Shyam Benegal’s cinema never loses the plot in trying to project itself as a breakaway, alternate idea. His films never preen and say, “Let me show you something you have never seen before,” even though his cinema in the 70s was quietly, unobtrusively radical both in content and in form. He has always had a social conscience but the anger, empathy and despair in films like Mandi, Nishant and Ankur never overwhelm the human story. Benegal never ever intrudes in his narrative, he never projects his ego in his work. His films belong to his protagonists, not to him.

His presence is unmistakable only in the subtle aesthetics of his cinematic universe. In the research he invests in the detailing of his backdrops. In the way his characters dress, speak, inhabit their worlds as if they have never known any other. The bungalows two warring business families live in Kaliyug do not smell of Plaster-of-Paris or show off ornate sofa sets we have come to expect from our celluloid aristocrats. They exude hushed affluence, have priceless art on the walls, and a certain assurance that comes with lived-in, old money.

Observe the havelis in Junoon, the exquisite fabrics Muslim women dress in, the note perfect English costumes, the contrast between two clashing civilisations in the cruel, bloody months of 1857. The natural inflections in dialogue, the seamless way multiple stories come together and culminate in an inevitable end.

Benegal is not a man of flourishes but there is a sense of theatre in his work. He knows what moments need to be underscored and what needs to fade away. His characters speak, pause, connect and detach in ways that are more than life and less than melodrama.

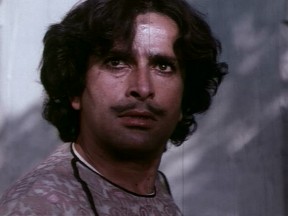

Someday I would like to write a book on Benegal’s work but this piece is about one of my all time favourite films, Junoon. Based on Ruskin Bond’s A Flight of Pigeons, the film pits the sweeping fire of the 1857 sepoy mutiny against the all consuming passion of a pathan Javed Khan (Shashi Kapoor) for a young English girl Ruth Labadoor (Nafisa Ali). The film has almost miraculous casting. Shashi Kapoor is perfection as Javed with his kohl lined eyes, a swagger that speaks of generations of inbred authority in an arrogant, long lined body. Exuding unspoken, tortured passion from every pore, we see him first like a ghostly shadow outside Ruth’s genteel English home, trying to catch a glimpse of her.

Ruth is ofcourse Nafisa Ali in a performance that travels from candle lit innocence to horror when her father along with many others is hacked to death in a church by sepoy mutineers led by a fiery Sarfaraz Khan (Naseeruddin shah). Nafisa as Ruth is a master stroke because she is everything a trained actor would not have been.

She is totally unaware of the camera, has untutored, unaffected innocence in her sunlit eyes. She has the awkwardness of a teenager who is just learning to inhabit her body and the face of a Botticelli angel that reflects like a clear, unblemished pond, every cloud, every rain drop, every passing breeze. Her interactions with Javed are mostly relegated to long glances. At first she is afraid of him. She has been uprooted from the life she knew and has been forced by Javed to live in his home with her mother and grandmother. She sees him as a dark predator who will pounce on her and devour her. And yet, there is a distance between them that he never breaches even though at nights, he is drawn to where she sleeps and she sometimes sees him, standing outside her room, gazing at her in wordless desperation.

He is a curious mixture of male chauvinism and chivalry. Ruthlessly dismissive of his wife Firdaus (Shabana Azmi) who he will accord the right to run his household, feed his pigeons, warm his hukkah and his bed occasionally when he is sexually frustrated, but will not extend his love and respect to because she does not stir his body and soul like Ruth does. And is not capable of giving him an heir.

He ruthlessly kidnaps the Labadoor women, stubbornly proposes marriage to Ruth but never really forces his point and instead waits for Ruth’s mother to give in. He says stubbornly, “Mujhe na sunne ke aadat nahin hai.” But falls into helpless silence when his silver tongued aunt (Sushma Seth) retorts, “Na sunne ki aadat nahin toh na kehne ki bhi toh aadat nahin hai.”

There is the magnificent Jennifer Kendell playing Ruth’s mother Mariam Labadoor, who can douse Javed’s bravado with just a cold glance and spar with him with crisp one liners as he tries to break her steely spirit. A scene that brilliantly sketches the strength of her character is when she watches an intruder stealing into a courtyard at night and then takes a knife out and stabs him to death before he can hurt her or her daughter.

