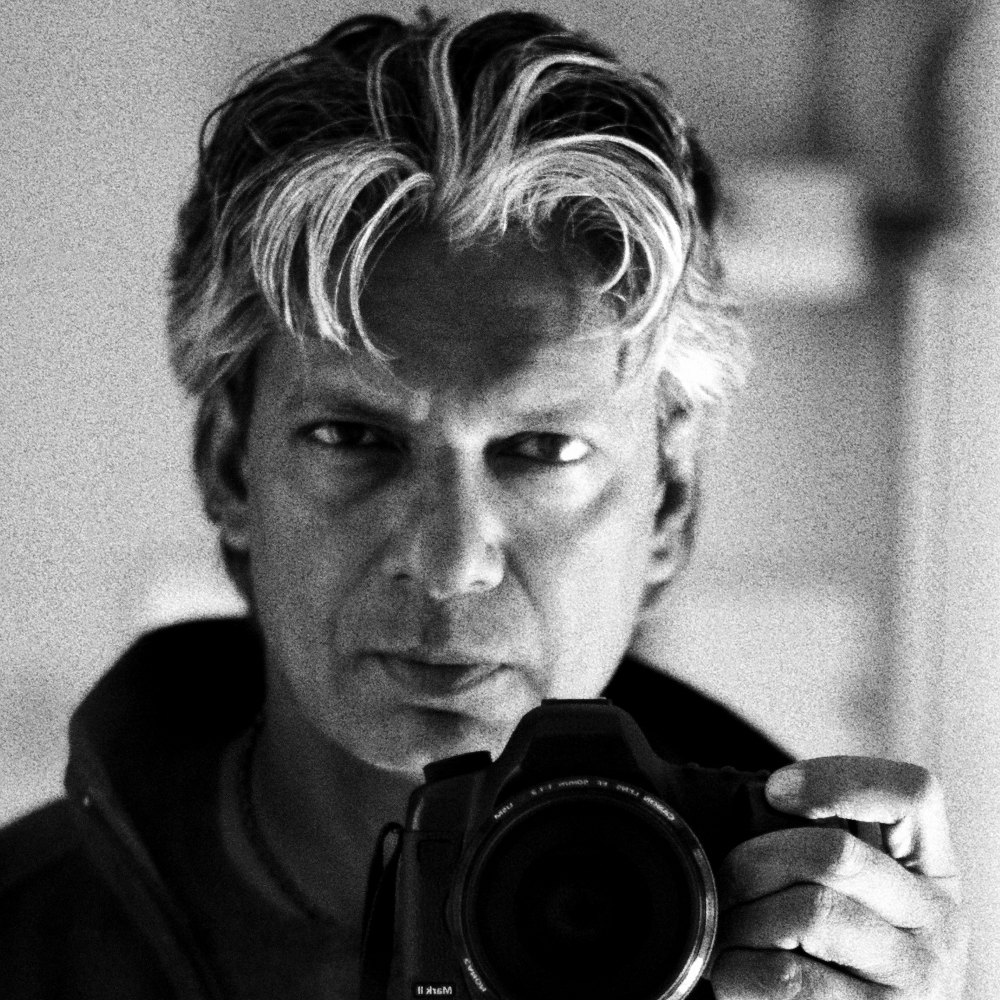

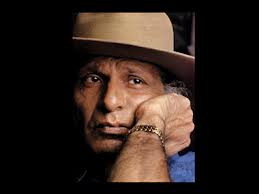

What does a cinematographer or a photographer do that we can’t? Well, he reinterprets the world through his gaze, recreates it, focusses on moments that say, “Watch this. This is important. Beautiful. Relevant,” bleaches a frame of colour or suffuses it with rainbows. Catches butterflies. Dewdrops. Rain streaks across a window pane. Faces with all their truth. Their pain and their beauty and their light and their shadows. Sweat beaded bodies and sweeping panoramic shots of cities and depths of wilderness. He sees what we can’t. He is the God of detail. Of structure. Balance. Harmony. And this week, two such Gods were taken away from us. Prabuddha Dasgupta and Ashok Mehta. Both masters of their worlds. Their craft. Both with unassailable artistic integrity. I met Prabuddha Dasgupta many years ago when he had just put together a book for street children called If I Were Rain. The book was a heartbreaking yet uplifting account of the lives of millions of kids who live, grow up and sometimes die on our streets, unnoticed, unloved, unprotected.

Kids who scavenge for food in bins, get beaten up by policemen, are sexually abused, fall into addictions and prostitution rackets, have no support systems except the friends they make on the streets, most of them as vulnerable as they are. They sleep on pavements, in gutter pipes and yet dream of becoming actors and doctors and policemen. The joy they have in their shining eyes, their famished bodies as they dance to Hindi film songs, save money to watch films. The book had pictures and quotes and data that ripped layers of apathy from anyone who dared to open it. It was an unusual artistic gesture coming from someone who was and is India’s finest fashion photographer. Someone who turned the human body into a haiku, a poem, a powerful statement of sensuality, power and restraint. But speaking to him gave me a glimpse into the kind of a man he really was.

Even though he worked with it, he never bought into glamour. It was nothing but the raw material for art. It was not reality. Reality was what he saw and was affected by. He spoke passionately and long about just how many kids out there were waiting to be rescued, loved, healed in a country that had no time for them. A country that did not notice them because they did not form a vote bank or so did not figure in any election manifesto. We do not have a national policy about street children, do we? They have been left to fend for themselves and warned Prabuddha, they would grow up watching kids blowing up thousands in malls on food they cannot finish and one day they will want the same things and if they cannot have them, they will steal, rob or even kill. We are ignoring an entire generation that will grow up resenting the other half and one day the fence between the haves and the have nots will be smashed and the consequences will not be pretty, he said. I still remember his contained anger and his commitment to making a difference to atleast a few lives.

Both Dasgupta and Mehta were lone rangers, driven by an inner flame to create a new visual language that had not been spoken or heard before. We will never see the world through their gaze again. What a loss.