It’s 22 years almost to the day now and no one remembers him: The second person who immolated himself following the VP Singh government’s decision to implement the Mandal Commission recommendations. Surinder Singh Chauhan perished, unlike Rajeev Goswami (who died in 2004), pictures of whose burning body appeared in several papers and made him a symbol of the anti-Mandal protests.

The protests shaped a different kind of awakening for many, including me. Some months ago, soon after Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress government had extended voting rights to include the 18+, I had walked with my father to the government school in Netaji nagar and exercised my franchise for the first time, all in favour of LK Advani. My new somewhat naïve political awareness, then wanted to give the anti Congress opposition a chance. Bofors had corrupted and here were all these incorruptible men, or so I thought, who would do better. And yet, as anti-Mandal protests reached a peak some months later, LK Advani, boosted by this victory and others, victories that arguably became his via myriad convoluted decisions like mine, became a prime figure on television, as he led his chariot around the country calling for a Ram temple.

But this was still some time away. August was a new term in university that never began. Instead it was a month of strange political twists; Machiavellian decision making that included the Mandal decision, and also the angry street protests that followed it. But in our government colony drawing rooms, this anger was muted. To my father and others like him, it was largely a political decision, taken by VP Singh to go one up on his opponents. We wondered in turn about thousands of students like ourselves now affected by the decision. Suddenly things that hadn’t mattered before like people’s surnames took on a greater importance, and appeared in a totally new light, no matter that the Mandal decision implemented then would affect only a few hundred seats. The Civil Service exams were in any case tough exams and people failed time and again, competition among the best defined it. But now we only competed to show off our anger. We marched as part of candle-lit processions, enforcing blackouts in every flat.

In one house, on the eighth floor, someone didn’t oblige, and we, a small increasingly restive, growingly raucous crowd, gathered below, raising slogans, shouting in our righteous anger, demanding his compliance. Nothing happened, not even a curtain fluttered. Finally, it was we who gave up, shouting up one last time that he must be one of ‘them’.

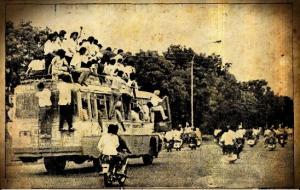

A somewhat confused freedom unfolded the next few days. Classes at university could be called off arbitrarily, and so a friend and I watched from our vantage point at North Block, that housed several important government departments, demonstrations near the India Gate. The irony of our position only compounded the turmoil we felt in ourselves about our futures, made suddenly uncertain by the Mandal decision. What heartened was the news of protests elsewhere, of disparate groups of people; students and government employees. In the mornings, some of us still dutifully waited for the university special, the bus servicing university students run by the Delhi Transport Corporation. When it didn’t arrive on time, as it usually did those days, some of the ‘seniors’, tall, rugged looking, some already in hoodies to keep away that early morning chill, that Delhi begins wearing late September, fanned out across the Moti Bagh crossing to commandeer a passing bus.

We filed in, finding a seat anywhere while the senior boys sat on the dashboard, to ensure that the bus diverted from its usual route headed straight north to the campus. On the way, as we passed flower filled embassy gardens and the wide history witnessing avenues in the city’s heart, they sang haunting old Kishore Kumar songs.

In a few weeks’ again, these protests would die out. The last term in college would begin and only the boy who had led others in commandeering buses, would loll under trees, reading his guides or kunjis, late autumn leaves falling around him, the rest of us filed back to class. Every class would soon tell the same story. Some of us would indeed prepare for the Civil Services, others would take the management exams, and a handful would go on to do research.

In another year or so, with a new government in power, a series of liberalization measures would be announced. India, we read then and later, had been ‘forced’ to open up, while in other ways it seemed, it was closing up into reserved, ever enclosing circles. I moved onto business school too, but dichotomies of those years remain. The years since have seen a wobbly multiply contested liberalization, while reservations for the most part arguably makes up an uneasy, unquestioned political word. More than this, debate on these issues remains half-hearted, or else has become totally redundant. If interests are in any way infringed, anger in the streets will do, and this now wears the same colour like our repeated parliamentary adjournments. It is as if this closeting of ourselves in certain obsessive self-interested ways has also conscripted an atrophy of our political awareness.

PS – Surinder Singh Chauhan died on 24th September 1990.

Anu Kumar’s most recent novel for older readers, ‘It Takes a Murder’ ( http://www.hachetteindia.com/TitleDetails.aspx?titleId=32055) releases this month and is published by Hachette India. More details of this book and her other books and writings are at anukumar.org

we pay tribute to surinder singh chouhan & thousand of other youths who sacrifice their life protesting against mandal commission, on 24sept. 2013 at press club, JAMMU.