Is that a horse blowing its own trumpet or is it a donkey carrying the load of an entire household on its feeble shoulders? Why is a globe hanging upside down tied up with slippers, books, petrol cans, water bottles and a mattress too? The rabbit certainly doesn’t seem so ‘hare-brained’ compared to the ‘empty-headed’ man in the same picture! The magic of Manjunath Kamath’s paintings is that you can create as many stories out of them as you like, smiling all the time at the cleverness of his collages.

If Manjunath Kamath had not been an artist, he could have easily found his calling in being a comedian. Making people laugh comes easy to the Delhi-based Mangalorean who is preparing to have his first solo show at Mumbai’s Sakshi Gallery starting April 1.

Kamath’s visual vocabulary, in the past two decades of his art practice, has been much the same – his large scale ‘humanscapes’ have always been colour intensive works that are an eclectic mix of fantasy and realism. Recognised as a visual story teller – in one of his most sought after digital work titled Paneer Pizza, Kamath had used tantalising images of superheroes, ascetics and animals juxtaposed with symbols of modern advertising – he says he finds images from his immediate surroundings. Just as well, for these symbols of urban pomposity create a visual pun that is so easy to enjoy.

While Kamath has found huge success with his digital prints – one hangs at the Kiran Nadar Museum in Delhi – in the current show titled Collective Nouns, Kamath always underlines the deeper sense of philosophy, poetry and provincial micro situations of life in order to elevate and transcend his works from just being framed contexts of laughter.

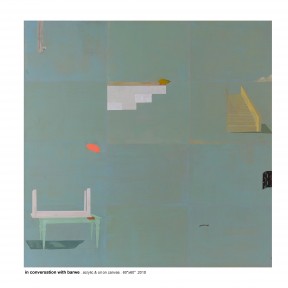

In an acrylic and oil on canvas titled When I said God is dead, Kamath asks the quintessential question of whether God exists, but in a manner that leaves room for both the believer and the atheist to arrive at their own conclusion. Far more minimal in imagery and darker in its treatment this time, in all of Kamath’s paintings – he has moved away from his favourite digital prints – the real meets the unreal. In a work titled In conversation with Barwe, Kamath creates an abstraction of a dialogue with symbolist Prabhakar Barwe, through upturned tables, door latches and staircases leading to nowhere.

“During the past one year I have been reading quite eclectically. I read a lot of Kannada literature, philosophy and poetry. I read newspaper columns, observed people and then came a time when I felt that even the inanimate objects around me were gaining life and momentum. So it was like quoting from a big book of life. In most of my works in this show you would see quote-unquote signs, speech balloons and blurbs not only as visual embellishments but also as strong metaphors,” he says.

Incidents and moments from the every day life have always inspired Kamath. He talks about a museum visit where the broken trump of a Ganesha idol gave him the idea for one his best-known works so far. Titled Looking for evidence, the 6×6 feet canvas had a donkey captured inside a glass box with a stone lying near the animal’s feet. “Historians would have interpreted even that small stone, someone probably threw at the donkey, as a historical artefact…that’s how our history changes based on what our perception of reality is!” According to Manju, as he is fondly called by friends, history has its own movement and “an artist’s vision lies in finding out the dynamics of history.”

However, combining history with humour does not make Kamath’s works just comical pieces. Instead, they offer a world wisdom that is sometimes lacking even in more traditional art. For instance, in one of his fibre glass sculptural pieces in the show titled I forgot what you said last night, Kamath uses headless Kamasutra figures to hold up an empty blurb. Words are not needed here – it could be the story of any lover.

“I have dabbled in all sorts of mediums, including video art. I get bored easily with one style,” says the artist whose canvases, however big they may be, are sparsely habited and the vast flat surfaces look like an undefined area left to be defined and determined by various historical processes. “The images that I build in these flat surfaces are just clues for interpretations. They could be the remnants of a deconstructive process,” says the artist.

Laughing at himself (“I never thought I could make a living out of art”) and others around him, Kamath’s forte ultimately lies in creating fantasies out of the ordinary.