A few days before Om Puri passed away, I shuddered past a YouTube video (obviously fake) that speculated if he had converted to Islam. No prizes at all for guessing why the video had been created. To fan the hate that his support for Pakistani artists had kindled amid patriots whose claim to nationalism is trashing a life time of contribution to the arts by a man who was not just an actor but part of the weakening mortar that has built a composite idea of India. A man who worked in cinemas across cultures, played characters that spoke for the most oppressed, shed light on the most entitled, caricatured power mongers and caressed humanity with a creased smile.

**

He was an international treasure and yet he was hounded for his unpopular support to the arts at a time when politics has vitiated everything around us. He was hounded just as Sadashiv Amrapurkar was when in March 2013, he protested water waste during Holi near his residence in Mumbai. Just as AK Hangal (incidentally a freedom fighter) suffered terrifying political calumny in 1993 when he applied for visa to visit his birthplace in Pakistan and attended the Pakistan day celebrations at the consulate in Mumbai. He was labelled a traitor by Shiv Sena, a call to boycott his films was made, his effigies were burnt and his scenes were deleted from many films.

**

And now Om Puri is gone. And no, not many of us spoke up for him while he lived. Though there is a video on YouTube titled, “Om Puri’s wife crying beside his body in Cooper hospital.” This is what has become of us. Every person of some consequence, living or dead must be turned into a click bait.

**

And I am thinking of a favourite Om Puri moment that to me sums up his life. A life where he fought to be true to his beliefs at great cost to himself. In Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala, he played Abu Mian who with his creaky bones, henna tinted beard and kohl lined eyes, watches over the women who work in a small masala factory. When there is a sudden unexpected siege and Sonbai (Smita Patil) takes refuge in the factory to escape from the Subedar (Naseeruddin Shah), he is the only man in the village who dares to face the consequences of standing up for what is right with raw courage.

**

In this role as was the case in most of his cinematic outings, you never saw the effort or the brush strokes of a performance. In Abu Mian, you just saw a character with immense dignity who turns cinema into a lived experience. His slow, deliberate movements as he loads his rifle , his steady gaze as he aims at the pack of baying soldiers outside is a masterclass in understatement.

**

Watch that moment in 1985’s undersung Govind Nihalani masterpiece Aaghat where he smiles indulgently at Loveleen Mishra and instantly conveys in a micro second, the extent of warmth and affection he feels for her. Or the seething silence of his Lahanya Bhiku in Nihalini’s Aakrosh (1980) which like a vortex sucks us into the horrors he has seen, the screams he has heard, the physical and spiritual violence he has endured. Or his Dukhi in Sadgati (I981) whose utter destitution along with Smita Patil’s cathartic outcry in the end connects you to a pain you have never acknowledged because you have never felt it.

**

Or his Nahari in Gandhi who thrusts a roti in front of a fasting Gandhi and screams, “Khao!” Or his Nathu in 1988’s Tamas (Nihalani again) whose gaunt, famished face and haunted eyes show us the horrors of Partition, and the guilt of a man who unknowingly has become a pawn to trigger a communal earthquake.

**

In Party (1984), another Nihalani film, his is the voice of honesty and truth at a social gathering full of poseurs and even though the film’s most stunning moment comes when Naseer saab’s visceral cry in the end brings alive a rebel poet’s agony after his tongue has been cut off, it is Puri who with his calm manner reveals the hypocrisy of those around and the irony of a country where bloody tribal oppression and intellectual discussion in radiant drawing rooms co-exist without ever intersecting each other.

**

And yet there was that hilarity that he could trigger with just that one moment in Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro where he mistakes a coffin lying in the middle of a road for a Baby Austin and proceeds to change its “tyres.” His cameos in Nihalani’s Vijeta and in Sai Paranjpay’s Sparsh where he plays a blind teacher devastated by his wife’s death also show how little screen time he needed to get your attention and keep it. And even when he was working with international icons like Helen Mirren in The Hundred Foot Journey, he never became conscious of their stature because he had earned his space in the narrative not by chance or opportunism but with uncompromising diligence and pure brilliance.

**

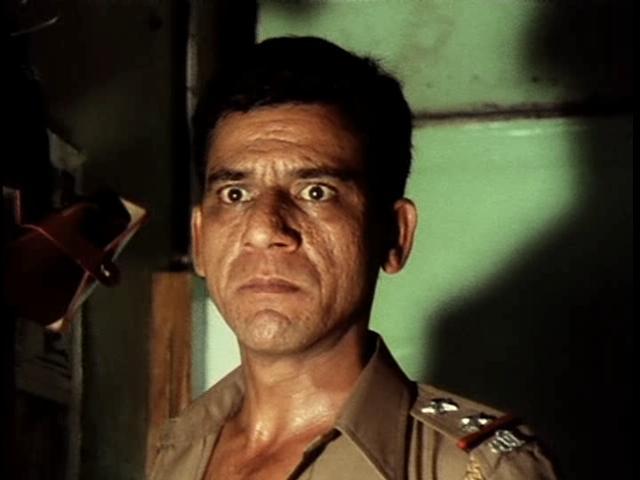

It is also ironical that his path-breaking Anant Velankar in Ardh Satya (Nihalani yet again) was first offered to Amitabh Bachchan because somehow a rebellious, idealistic cop could not possibly have been played by anyone else! And yet, his clenched yet feral aggression and taut, leashed body is the keynote of a film where his confrontational scenes with Sadashiv Amrapurkar should be a part of every acting school curriculum. Even in a commercial pot boiler like Ghayal, it is his cop you watch for a reality check.

**

And that was what he made us do in film after film, performance after performance.

A reality check. He connected us to the unspeakable agony and the million emotions and truths embedded in the human condition with absolute conviction and honesty. He made the invisible visible to us and showed us the beauty of diversity and how nothing divides us except perception. Like Papa Kadam in A Hundred Foot Journey, he made us believe that every distance can be spanned if you take the first step.Truly sad that he had to suffer so much isolation and negativity and go this way. Alone and unappreciated.

**