

were once bullied and insulted by another cadet. Gurbachan’s

self-respect took a blow but he challenged the bully to a boxing

match the next day. He boxed with such fury that the bully was

knocked out and had to apologize. Th e operation in Congo

was very reminiscent of this incident; where Gurbachan took

on a much bigger and better equipped enemy fighting force

just because he wanted to teach them a lesson in war ethics.

Gurbachan went on to the National Defence Academy

and then the Indian Military Academy. He joined 2/3 Gorkha

Rifl es in July 1954 where because of his cropped hair cut

and upturned moustache he was nicknamed Khan Saheb by

his commanding offi cer. In March 1960, he received orders

transferring him to 3/1 Gorkha Rifles. And that was where

General R.P. Singh, who was then the battalion adjutant,

met him. General Singh found Salaria to be a simple man, spartan

and very careful with money, unlike other young officers,

many of whom had extravagant tastes. In fact, Salaria once

told him, he recalled, that he was sending money home to

finance the education of his younger brother Sukhdev, at

college in Jammu.

Sukhdev is now 75 and lives in Pathankot. He is bedridden

and has lost his sense of balance, but he remembers fondly

how, when he and Gurbachan were little boys—Gurbachan

was older by two years—they would go swimming in the

small stream that ran across their village. ‘We had no worries

then; we would splash around in the stream. What beautiful

days they were. Now Gurbachan is gone and I can’t walk, but

whenever I think of him that is the first memory that streams

into my head,’ says the old man, sinking back into silence.

He has more memories to recount but his strength fails him.

Rachna Bisht-Rawat is an author and journalist, a mom and the gypsy wife to an Army officer whose work takes the Rawats across the length and width of India. She blogs at http://www.rachnabisht.com/.

Rachna is a 2005 Harry Brittain Fellow, and has won the Commonwealth Press Quarterly’s Rolls Royce Award in 2006. Rachna’s first short story,Munni Mausi, was a winner in the 2008-2009 Commonwealth Short Story Competition.

Order her book here http://www.flipkart.com/the-brave-english/p/itmdzsmvpazuhnjn