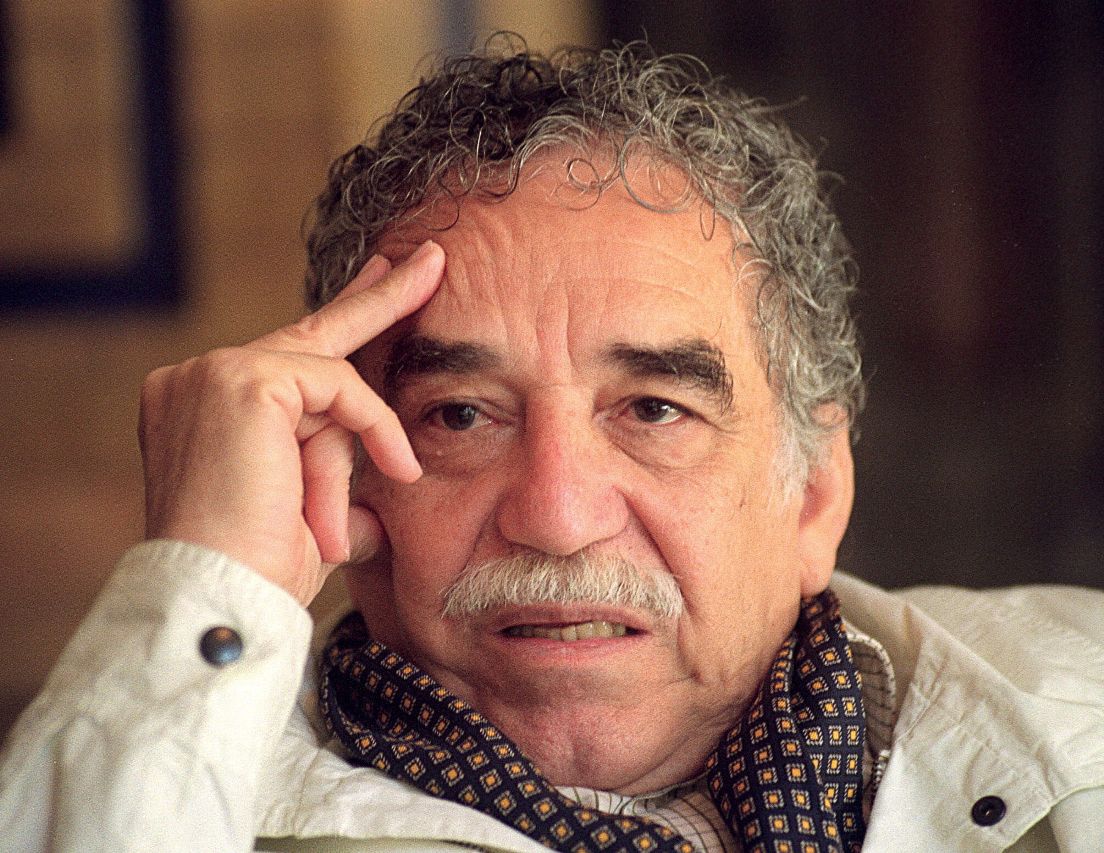

The immediacy of pain and loss . the kind that One Hundred Years of Solitude narrates is not so much as fiction, as it is life. The life we invest hope and love in when we wake up every morning, watch a day go by, sometimes lose a part of us and occasionally find a missing piece.

And so Gabriel García Márquez wrote. “If I knew that today would be the last time I’d see you, I would hug you tight and pray the Lord be the keeper of your soul. If I knew that this would be the last time you pass through this door, I’d embrace you, kiss you, and call you back for one more. If I knew that this would be the last time I would hear your voice, I’d take hold of each word to be able to hear it over and over again. If I knew this is the last time I see you, I’d tell you I love you, and would not just assume foolishly you know it already.”

He himself said once that though critics credited him with an irrepressible imagination, everything he wrote was rooted in reality. In pain and suffering and what you do with it when you become a writer. You polish every hurt and make it shine, and turn reality into magic.

He wrote in Love in the Time of Cholera, “I would not have traded the delights of my suffering for anything in the world” and that is the tap root of all creativity. If there is no pain, there is no fuel to smash through it and so Marquez’s books though bare-boned in their understanding of the messy business of life, also uplifted and healed. There was humour, a responsiveness to the visible and the imagined, the latent and the subliminal.

He never complicated the process of writing, letting critics deconstruct his ‘style’ because he believed his writing stemmed from the need to react to life and to interpret it.

And to sometimes go beyond it as when an ordinary act of hanging laundry in One Hundred Years of Solitude takes a character beyond life and death in a spectacularly dramatic flourish. What he did as a writer most competently was to expand the meaning of reality and to get his readers to do a double-take as they look at life and its endless possibilities. Like Ghalib, he too had a thing for solitude, isolation and pulsing letters and what they do to connect people over space and time. “All human beings have three lives: public, private, and secret, ” he wrote and in his books, all these were explored.

Unlike a lot of lyrical writers though, his grasp over political reality was unerring. His human stories were always contextualised in a bigger picture of social and political complications. His writing had for want of a better phrase, the compositional layers of the earth with a few seismic shocks thrown in. He was lucid, complex, playful and profound and that a Colombian writer went beyond the limitations imposed by language to tell universal narratives, says a lot about what we lost with his death. Another one of those rare story tellers who belong to everyone..

Even to the superficial characters in a romantic comedy like Serendipity. Characters who pin their hope to meet some day on a copy of Love in the Time of Cholera (2001). Even to young adults who only discovered him through his indulgent support of fellow Colombian Shakira. For a Noble Laureate, Gabriel García Márquez had a lightness of being. He is possibly rewriting the story of the after world with a smile and a frown even as we mourn him in this one.

**

This story was carried earlier in The New Indian Express Bangalore (http://www.newindianexpress.com/cities/bangalore/Gabriel-Garc%C3%ADa-Marquez-and-the-Immediacy-of-Living/2014/04/22/article2181440.ece1)

**

Reema Moudgil works for The New Indian Express, Bangalore, is the author of Perfect Eight, the editor of Chicken Soup for the Soul-Indian Women, an artist, a former RJ and a mother. She dreams of a cottage of her own that opens to a garden and where she can write more books, paint, listen to music and just be silent with her cats.

with

with