She is an absorbing contradiction. She is an Anglo-Indian woman and the widow of an English officer. She understands Urdu and speaks it because her mother came from a Muslim family. But she has an unmistakable reserve that is not Indian and yet a warmth that bonds her with those who show her kindness in difficulty.

There is a beautiful scene where Ruth, Mariam and her old mother (a spunky Ismat Chughtai) have been invited to spend some time with Javed’s aunt (Sushma Seth) and her lovely daughter-in-law (Deepti Naval). They all are spending a day at a mango orchard during monsoon and here, the women form an inland of kinship that is cut off from the violence their men have suffered or are inflicting upon each other.

They sing songs of their culture and there is this almost lyrical shot of Ruth on a swing as it takes her to and fro in a moment stolen out of fear, loss and tragedy while Mariam sings of love and domesticity.

Once back in Javed’s house, Mariam won’t budge and won’t let Javed marry Ruth because he is a Muslim, because he is already married, because she is mourning her husband but when she runs out of excuses, it boils down to the mutiny and so she plays her last card. If the mutineers win over Delhi, Javed can have Ruth.

Ruth, in the meanwhile is a silent witness to this game of dice between her mother and Javed but something within her has begun to shift. She watches Javed tenderly taking care of his brood of pigeons and grows less afraid of him. The two often steal glances at each other during meals. Even during the late night funeral of Ruth’s grandmother, Javed can’t tear his eyes off her face. Ruth’s demeanour goes through a subtle change. She grows more and more relaxed in her skin, in Indian clothes, going to the extent of dressing up as a young begum, provoking Mariam to exclaim, “You look like a nautch girl!”

Once when she is apart from the home and the man she has come to feel something for, Mariam catches her looking wistfully at pigeons in the sky and knows with sudden clarity that she will have to protect Ruth not just from Javed but from herself.

Every cameo in the film is outstanding, be it Pearl Padamsee as the foul mouthed critic of all things white or Kulbhushan Kharbanda as the Hindu trader who risks his life to save the Labadoor women or the fiercely livid Naseerudin Shah who shames Javed for his self indulgent junoon for pigeons and Ruth with a bitter cry of “Javed Bhai, hum Dilli haar gaye hain!”

Lighting up the film like a painting is the intuitive gaze of cinematographer Govind Nihalani. And the haunting music by the tragically undersung Vanraj Bhatia with gems like, “Ishq ne todi sar pe qayamat,’ (Rafi) ‘Aaaj rang hai’ (Jameel Ahmed) and ‘Ghir aayi kaari ghata matwari’ (Asha Bhonsle).

In the end, as the English brutally suppress the mutiny, leaving behind a trail of villages in flames and dead Indian soldiers hanging from trees, Javed’s family flees the haveli for a safer town. Firdaus sees Javed looking for her in the melee and is momentarily elated but is devastated when she realises he has come back not for her but for Ruth.

Ruth and Mariam (the grandmother is no more) are in the church where it all began, waiting for English soldiers to come their way when Javed pounds the door, asking to be let in. To be allowed to see Ruth one last time.

Mariam refuses and asks him to leave. Defeated, Javed is about to leave when the door opens and Ruth emerges, to call him by his name for the first and last time.

They look at each other for a heartstopping instant and then he is gone on the wings of a wistful Khusro poem.

I love this film because it is Benegal’s take on the kind of love, we have never really seen in Hindi films. In our overtly verbose, singing dancing cinema, love is almost a public ritual, not a personal compulsion. But here, in this film, it is almost wordless and yet heavy with such intensity that you flinch because never before, and never again will you see a naked soul in such agony.

Kapoor is absolutely gorgeous not just as a man in his prime but as an actor who seems to be bursting at his seams to shed his limits as an actor and to burn himself into the soul of a character he has never played before. And this is one of the many gems that Shashi Kapoor’s production company Film Valas produced to not much commercial success but great critical acclaim.

This is a film that will never grow old. It is a masterful, page by page illustration of a period that Ketan Mehta tried to capture in Mangal Pandey but botched miserably but most importantly, it is a story that never fails to stir, move, uplift because it is about the best and the worst in us. And because it speaks of a love that is human, of flesh and blood and yet somehow sublime like a sunkissed cloud.

Reema Moudgil is the author of Perfect Eight (http://www.flipkart.com/b/books/perfect-eight-reema-moudgil-book-9380032870?affid=unboxedwri )

This story was carried in her column in http://tlfmagazine.com/

lovely film.

good article